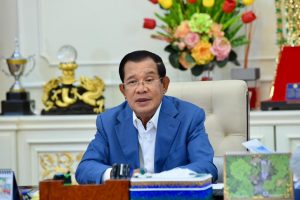

It is an open secret that after 36 years in power, making him one of the world’s longest-serving leaders, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen is thinking about his political exit – something that must be on his mind now as he sits alone during his second forced quarantine of the year. With biting irony, he said last November that he wants to dedicate his post-political career to becoming a lawyer, after spending his political career dismantling Cambodia’s rule of law.

When Hun Sen’s retirement takes places, and who replaces him, are unanswerable queries of the Phnom Penh grapevine. Does he plan to hand power to one of his sons, with most analysts speculating his dynastic favorite to be his eldest, the de-facto military chief Hun Manet? Or does power go to a safe and uncontroversial pair of hands from within the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) rather than the House of Hun? Since last year, the technocratic Finance Minister Aun Pornmoniroth’s name has been thrown into the ring, although this may only be to quell speculation about Hun Manet.

Who takes over is, arguably, secondary and dependent on when Hun Sen resigns. Last December, he said he wanted another 10 years in power. Before that, he said maybe five years. Aged 68, and despite a lifetime of smoking, another decade is plausible. Yet the next few years offer up several opportune moments for retirement.

He could step down before the next election season, with local elections expected to take place in the middle of 2022 and a general election in mid-2023. Of course, these won’t be real elections. The country’s only viable opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), was forcibly dissolved by the government in 2017 over spurious charges of plotting a U.S.-backed coup. Most of its leaders fled into exile, where they will likely remain given that Hun Sen has prevented their return. The party’s president, Kem Sokha, who was arrested for treason in September 2017, is currently awaiting trial.

Instead, the two elections will be plebiscites on the CPP’s rule. Low voter turnout or a large number of spoiled ballots will indicate discontent. At the 2018 general election, with the CNRP banned, more people spoiled their ballots than voted for the second-place party.

But plebiscites on what? If Hun Sen remains in charge during the elections then they will be referenda on his and the CPP’s rule (although the two aren’t synonymous because of Hun Sen’s personalist style). Alternatively, if he steps down before the elections (or only before the 2023 general election), they would be a plebiscite to confer legitimacy upon his successor.

Either option has its pluses and minuses. If he remains in office during the elections, a positive result may only confer legitimacy on Hun Sen, not his successor and not the ruling party. On the other hand, if he steps down before the 2023 ballot and his successor performs badly, that could set up a political crisis which will be difficult to row back from – and a swift return to frontline politics after retirement will indicate that succession is impossible, that Hun Sen has created a system in which no one but him can control, the very definition of a corrupted and incompetent system.

Throwing a further complication in the mix, Cambodia holds the annually-rotating chair of ASEAN next year, a position that will allow Hun Sen to strut on the global stage and be the object of fawning foreign diplomats. (One imagines Hun Sen will not want to turn down such an ego-boosting opportunity.)

More importantly, Hun Sen will not want to risk handing over power before major issues have been resolved. Cambodia’s economy won’t return to pre-pandemic levels before 2022 at the latest. Much hype was made over the World Bank’s latest forecast that GDP will grow by 4 percent this year, after contracting by 3.1 percent in 2020, yet this estimate was the World Bank’s most optimistic one and less reported was its more pessimistic forecast, which predicted growth of just 1 percent this year. Leaving office before the economy (the CPP’s main source of legitimacy) is back on track would be risky.

Neither has Cambodia’s role within the China-U.S. superpower rivalry yet been solved (if it can be solved), in part because of Washington’s paranoia over alleged secret deals involving Chinese military and Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base. Yet Hun Sen’s government is still in denial about the whole affair, seemingly happy to fuel Washington’s concerns at every stage and believing that it can win back U.S. trust by saying it doesn’t want to take sides whilst doing the exact opposite.

Just as complicated is the solution to the Kem Sokha saga, with the detained opposition leader still not having his day in court after his arrest in September 2017, likely because no one wants to try prosecuting the spurious crimes he was charged with. Commentators believe that Hun Sen wants to parlay Kem Sokha’s future release in return for some concession from Western governments. Either that or Hun Sen is holding out in hope that in return for a royal pardon, Kem Sokha will agree to lead a reformed CNRP that exists merely to be subservient to the ruling CPP, providing the necessary facade of democracy to end Western criticism.

Whichever way you look at it, it would be reckless for Hun Sen to retire from frontline politics while Cambodia’s political system and foreign policy remain in a tempered crisis. Until genuine rapprochement with Washington is reached and the CNRP is fully defanged, these problems put the CPP’s power at risk, especially if the party is led by someone else. Hun Sen wants a quiet retirement, not the threat of arrest and imprisonment on the litany of charges that a different government could easily throw at him. He wants the political exit of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, not Malaysia’s Najib Razak.

But that, in essence, is the problem facing Hun Sen. Does he wait for the perfect moment to retire when all of his government’s problems are resolved? Such an ideal moment may never come and, as we have seen, Hun Sen has been more than capable of creating additional problems for himself. Or does he take the plunge and hope that his anointed successor is up to the task?

The longer he waits, the less it appears he trusts any potential successor – and the more he portrays himself as the only capable politician in Cambodia. Hun Sen’s personalist style of leadership, as well as his preference for loyalty over competence amongst ministers and bureaucrats, hasn’t been conducive to bringing through the next generation of leaders. Delay retirement for a decade, and the CPP’s other big hitters will be just as old as him, while younger officials will remain limited in experience because of Hun Sen’s micromanaging style.

Somewhat counterintuitively, though, the COVID-19 pandemic may give Hun Sen a way out. Infection numbers are still spiking after the latest wave began in late April. Some 98.1 percent of Cambodia’s infections have been recorded since May 1. The death toll now stands at 509. Only a foolhardy analyst would speculate about exactly how long this wave will last, but chances are for several more months.

However, Cambodia is now one of the world’s best performers in vaccination, with 21.6 percent of the population having received at least one dose and 16.5 percent now fully vaccinated, according to Our World In Data. According to Reuters analysis, in recent weeks around 94,000 doses have been administered each day on average, which suggests it would take just one a month to vaccinate a tenth of the population, so vaccination of half the population, if not more, is very achievable this year.

If the vaccination campaign maintains momentum, come the close of 2021 the CPP government could be basking in a rare moment of unchecked popularity, even amongst its usual critics. And Hun Sen could emerge from the pandemic with renewed popularity and support, perhaps more so than at any point in recent years.

Does he bow out on a high note, just ahead of next year’s local elections, having been the person who steered Cambodia relatively successfully through one of the worst global crises in a century? Or does he risk losing that high-ground by delaying his exit for several more years, during which time new problems and complications arise, and pandemic successes are forgotten?

The question, then, is what is more important to him: his own legacy, the fate of his CPP party, or the stability of the country?