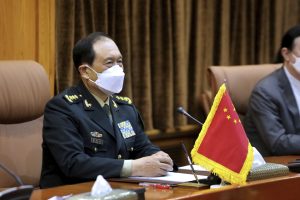

In late April, Chinese State Councillor and Minister of National Defense Wei Fenghe embarked on an official trip that took him to Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Oman. Although his trip went largely unnoticed by the international media and news outlets, the significance of it cannot be overstated. It could herald the beginning of an effort by Beijing to better monitor and influence the scope of India’s International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

China’s expanding influence in Central Asia has been strongly underpinned by a sense of unease with the prospect of NATO and/or U.S. presence in its backyard. Ironically, the most salient factor behind India’s outreach in the same region is the growing unease amongst Indian officials with regard to China’s omnipresence in both their immediate neighborhood and Central Asia. Concerned with warming ties between China and Russia as well as the fast expanding Sino Pakistani relations, Indian officials worry about the prospect of encirclement by China.

To counter Beijing’s moves, India, especially since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has embarked on an attempt to delegitimize China’s initiatives in the region. New Delhi seeks to cast doubt on the intentions of the Chinese government by dismissing its economic proposals as neocolonial efforts aimed at rendering other states totally dependent on China via a debt trap. India is also promoting INSTC as a viable and fairer alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). New Delhi’s grand geopolitical strategy is motivated in part by the dual goals of challenging and delegitimizing China’s BRI in resource-rich regions of the world, including Central Asia and Africa.

Wei’s recent trip indicates that Beijing seems to have woken up to the brewing Indian challenge to its neo-mercantilist agenda of utilizing trade and investment as tools in service of geopolitical ambitions.

Depicting China as a reliable strategic partner, the Chinese defense minister used his visits to Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Oman to call for marked expansion of high-level strategic communication as well as further deepening of military exchanges and more frequent joint exercises and personnel trainings between China and the four nations. However, Wei’s consistent reference to the United States and “others” playing allegedly destabilizing roles indicates that his bombastic remarks had less to do with U.S. strategic posturing in Central Asia and more to do with that of India.

On the last leg of his trip in Muscat, in fact, Wei did not even mention the United States when expressing his country’s desire for closer military and strategic cooperation with Oman.

Beside having close cultural and communal ties with India, Oman is a major node on INSTC, whose recently inaugurated special economic zone in Duqm is an ideal destination for the establishment of clearing houses as well as manufacturing hubs for Indian businesses with operations and/or interests in Iran and countries of Central Asia, the Caucasus, and indeed Russia. Located at the edge of the Indo-Pacific Ocean and within close proximity to India’s own major port cities as well as East Africa and Strait of Hormuz, Duqm is also a geostrategic hotspot ideal for efficient transshipment of military equipment or personnel and refueling of naval assets.

The other stops on Wei’s itinerary are also key parts of INSTC. Iran constitutes the jewel of India’s grand design, allowing New Delhi to bypass Pakistan by providing it with a direct land route to and from Central Asia and Afghanistan via the Iranian Port of Chabahar. As such, INSTC’s viability as a trade corridor rests largely on India’s ability to have uninterrupted access to Chabahar and its freight-forwarding facilities. Turkmenistan’s significance to India lies in its vast gas resources and its pivotal role as the sole supplier of the long-stalled TAPI pipeline which, should it ever come online, complements India’s efforts at diversifying its energy supply routes. Kazakhstan, finally, matters to India as a reliable supplier of much needed uranium for India’s nuclear power plants while its market is an attractive destination for not just Indian goods but also technology, teachers, nurses, and doctors.

India’s stakes in the quartet’s sociopolitical stability and goodwill are set to grow hand-in-hand with its efforts to expand its commercial footprint in Central Asia. Becoming a key defense and security partner for these nations, therefore, provides Beijing with strategic leverage that it could use, and indeed benefit from, in its dealings with India. By forging closer strategic ties with these countries, China can exert indirect yet critical influence over the volume of Indian trade passing through these countries.

China is unlikely to be able to prevent India from executing its INSTC and expanding its presence in the countries that lie alongside the corridor. That said, if Beijing can position itself as a major, if not the main, defense and security partner for Oman, Iran, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan, it could control the extent of New Delhi’s influence and regional reach.