Since Xi Jinping’s first proposed a “21st Century Silk Road” during his visit to Kazakhstan in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been defined as China’s regeneration of trade with Eurasia. The BRI has evolved to become the central concern of the economic relationship with Central Asia and the Middle East.

Purposefully recalling the ancient Silk Roads that connected Europe and the Middle East with Chinese imperial dynasties, China has been investing its efforts and capital to revitalize infrastructures and boost economic exchange with developing countries in Asia and Africa, having committed $1.4 trillion to this plan. The BRI focuses on infrastructure development of the countries located between China and Europe and aims to shift the center of international trade from the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean to the Eurasian continent.

Nevertheless, China’s ambition to be the center of the global trade system is already creating friction with its partners. For instance, the BRI has been criticized for skyrocketing debts. According to the Center for Global Development, eight BRI recipient countries – Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan – are at high risk of debt distress. Sri Lanka also leased its Hambantota port to China in 2017 after it was no longer able to repay loans to the Chinese lender. The Hungarian government has recently met with public protest resisting the plan to open a campus for Fudan University – a Chinese university – in Budapest.

These controversies feed into suspicions that the BRI is not only about trade but is part of a Chinese strategy to increase leverage over BRI countries, economically, politically, and militarily. The U.S. is leveraging these concerns to turn global public opinion against the BRI and pressure countries to avoid Chinese infrastructure investments and financing. These tensions show that if the BRI is only concerned with China’s economic and security objectives, without considering the local conditions of recipient countries, it may eventually result in high discontent and opposition.

The ancient Silk Road, in fact, was not exclusively about trade but also facilitated many types of exchanges between China and other countries along the ancient route. These exchanges are particularly visible in the Middle East region, where Islam is the dominant religion. Cultural and religious exchanges have been important throughout the history of the relationship between the Middle East and China. The Hajj or Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca led to the forming of a Chinese diaspora in Mecca and its vicinities, which included Chinese Muslims who established inns to provide lodgings for pilgrims from China.

Dr. Janice Hyeju Jeong, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Göttingen, recently gave a lecture on Mecca and the Chinese Muslim community in Saudi Arabia for an interdisciplinary research project – Infrastructures of Faith: Religious Mobilities on the Belt and Road (BRINFAITH) – at the Hong Kong institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (HKIHSS). In her lecture, she suggested that Islam and Chinese Muslims’ pilgrimage to Mecca was one of the pivot points that first drew China and the Middle East together.

Pilgrimage and Chinese Muslim Diaspora in Mecca

Chinese Muslim communities, most of whom resided in Western China, have existed since the 8th century CE. These people – once known collectively as the Hui or Huihui – are now classified as members of 10 separate ethnic groups, including the Hui, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Dongxiang, and others.

