Climate change mitigation represents the greatest governance challenge for every country in the world. While there is a technological component to the much-needed transition to renewable energy, building support for this response among people who are currently dependent on the consumption and production of fossil fuels constitutes a bigger impediment. South Korea can play a larger role in helping the global community overcome this political impasse by sharing insights drawn from its successful reforestation campaign.

At the end of the Korean War, over 30 percent of the previously forested land in South Korea had been nearly depleted or completely denuded. In addition to the significant wartime damage, the woodland was further devastated by the population’s reliance on fuelwood for heating. Many impoverished farmers on rugged hillside plots without access to fertilizers also depended on slash-and-burn agriculture, torching what little foliage was left to bolster nutrients in the soil. These practices persisted through the 1950s, accelerating the rapid deforestation of the country.

The repercussions of this runaway exploitation were deeply felt by the local communities. Loose soil on the bare hills and mountains gave way during heavy rainstorms, causing significant ham to farming. In addition, the depletion of the natural environment reduced the stock of forageable plants, which the food-insecure population consumed to complement their diet. Despite these pains, a ban on tree cutting was not enforceable due to its centrality to the rural economy.

South Korea’s targeted response to deforestation began in the 1960s. The military junta that seized power in 1961 staked its legitimacy on economic growth, and identified forest management as a critical enterprise for improving the people’s livelihood. Without many capital resources or technical skills to speak of, the government’s approach focused on three areas: address the sources of deforestation; empower the agents of change; and establish a system of accountability.

The government correctly diagnosed that demand for affordable fuel and poverty among farmers occupying particularly barren hillside plots were the main drivers of the problem. With loans from both the U.S. Agency for International Development and the World Bank, South Korea focused on developing domestic sources of fuel and the transportation infrastructure to deliver it to the population. The country’s decision at the time to bolster coal production is one of the reasons why South Korea is today a major contributor to carbon emissions – but the shift to coal also meant a shift away from fuelwood, which helped curb deforestation.

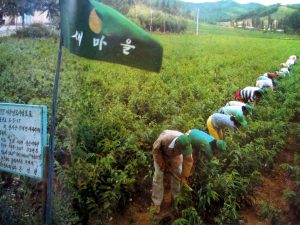

For the poorest rural communities that relied on slash-and-burn farming, policymakers offered them new options. In addition to new homes and schools for children, they were offered public sector work, including tending to saplings for the reforestation campaign. Moreover, the rapid industrialization of the South Korean economy meant that the rural poor had job opportunities elsewhere that offered better wages than near-subsistence farming.

As deforestation slowed, the Korea Forest Service (KFS) led the reforestation effort. On top of consistent political support, the government empowered the agency by transferring it from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Home Affairs in 1973. This proved to be an important reorganization because Home Affairs oversaw local government offices, allowing the KFS to marshal on-the-ground personnel (in particular, village-unit officials and local police) for policy implementation. With this authority, the KFS launched initiatives that would have been unimaginable otherwise, such as the nationwide mobilization of local elementary school students for tree planting.

As these efforts relied heavily on the movement of significant resources to public and private actors in countless localities, the threat of corruption always loomed large over the reforestation project. In particular, the South Korean government worried that local government officials would collude with one another to underperform and skim public money for themselves. To ensure accountability, the KFS mandated that reforestation initiatives would always be audited by officials from a neighboring province. As an added safety measure, the Ministry of Home Affairs made the inspecting official and the local administrator compete for promotions, further reducing the incentive for collusion.

The flow of accurate information moving up to the central KFS office through this system of checks allowed policymakers to be more responsive to problems and properly reward successful initiatives, creating a virtuous cycle of good performance.

International observers like the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization began recognizing South Korea’s achievements by the early 1980s. There are many ways to measure the success. For example, during the late 1950s, 58 percent of the mountain forests were bare; this was fully reversed by the late 1980s.

Perhaps the most startling statistic is that the country’s revived woodlands hold 18 billion tons of water, a figure that exceeds the 14 billion tons that its 49 dams hold back. This hints at the amount of soil erosion, flooding, and other natural disasters that South Korea prevented by restoring its forests.

What South Korea achieved was the result not of a technological breakthrough but of the successful organization of local communities and state bureaucracy.

There were some errors committed during this process. The reforestation relied too heavily on planting rapidly-growing coniferous trees; the lack of species diversification made the new forests susceptible to pests and disease outbreaks. Moreover, the reforestation did not reduce the domestic appetite for wood and South Korea remains a major importer of timber from countries most heavily affected by illegal logging.

Nonetheless, South Korea’s success is undeniable and it has served as a model for other countries pursuing reforestation. Since 1991, the Korea International Cooperation Agency has been supporting similar projects in China, Mongolia, Myanmar, and Indonesia. The South Korean government also invited forestry managers from Dominica, Papua New Guinea, Ethiopia, and elsewhere to share with them best practices.

But South Korea’s experience is not just instructive for reforestation initiatives. The fundamental challenges the KFS faced when it set out to stop the impending ecological disaster are more universal: securing buy-in for change from stakeholders who relied on the old system; utilizing sufficient state authority to achieve the intended goal; and keeping those in power accountable to the public. This has broad applications for climate change mitigation. Policymakers in both emerging markets and advanced economies face political opposition to reducing carbon emissions from impacted workers (like the 2019 protests in Ecuador and the ongoing yellow vests movement in France) and also elites with significant personal wealth invested in coal (like U.S. West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin).

South Korea shows one path forward from these seemingly intractable impasses – as long as the top political leadership has the will to pursue it.