On Tuesday, during a phone conversation with Vietnamese President Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Japan’s Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide said that his government “strongly opposes” China’s growing assertiveness in the maritime domain.

As per the Japanese Foreign Ministry, Suga repeated to Phuc his earlier conviction that Japan and Vietnam were important partners in Tokyo’s efforts to realize a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” He added that the Japanese government has particular concerns over China’s “unilateral attempts to change the status quo in the East and South China seas,” including its recent introduction of a law allowing the Chinese Coast Guard to use weapons against ships it views as intruding into its territory.

During the talks, Suga also pledged to help Vietnam set up a $1.8 million cold chain storage and distribution network for COVID-19 vaccines, and promised to provide Vietnam with marine vessels for research purposes. Japan will also open a consulate in the central city of Da Nang in 2022, Suga said.

For his own part, Phuc told Suga that Vietnam “always considers Japan as a strategic, long-term and leading important partner,” according to a paraphrase in Vietnamese state media.

Suga’s 20-minute call clarified and sharpened the comments made during an April 28 call between newly appointed Vietnamese Foreign Minister Bui Thanh Son and his Japanese counterpart Motegi Toshimitsu. As well as workaday concerns such as COVID-19 recovery and trade and investment, the two foreign ministers also “exchanged views on international and regional matters of shared concern, including East Sea issues.”

The East Sea is Vietnam’s official designation for the South China Sea, where it, along with three other Southeast Asian nations, is contesting China’s expansive claims to nearly the entire waterway.

Since taking office in September, Suga has continued his predecessor Abe Shinzo’s push to deepen Japan’s relations with the nations of Southeast Asia, in large part to check China’s growing influence in the region. Few Southeast Asian partners are as important as Vietnam, a country that shares Japan’s close economic and cultural ties to China but remains similarly wary of its growing power and belligerence.

In particular, the two nations are both facing the sharp edge of China’s rapid maritime modernization, dueling with Beijing over parts of the the East and South China seas.

During Abe’s eight years in power, relations between Japan and Vietnam boomed on the back of increased trade and Japanese backing for large-scale infrastructure development, including highways, bridges, and a metro system in the southern metropolis of Ho Chi Minh City. In 2014, the two countries announced an “extensive strategic partnership,” and security ties have also deepened apace.

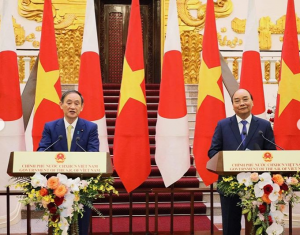

This trajectory has continued under Suga. In October, the Japanese leader visited Vietnam on his maiden overseas trip, during which he met with Phuc (then Vietnam’s prime minister) and signed an agreement allowing his government to export defense equipment and technology to Vietnam. Speaking to reporters after talks with Phuc in Hanoi, Suga described Vietnam as a “cornerstone” of efforts to realize a free and open Indo-Pacific and vowed Japan’s continued contribution to “peace and prosperity in the region.” (The trip also took him to Indonesia, another of Tokyo’s key Southeast Asian partners, which has also signed a recent deal to purchase Japanese arms.)

While this week’s comments represent routine diplomatic housekeeping and don’t tell us much that we don’t already know, they are another signal that relations between Japan and Vietnam seem set to continue on their upward trajectory.