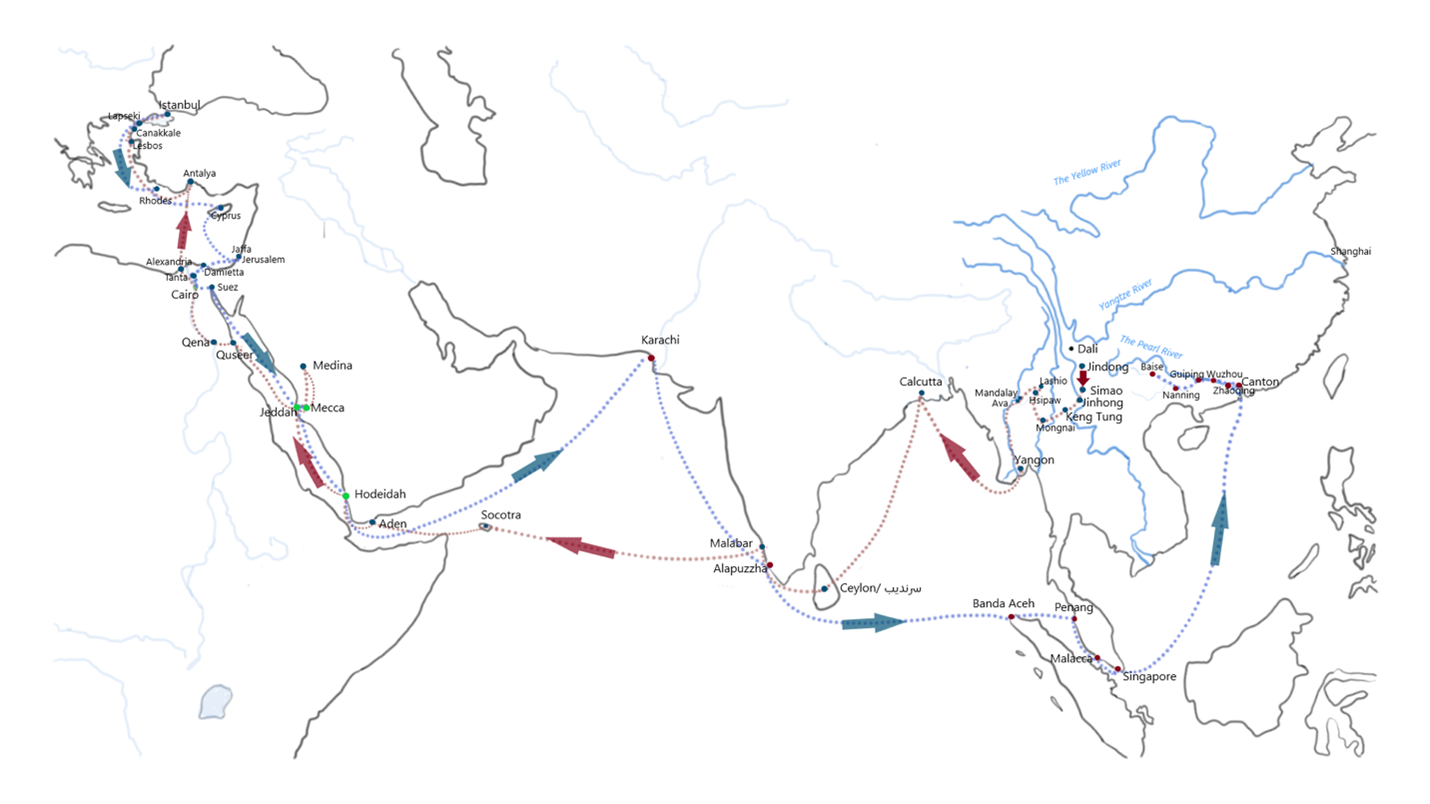

Due to their religious faith, the Chinese Muslims also carried out the Hajj – the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca. Global connectivity and a sense of crisis in the 19th and 20th century created a desire among Chinese Muslims to connect China and the Arabian Peninsula, which was perceived as the center of the Islamic world. Thus, the travel route between China and the Middle East was revived starting in the 19th century, amid China’s incorporation into the international system led by the Western countries. For instance, Ma Dexin (1794–1874), a Hui Chinese scholar from Yunnan province in the southwestern part of China, went on the pilgrimage to Mecca between 1840 and 1848. The route started from Yunnan, led through Burma and the Indian Ocean, and eventually reached the Arabian Peninsula.

Ma Dexin’s pilgrimage route, 1840-1848. Source: Dr. Janice Hyeju Jeong

“Although it was a time of great influence of the British Empire, in its interest in shipping, it was also space of encounters for Ma Dexin,” said Jeong. “In Yangon, he stayed with a merchant from Surat, and in Mecca, he stayed in a house of a Jawi person, referring to Malay people.”

