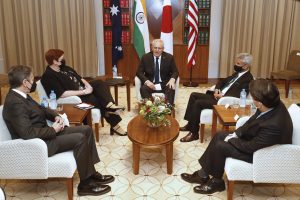

Ever since it was created, the Quad has meant different things to different people at different points in time. But when its foreign ministers came together in Melbourne last week, one thing was rather clear: India was the odd one out on several critical geopolitical issues.

Take the twin troubles in Myanmar and Ukraine, for instance. While the joint statement mentioned the crisis in Myanmar and called for a “[swift] return to democracy,” Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar made clear to his three counterparts that his government does not agree with Western sanctions.

The gap on Ukraine was even wider. In the post-meeting press conference, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken warned that a Russian invasion “could begin at any time” and his Japanese and Australian counterparts both voiced concerns over Russia’s military buildup on the Ukrainian border. But Jaishankar chose to maintain silence on the issue and Ukraine did not find any mention in the joint statement.

Human rights values are increasingly a source of friction between India and the rest, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi continues to accelerate the Hindu nationalist agenda. Through much of last week, multiple states across India were in the throes of a dispute over whether the hijab — the Muslim headscarf — should be allowed in educational institutions, after some Muslim students were barred from attending classes for wearing it. Amidst the kerfuffle, the U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, Rashad Hussain, tweeted that bans on the hijab “violate religious freedom.” India responded by saying that “motivated comments” were not welcome.

Even on China — the apparent raison d’être of the grouping — India has broad disagreements with the rest of the Quad. India’s own concerns vis-a-vis Beijing are very narrow — limited to the border dispute in the Himalayas. It has little interest in the atrocities in Xinjiang and has expressed no distress over the situation in Taiwan or Hong Kong.

India’s reaction to the Beijing Winter Olympics was particularly telling. While the U.S., Japan, and Australia announced a diplomatic boycott of the Games over human rights concerns, India had initially backed China’s role as host. But after Beijing featured one of its injured soldiers from the Galwan clashes as an Olympic torchbearer, India belatedly decided to join the boycott.

Meanwhile, concerns over troubles in East Asia are a world away, so far as New Delhi is concerned. While North Korea’s recent missile testing spree was condemned by the joint statement, India has personally maintained silence on the issue for years. Of the four Quad members, New Delhi is the only one with diplomatic presence in Pyongyang.

In the eyes of most people in New Delhi, India has the most to lose in a confrontation with China, owing to the long and treacherous land border in the Himalayas. But the rest of the Quad does not share that concern. As a result, the Quad now appears to function largely as a forum to discuss development. Apart from the COVID-19 vaccine drive, last week’s meeting also furthered the agenda on such things as climate change, cybersecurity, infrastructure development, and education.

A purely developmental agenda certainly has its uses, especially to India — the coalition’s least industrialized member. But the widening gap on geopolitics will have its own impact on the durability of the Quad.

Owing to its size, geographic location, and demographics, India can be an important asset to the West as its rivalry heats up with the new axis between China and Russia. That is why the U.S. has consistently invested in India’s rise. Even in its latest Indo-Pacific Strategy document, published early this month, Washington listed a “leading India” as one of its strategic priorities and pledged to “support [India’s] role as a net security provider.”

Yet, as the difference in values deepens and common geopolitical ground diminishes, the U.S. and its allies may be left with less incentive to invest in India’s rise or its capabilities. They may also be wary of even seeing New Delhi as a partner on key geopolitical issues.

The AUKUS partnership between Australia, the U.K., and the U.S., in some sense, appeared to be the result of a quiet realization in Washington that it needs more reliable partners in the Indo-Pacific to pursue common security interests. As the Quad evolves, it appears likely to do less geopolitics work and more knowledge-sharing on basic developmental challenges plaguing India.