The first half of 2022 was challenging for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its general secretary, Xi Jinping. He is facing a “year of instability,” said Kevin Rudd, and “may not get his coveted third term because of the mistakes he has made,” according to George Soros. Those assessments notwithstanding, Xi appears well positioned to tighten his grip on power at the CCP’s 20th National Congress, now just months away.

Congress years in China typically see a flurry of political activity, as senior officials compete to join the bodies that will steer Chinese policymaking over the subsequent five to 10 years. Delegates to the CCP’s National Congress are first selected by congresses in China’s 31 provincial-level regions, which have all now concluded. In half of these regions, the party secretary has been replaced during the past year, representing a significant turnover in local leadership.

Among the appointees are numerous allies and associates of Xi, including Liang Yanshun in Ningxia, Ni Yuefeng in Hebei, and Sun Shaocheng in Inner Mongolia. Meanwhile, many existing Xi protégés leading China’s largest population centers have been reconfirmed in their roles, at least until the National Congress. This means that Cai Qi in Beijing, Li Xi in Guangdong, Chen Min’er in Chongqing, and even Li Qiang in COVID-troubled Shanghai should all be reappointed to the Politburo.

Increasingly, Xi’s allies are dominating not just the major territorial positions but also key functional areas of government. Take the new minister of public security, Wang Xiaohong, who held senior policing roles in Fujian during the 1990s and 2000s, while Xi was rising through the province’s political ranks. Wang is the first former police officer to become public security minister in over two decades, which may signal that Xi plans to further prioritize law enforcement during his next term.

The most important rivals to Xi and his allies are the Tuanpai, officials who rose through the Communist Youth League under former President Hu Jintao and outgoing Premier Li Keqiang. But their influence has waned significantly during Xi’s first two terms, and several Tuanpai stars have recently been sidelined from front-line politics.

One is Chen Quanguo, who gained international infamy as Xinjiang party secretary. After an unusual six-month hiatus since leaving that post, Chen was confirmed as deputy head of the Central Rural Work Leading Group in June, making it probable that he will leave the Politburo. Another fallen star is Lu Hao, formerly natural resources minister, who was effectively demoted to head the State Council’s Development Research Center. Once China’s youngest ministerial-level official, Lu studied at Peking University under the same economics professor as Li.

Apart from these personnel changes, the local congress season was notable for the praise that Xi received from regional leaders, both allies and rivals. Li Hongzhong, the Tianjin party secretary and a member of former President Jiang Zemin’s faction, instructed officials to “emotionally” love Xi. Wang Weizhong expressed his “eternal gratitude” to Xi more than 10 times upon becoming Guangdong governor. And there was similarly effusive language from Yuan Jiajun, the party secretary of Zhejiang province, who called on officials to show a “heart of gratitude, love and respect” to Xi.

Some of the most pious acts of devotion came in the southwestern region of Guangxi, where local officials declared that “the leadership of General Secretary Xi will surely pool greater strengths of the times and steer China toward its great rejuvenation.” Guangxi’s capital, Nanning, even started issuing little red books of Xi quotes, before scrapping the initiative due to its uncomfortable Maoist associations.

All of this is a prelude to the 20th National Congress, when we will find out the makeup of China’s most influential decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). In fact, its membership may already have been decided by senior officials and retired “elders” through closed-door deliberations and straw polls. For now, we can only speculate about who may be leaving and joining the PSC.

According to veteran analyst Cheng Li, only one member, Li Zhanshu, is expected to retire this year. In this scenario, both Xi and Han Zheng, as well as another older Politburo member, perhaps Liu He, will be re-appointed past the age limit of 68 that has been enforced in recent decades. Such an arrangement would bring continuity to Xi at a time of significant policy challenges, while also making his contravention of age norms seem less personalistic.

But if Xi and his confidants postpone their retirements, it could legitimize factional rivals to do the same. Xi also appears to be slowing the rise of younger leaders, with regional party committees now substantially older than they were 10 years ago. The resulting risk is that China relapses to the gerontocracy of the Mao and Deng eras, creating a dearth of future leadership talent.

Because of this concern, as well as Xi’s desire to further consolidate his power, it may be that only Xi himself will stay on past age 68, as analysts like Neil Thomas suggest. Or, as Alice Miller and others propose, Xi could relinquish the role of general secretary to a confidant, while assuming the superior office of party chairman, which has been dormant since 1982. However, there have been no strong signals that Xi will take this approach, which risks destabilizing China’s established power structure.

If there’s anything we know for sure, it’s that party congress years tend to throw up political surprises. 2012 saw the downfall of Bo Xilai and Ling Jihua, who were both PSC contenders, while 2017 saw the purge of Sun Zhengcai, once seen as a successor to Xi. So far, the biggest political scandal of the current transition period happened last November, when tennis star Peng Shuai made her much-publicized claim of sexual assault against former PSC member Zhang Gaoli.

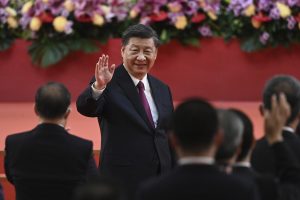

But Xi Jinping appears confident and projected this confidence while visiting Hong Kong on July 1, his first trip away from the mainland since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He and other members of China’s political elite will now prepare for their traditional summer retreat at Beidaihe. And with his position looking secure, Xi might decide to spend time less on political horse-trading and more time putting his feet up.