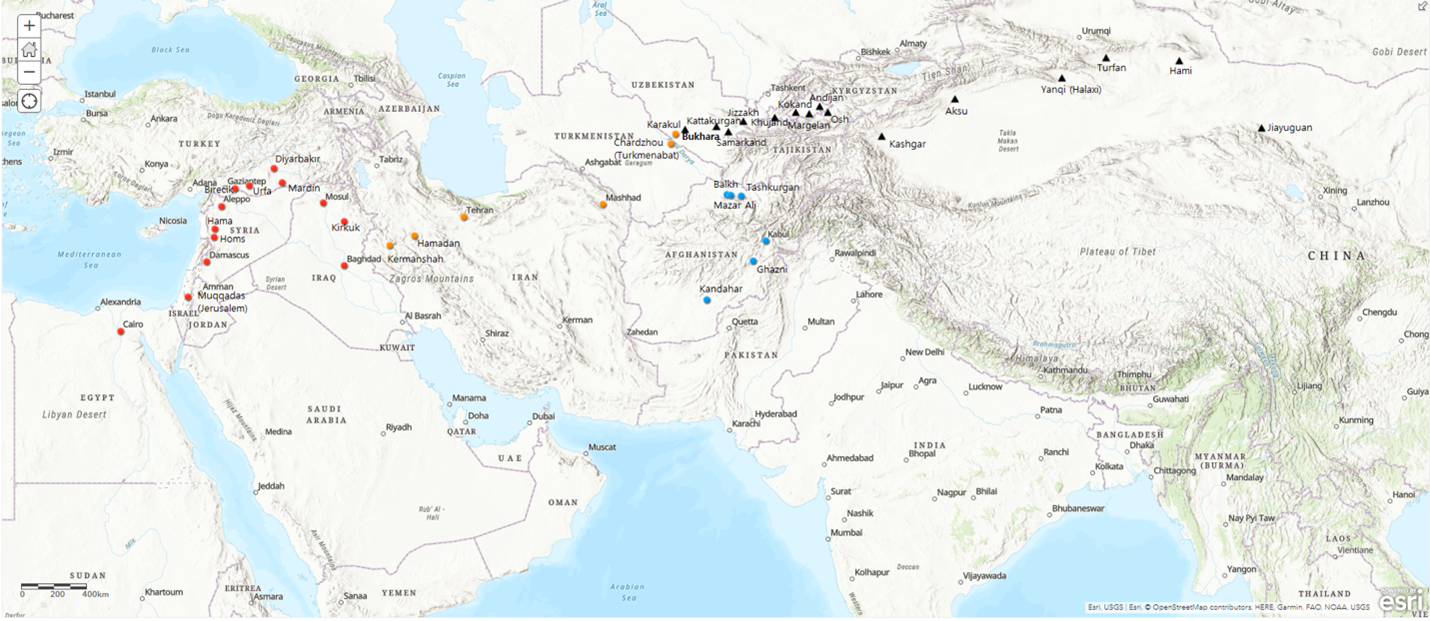

The pilgrimage route is significant in studying China-Middle East relations. It resembles the maritime BRI route with the Indian Ocean as the center of the trade. Ma Dexin’s records of the “northern route” to Mecca, which passes through Central Asia and Iran, also show similarities to the current continental BRI route.

The northern route to Mecca. Source: Dr. Janice Hyeju Jeong

As the destination of the Muslim pilgrimage route, Mecca was a home for diaspora populations. The city and the area around it had a cluster of diaspora communities from across Asia. Thanks to the pilgrimage route and increasing exchanges between China and the Middle East and political turmoil in post-Qing China, it was estimated that about 2,000 “Overseas Chinese” were residing in the Hejaz – currently part of Saudi Arabia – by 1939. Most of them comprised Turkic Uyghur Muslims from Xinjiang and also a number of Hui Muslims from western China.

The turning point for the Chinese Muslim diaspora was the defeat of the Nationalist government in the Chinese Civil War. Some Muslim escapees from Communist China sought exile in Mecca when the Nationalist government fled to Taiwan, resulting in a surge of the Chinese Muslim diaspora community in Saudi Arabia. For instance, Ma Bufang (1903 – 1975), the warlord and governor of Qinghai province who had allied with the Nationalists, was airlifted to Taiwan by former U.S. naval officer Claire Chennault’s transport service and escaped to Mecca after the Communist government achieved victory in the northwestern frontier.

“This airlifting shows how the mode of the transport was changing for the Hajj,” said Jeong, “as well as being the turning point for the formation of the Chinese diaspora community in the Hejaz.”

Ma Bufang stayed in Mecca as a part of the Hajj and later as the leader of a Taiwanese Islamic pilgrimage delegation. Jeong suggested that the Hajj played a role as a convenient excuse for the Chinese Muslim political leaders to seek exile away from the Communist Chinese government and stay in Mecca.

The sojourns of diaspora communities in Mecca were facilitated by institutions known as the waqf, or property endowments for charitable and religious purposes. The Chinese waqf houses in Mecca operated similar to Huiguan – a meeting hall for Overseas Chinese immigrants – and they were constructed with donations from various Chinese Muslim communities around the world. The waqf provided lodging for Chinese Muslims coming to Mecca for pilgrimage purposes.

The Chinese Muslims’ waves of exile to Mecca during the Cold War, however, did not mean that interactions between people and religious values were completely halted between the Middle East and mainland China. Before the normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and the People’s Republic of China in 1990, unofficial family reunions were held in Mecca in the 1980s through mediation of the World Muslim League or visas for family visits. Although anti-communist in its initial years, the World Muslim league managed the sensitive political issues between China and Saudi Arabia by enabling the Chinese Muslim diaspora population’s reunion with their families from the mainland with an “excuse” of pilgrimage to Mecca. Religion, therefore, was the bond that connected China with the Islamic world during this period of the Cold War tensions.

