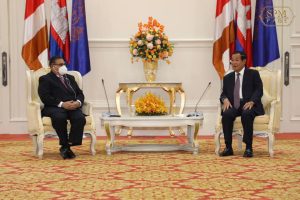

Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen will visit Myanmar early next month at the invitation of the country’s military junta, as he seek a solution to the current political crisis. Hun Sen will reportedly meet with the junta’s chief, Min Aung Hlaing, who seized power through a military coup on February 1.

The move by Hun Sen is likely to ensure that Myanmar’s military government will be included in talks within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) during Cambodia’s chairmanship of the bloc in 2022, after it was excluded from the ASEAN Summit and related meetings in late October. In announcing his visit, the Cambodian leader stressed that he would try to achieve the restoration of cooperation and solidarity within the bloc.

Such an approach is not new. Indeed, it is a part of ASEAN’s long-standing practice of constructive engagement, which embraces political dialogue in the solution of regional problems – a process that helped ensure the reintegration of Myanmar into the regional community and paved the way for its democratic transformation more than a decade ago.

However, it remains uncertain whether the Cambodian leader’s visit will yield political results, and it has already divided opinion. Some pundits claim that Hun Sen’s pragmatism and past experience in handling his own country’s civil war could be beneficial in addressing the current political crisis. Others have lambasted the move, arguing that Cambodia is making the situation worse by according formal recognition to the junta.

Frankly speaking, I think that the move could be a positive step. Essentially what Cambodia is trying to do is to create a favorable environment for the resumption of direct talks between ASEAN and the leadership in Myanmar. Like it or not, regardless of its political legitimacy, one must accept that closing the one last remaining door to possible engagement with the military regime, which controls most of the country and the security forces, will only end up prolonging the dire humanitarian situation in Myanmar.

As incoming ASEAN chair, Hun Sen’s visit will at least pave the way for ASEAN to secure a conduit of communication that eventually enables the opening of a constructive dialogue or negotiation, one of the five points of consensus that ASEAN agreed in April. The longer we exclude Myanmar from the talks within ASEAN frameworks that offer an opportunity for negotiation, the worse the humanitarian crisis in the country will become. Those who will suffer the most are vulnerable groups, particularly civilians, whose livelihoods have already been affected by the socioeconomic catastrophe driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We have also learnt that isolation doesn’t work in the way we would all wish, and that sanctions often do not produce the result we want when it comes to solving international crises. Targeted regimes can always find ways to withstand pressure and punishment, while disadvantaged groups of citizens often suffer instead.

So, what next? There is no magic solution to any international crisis. This is particularly true of the crisis in Myanmar, where military regime has killed over 1,300 people since the coup.

We can all agree that Myanmar’s political crisis is far more complex and challenge for any single country or regional organization to settle effectively. However, a regional grouping like ASEAN remains the most suitable actor to continue the efforts in assisting Myanmar and its people in finding some sort of solution.

Given ASEAN’s limited influence and political leverage over the junta, this necessitates that it receive instant and durable assistance and support from its main international partners. A solution to the crisis, of course, rests upon the conflicting parties and could take much longer, but outsiders need to increase their efforts and work together to speak with a single voice in buttressing ASEAN’s measures in order to prevent further violence by the military regime and the unnecessary loss of innocent lives.

In addition to that, an individual state like Cambodia, as ASEAN’s incoming chair, also has an important role in making sure that the door will be open for international support to the people of Myanmar. The situation requires unified and sustained assistance from major and middle powers such as the United States, China, Japan, India, Australia, South Korea, and the European Union. All can do a lot more to help ASEAN with formulating immediate solutions to address the country’s humanitarian and socioeconomic crises.

Regarding the external actors’ support, Hun Sen revealed that he discussed the Myanmar crisis and his possible visit to Myanmar during his recent conversation with Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. However, other major powers should also sign up and find ways to support Cambodia’s chairmanship in order to achieve more practical and effective solutions.

Despite the fact that any initiatives that take place under Cambodia’s chairmanship are unlikely to go beyond the ASEAN Charter and the bloc’s “non-interference” principle, which Hun Sen emphasized earlier this week, it still is desirable for him to use his personal connections and be as candid as possible in relating to Min Aung Hlaing some difficult-to-swallow realities.

These might include the fact that the longer he and the Tatmadaw hold power, the greater the chance they will be held to account for their present and past abuses, and that a power transfer to civilian leadership through democratic elections remains the only way for the country to get out of its present political quagmire and prevent a continuing bloodbath.

Once all these can be attained, ASEAN will, to a certain extent, have some leverage to affect the political trajectory in Myanmar. But divisions among ourselves will only offer advantages to the military junta, allowing it to consolidate further its power and complicate the pursuit of a peaceful solution.