Nearly a decade after its launch, the Belt and Road Initiative – what was once nicknamed the “project of the century” – is slowly vanishing from Chinese leaders’ speeches. But the Chinese narrative about developing the world hasn’t disappeared; it just mutated toward a new initiative: the Global Development Initiative.

The Belt and Road Initiative has been China’s main branding strategy for its foreign policy over the past decade, and it was systematically and frenetically associated with Xi Jinping. But actually, Xi has been among the leaders who have used the term the least in their speeches as of late. The official name of “Belt and Road Initiative” ceased to really exist in Xi Jinping’s speeches in 2022, at least in the English versions, published for international audiences. Apart from the moments when he talks about “advancing high quality Belt and Road cooperation,” the BRI is fading away from Xi’s most important speeches, such as those given at the Boao Forum, BRICS, or the United Nations.

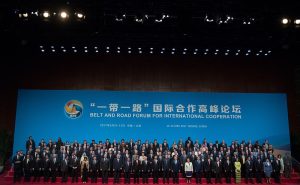

The BRI is not only disappearing from Xi’s speeches, but also from Xi’s agenda. While in 2017 and 2019, Xi was using the Belt and Road Forum to welcome leaders from all around the world to Beijing, these past few years, the BRI didn’t have a presidential forum. Instead, Foreign Minister Wang Yi was the Chinese leader in charge of hosting an “Advisory Council of The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation” in 2021. Xi basically delegated the Belt and Road Forum to Wang.

Out of 80 speeches by Chinese leaders published in English on the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China between 2021-2022, 44 speeches made a reference to the BRI, 22 of which only referred to it as “high quality Belt and Road cooperation,” a “green Belt and Road” or “Belt and Road cooperation.” This new BRI language architecture, “Belt and Road cooperation,” is a red flag about the future of the BRI. While in Chinese yi dai yi lu (literally “One Belt, One Road”) has maintained its position as the name for the Belt and Road Initiative, in English, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is now translating this Chinese name with syntagms such as “cooperation” or “partnership,” despite the fact that in the past, the Chinese government was insistent on its branding as the be the “Belt and Road Initiative,” and heavily discouraged the idea of the Belt and Road being associated with words like “strategy,” “project,” “plan” or other concepts. China seems to be changing its narrative about the Belt and Road for foreign audiences, migrating in English from “initiative” to “cooperation” – possibly because “cooperation” sounds more friendly, while “initiative” can be read as suggesting a top-down geopolitical plan.

Xi is not the only leader transitioning from the Belt and Road Initiative to “Belt and Road cooperation” – so has Wang Yi, the minister of foreign affairs, the last promotor of the BRI in 2021 and 2022. Wang wasn’t only the host of the last Belt and Road “forum” in 2021, but also the Chinese leader who promoted the BRI the most in his speeches, in an era when the BRI is fading away.

Despite this course, the ideas around the BRI are not disappearing. Instead, they are mutating toward a new narrative: the Global Development Initiative (GDI). Launched during Xi Jinping’s speech at the U.N. General Assembly in September 2021, the Global Development Initiative is as vague as the BRI used to be. It talks about promoting development in parallel with the U.N. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, by improving people’s lives, helping developing countries, driving innovation and being a link between people and nature. While the Global Development Initiative aims to be a greener, high-quality focused, better BRI, in reality it is just another slogan that fits China’s needs.

Thus, after the launch of the Global Development Initiative, the fate of the BRI has become even more unclear. Going back to the speeches, we see that since the launch of the GDI, there have been 28 mentions of the Global Development Initiative and only 25 of the Belt and Road, out of which 16 only mentioned “high quality Belt and Road cooperation.” The picture is even worse when we look at Xi’s speeches. He mentioned the GDI in 14 of his 15 speeches, but brought up the BRI only eight times and when he did, he used the syntagm “high quality Belt and Road cooperation.” In the last two months, the BRI vanished from Xi’s speeches, although he had an entire speech about “Forging High-quality Partnership For a New Era of Global Development” in June 2022. In that address, Xi never mentioned the BRI, but he relaunched the GDI brand and talked about development, South-South Cooperation, knowledge sharing, and helping other countries.

Why is the “Belt and Road Initiative” becoming just “Belt and Road cooperation” in official discourse, and why is the narrative around the BRI being transferred to the Global Development Initiative?

The BRI’s image has been affected very much over the past five years by accusations of debt traps, colonialism, ecological issues, and poor standards. Instead of fighting to erase those labels and to finally define the scope and purposes of the BRI, China came up with a “mini-me” BRI. The Global Development Initiative is thus the BRI in disguise, an old initiative that wants to look new, while also remaining vaguely defined.

Just like the idea of the Silk Road in 2012-2013, the “global development” narrative was omnipresent in Xi’s speeches even before the initiative was officially launched. Moreover, in January 2022, more than 50 countries expressed their interest to join a Group of Friends of the GDI, which was created at the United Nations, while over 100 countries expressed their support for the initiative. If that gives you déjà vu, it’s for good reason: The BRI’s main advertising narrative was built around the big number of countries that joined the initiative through MoUs and the amount of money the BRI planned to invest, part of which had been already pre-announced but was rebranded.

Speaking of money, in June 2022, Xi Jinping announced the renaming of a $4 billion Global Development and South-South Cooperation Fund. Déjà vu again: The idea is quite similar to the Silk Road Fund, Xi’s financial proposal for the BRI.

But China is emphasizing that it doesn’t want to replace the BRI with the GDI. As Wang said, the GDI and BRI are “‘twin engines’ to enhance cooperation in traditional areas and foster new highlights.” According to Wang, the GDI “will form synergy with other initiatives including the Belt and Road Initiative, Agenda 2063 of the African Union, and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development.”

But Chinese leaders’ words and actions give the opposite impression. The BRI has slipped into a latent state, while the GDI is amassing more and more space inside their speeches and in China’s public narrative. While the GDI’s increasing presence in Chinese leaders’ speeches may be part of the GDI promotion strategy, no new or old initiative can replace or reproduce the impact of the BRI on the global arena. Why? Because, from a PR point of view, the BRI was superior to the GDI and other Western initiatives that were proposed, as it was built on the myth, narrative, enthusiasm, and dreams throughout the world, including in the West, of rebuilding the Silk Road. This brand initially helped increase China’s soft power and international appeal.

Not only did the BRI have a historical resonance through its Silk Road association, but even though the GDI is a new, better planned initiative, it lacked the original enthusiastic response the BRI sparked in the West (which has now largely been forgotten, replaced by negative narratives), which helped it become an international name, a brand recognized all over the world. Almost nobody speaks about the GDI; nobody is elated by dreams of what the initiative can accomplish, as Western media once were with the BRI.

It matters that in this separating decade, China’s image itself has deteriorated, affecting any new initiative it proposes. Without a great reception, many of these ideas will remain just a name. That is why China shouldn’t give up on the BRI brand, but it should better articulate its goals and future actions in a way that won’t be perceived as harmful by other countries and entities such as the United States, the European Union, Japan, or India.

While the BRI was downgraded due to the multitude of criticism that it has received over the past years, it is not dead and won’t easily disappear, as it should mainly be perceived as China’s foreign policy branding strategy. And while the Global Development Initiative becomes the new trending term in Chinese leaders’ speeches, it has already proved that it doesn’t have the charm of the Belt and Road Initiative.