“That was also a chance for second generation individuals to discover new homes,” said Jeong. “Creating a connection with their old homes in mainland China was a source of another identification and also a sort of social capital.”

As China opened its economy and the Cold War approached its end in the 1980s, the connection between China and Mecca also provided opportunities for the Chinese Muslim diaspora to return to their homeland. After the Cultural Revolution’s destruction of cultural traditions, the revival of these heritages in the post-Mao era allowed the fluorescence of religious activities in the 1980s and 1990s. Thus, it was much easier for the Chinese Muslim diaspora to return to their home in China, and it also contributed to China’s closer relations with Middle Eastern countries.

Jeong’s lecture suggested that Chinese Muslims’ pilgrimage and its diaspora in Mecca is a crucial part of the interaction between China and Middle Eastern countries. The dynamism of Chinese Muslims’ pilgrimage to Mecca preceded the BRI’s connections across China with Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, Central Asia, and the Arabian Peninsula. It shows that the interaction between China and the Middle East also incorporated religious values, along with political and economic ties. The Islamic religion was one of the bridges that originally connected the two regions – Mecca as a magnet for diaspora and a mediator of transnational connections.

Lessons From the Chinese Diaspora Community in Mecca

How Chinese Muslims played a role as a bridge that connected China and the Middle East shows that the economy cannot be the sole source of cooperation between the regions of the BRI. Cultural and religious dynamics should also be considered when promoting cooperation in inter-state relations. If the BRI aims to increase connectivity between China and other regions, its strategies and projects will need to consider the religion and culture of its partner countries rather than simply luring them with a pot of gold.

Nevertheless, the religious aspect of the ancient Silk Road is largely neglected in the modern planning of the BRI, and it does not leave much space for cultural interactions. State-owned enterprises participating in the BRI have been criticized for the absence of mutual exchanges with and understandings of local communities, and the local populations often find it difficult to understand the intention of the BRI.

Furthermore, Beijing has been also criticized by Western countries for its domestic human rights record concerning freedom of religion. Political control over religious communities has been escalating in the past decade, with the government ordering all religions in China to be “Chinese in orientation” and attempting to assimilate ethnic minorities’ culture into a stronger Chinese identity to weaken secessionist movements.

These policies – notably in Xinjiang, where “re-education camps” aim to turn Uyghurs into loyal followers of the CCP – have led to allegations of “genocide” by Western countries. Criticisms of China’s human rights issue are also explicit in the recent joint statement from the Group of Seven (G-7) – the U.S., the U.K., France, Germany, Italy, Canada, and Japan – summit in Cornwall, England. During the summit, the G7 leaders discussed strategic competition with Beijing and their response against China’s rising economic and military power, where they adopted a statement condemning alleged forced labor in Xinjiang while also announcing a “Build Back Better World” initiative (B3W) as an alternative plan to rival the BRI’s infrastructure partnership with developing countries.

“The point is that China has this Belt and Road Initiative,” said U.S. President Joe Biden, in his remarks during the press conference at the G-7 summit, “and we think that there is a much more equitable way to provide for the needs of countries around the world.”

The summit had two implications. First, China’s BRI is now increasingly being framed by Western countries as a plan that goes against the cultural and religious values of its partner countries. China is now accused of domestically oppressing the cultures and religion of its Muslim ethnic minorities, increasing suspicions and doubts among governments and the people in BRI partner countries. If the BRI cannot manage this resistance, it will not achieve its goal and could instead meet increasing resistance.

Second, values are as significant as economic motives in inter-state relations. In the announcement of the B3W, the White House included “value-driven” as one of its core principles, promising that it will be “carried out in a transparent and sustainable manner – financially, environmentally and socially.” While some critics have dismissed the G-7’s ability to finance the B3W and questioned the hypocritical and patronizing attitude of Western warnings to BRI partner countries, there is no doubt that cultural and religious values will become an increasingly salient dimension of discussions and strategies related to the BRI.

“It is not easy to separate commerce, trade, or economic exchanges with the transfer of religious ideas and persons because they are carrying those practices with them,” suggested Dr. Jeong, “so I think that is sort of default of things that you cannot stop ideas and religion from traveling together with commerce.”

Pilgrimage and the Chinese Muslim diaspora in Mecca provide a historical example of how non-materialistic values, such as religion, are an intrinsic part of the relationship between China and other countries. Without taking into account the religious dimension of China-Middle East relations, the BRI may hit bumps on the way to building a “21st Century Silk Road.”