Who says Chinese Communist Party Congresses are scripted and boring?

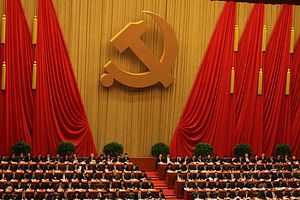

On the surface, of course, they appear to be. These mega-meetings feature the top 2,200 or so party officials in China, all dressed in identical suits lest any hint of individuality be permitted to slip out (except, ironically, for ethnic minority delegates, who are in full ethnic dress to emphasize the CCP’s diversity). The gathering seem to be nothing but one-dimensional stage shows reflecting years of opaque processes by which the men who will lead China for the next five years have already been chosen. There is no public discussion, no public debate, and certainly no public drama ahead of the unveiling of the people set make decisions affecting every Chinese citizen in most areas of life.

By definition, therefore, Party Congresses are supposed to be surprise-proof. The events that unfold on TV screens are the culmination of months, indeed years of building relationships, testing alliances, and lobbying CCP-style for advancement. The eventual solidarity shown to the world during Party Congress week hides the personal and political carnage from which a cohesive face of party leadership is then born.

But there is always hope for something out of the ordinary, an ad lib remark or an unexpected event, anything that might show some substance, some character, indeed some style.

That hope was realized in at least one previous Party Congress.

In 2012, the 18th Party Congress served up not just one or two, but three surprises, according to an analysis by Damien Ma in The Atlantic following the close of proceedings in Beijing.

The first surprise was an unexpected but highly consequential cameo by former Party General Secretary, President of China, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission Jiang Zemin.

Jiang dominated the Chinese political scene from the late 1980s through the early 2000s, holding on to some leadership positions until 2005. It had been rumored that he was ill, perhaps terminally, so when he followed then-General Secretary and President of China Hu Jintao into the Great Hall of the People at the opening of the 18th Party Congress, it became clear to the world that Jiang Zemin was still very much in power in China, and needed no title in order to wield it.

By the end of the Congress, Jiang had managed to place at least three and perhaps as many as five of his anointed proteges onto the Politburo Standing Committee, the most powerful seven men in China. Jiang’s influence and legacy within the halls of Chinese power exist until today.

Ma identified two further surprises from the 2012 Party Congress.

The first was that Hu Jintao, outgoing president and party general secretary, let go of his chairmanship of the Central Military Commission. Xi Jinping, taking over both political and party posts from Hu, therefore had the added benefit of acquiring immediate power over the military, giving him the triumvirate of posts that defines the pinnacle of power in China. By contrast, Jiang held control of the CCP’s military (for that is what the PLA is) until 2005, three years after Hu had formally taken over the reins as China’s top leader.

And finally, the surprise of Xi Jinping’s “likeability” made an impression not only on Ma, but on much of the general Chinese population. Ten years after Xi’s accession to the top of China’s power pyramid, it may be forgotten that when he first took over, he was widely liked and praised – as was his wife – throughout the country. He apologized for being late in coming out to make his speech. He spoke in a standard Mandarin Chinese appreciated by and accessible to all Chinese, as opposed to the provincial brogue of Hu Jintao. Ma went so far as to say that Xi Jinping’s “affable, plainspoken demeanor is the big story of the power transition.”

Most noticeable to many was that he avoided terse political language. He talked about people and their desires, and spoke less about the party, and the tenets of his ideological bent. (This has all changed now.)

Party Congresses can indeed deliver surprises. Will this one? Although it may be pointless to live in the past, it can be thought-provoking to use it as a reference point for the present and future.

As Xi Jinping takes center stage at the 20th Party Congress set to begin in Beijing on October 16, one wonders if the catastrophes which he has created, and for which he is therefore responsible, could have any major effect on his chances of being chosen for an unprecedented third consecutive term as party leader.

Even in autocracies, candidates for office have to prove their capability to improve the lives of their people, not just their durability of power through political machinations and purges of competing contenders. People need to have reasons not to overthrow their government.

Xi has been personally responsible for detention programs in Xinjiang that have drawn not only the usual level of international condemnation of China’s human rights abuses, but also a designation from both the U.S. and the U.K. that China is a purveyor of “genocide.” Xi has overseen the shredding of the Basic Law that was meant to govern Hong Kong for 50 years after its 1997 handover back to China.

As if that were not enough, Xi has handled trade issues with the United States in such a way that a Republican president slapped 25 percent tariffs on a whole swathe of Chinese goods, and a Democratic president has so far kept them. It is telling that Donald Trump and Joe Biden could not be farther apart in the polarized U.S. political environment, and yet they find common ground in challenging Chinese trade policies.

Nations around the world are pushing back against exploitative practices associated with Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and much of the world believes that COVID-19 originated in China, despite Beijing’s frantic efforts to peddle conspiracy theories otherwise. Xi has called Vladimir Putin his “best friend” many times over many years, tying his personal credibility to arguably the most loathed man in the world for his murderous aggression in Ukraine.

How does Xi survive this?

He survives because many of the issues that to the international community seem impossible for Xi to overcome are of little widespread interest in China. Few Chinese have sympathy with the Uyghurs; they are told by the Chinese government that the Uyghurs are terrorists and that measures to control them are for the public safety. Most Chinese believe that.

Trade issues and tariffs are put down to jealousy and fear over China’s rise. Complaints over BRI projects are seen as unjust, when China has been so generous. Hong Kong’s complaints fall on deaf ears at best. Why should mainland Chinese take the part of Hong Kong Chinese who have made it clear that those from the mainland are less than welcome in Hong Kong?

And as for Putin, many Chinese believe he was pushed into a corner by the Western alliances, and all he did was come out fighting.

Xi’s primary vulnerability is his zero-COVID policy, which has locked down tens of millions of people, and which has driven the Chinese economy into the ground. If “all politics are local” in the sense that people care most about the political issues that impact them personally, then none could be more local than the policy that has intermittently deprived Chinese citizens of their liberty and prosperity. All of the other reasons for Xi’s political demise pale in comparison, if one is Chinese living in China right now.

Many China watchers would like to see the biggest of all October surprises. Wishful thinking among many – including many in China – hopes for Xi to be deprived of a third term. But it is not likely.

Going back to that slate of candidates that Jiang Zemin finagled onto the Politburo Standing Committee 10 years ago, there is one name outside of that roster that Jiang had already put his stamp on. Had it not been for Jiang’s nod, Xi himself might well have never achieved the top spot. Jiang identified Xi early on as a likely candidate for the ultimate leadership spots. A year after the 2012 Party Congress, Jiang even went so far as to praise Xi to Henry Kissinger.

Jiang told the former U.S. secretary of state, ”Recently, there were terrorist attacks in Xinjiang. Xi Jinping made determined decisions and swiftly put the situation under control.”

“Xi Jinping is a very capable and talented state leader,” Jiang told Kissinger.

Ten years after Jiang played kingmaker at the 2012 Party Congress, the “talented state leader” that Jiang underwrote is still at the top of the Chinese power structure. And Jiang, whatever his health may now be, is still with us, too. Jiang himself, now 96 years old, may no longer be able to directly influence the state of Chinese politics, but his former proteges can, and do. Whatever surprises may come out of the 20th Party Congress, the replacement of Xi Jinping is not likely to be one of them.