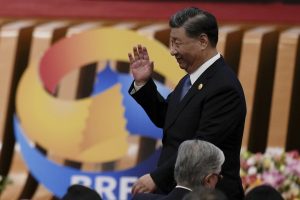

China hosted the third edition of the Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in Beijing on October 17 and 18. The forum, which also served as a celebration of the Belt and Road Initiative’s 10th anniversary, was a useful window into global perceptions of the initiative, as evidenced by which world leaders attended. But equally important, it provided a platform for China to explain its own take on the BRI, including the future of the project.

Since the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and “Maritime Silk Road” were first launched in 2013, the main criticism has been the vagueness of these ideas, which are now synthesized into the BRI. In the early days, anything and everything could be branded as a “BRI” project by the Chinese companies involved. Even today, there is confusion over what makes a project part of the BRI – see, for example, the public disagreement between China and Nepal over whether Pokhara Airport counts.

In the public imagination, the BRI’s image is largely tied up in hard infrastructure projects – roads, railways, airports, ports, etc. That’s likely because these sorts of projects are the most expensive, and so attract the biggest headlines. But as analysis from AidData has shown, in terms of project numbers, areas like education and health saw as many projects as the headline-grabbing transportation and energy deals. Meanwhile, despite China’s reputation for funding mega-billion “white elephant” projects, the median value of Chinese development projects from 2000 to 2017 was just $8 million.

Both the State Council’s white paper on the Belt and Road Initiative and Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at the BRF attempted to emphasize that the BRI is more than the hard infrastructure it is best known for. “Belt and Road cooperation has expanded from physical connectivity to institutional connectivity,” Xi declared. Even in the realm of “physical connectivity,” the digital sector has taken a place of pride, with the BRI “covering the land, the ocean, the sky, and the internet,” as Xi put it.

Much of what is emphasized in the white paper, and Xi’s keynote address, is an implicit response to criticisms that the Belt and Road is environmentally damaging, economically coercive, and promotes corruption through its lack of transparency. In short, China is attempting to overhaul the BRI’s image.

The white paper, for example, stressed the BRI’s commitment to “open, green, and clean cooperation,” while Xi made sure to note the “hydro, wind, and solar energy based power plants,” being built under the Belt and Road (notably, he avoided mentioning the more contentious issue of Chinese funding for coal power projects overseas).

There’s also a new focus in Chinese rhetoric on promoting host country agency, summed up in the mantra “planning together, building together, and benefiting together.” It’s an effort to combat the narrative that BRI projects directly benefit China, whether by giving Beijing access to key infrastructure or saddling other countries heavy debt loads. As the quip goes, in Beijing’s much-vaunted “win-win cooperation,” China wins twice.

In response, China wants to emphasize that host countries set the agenda for BRI cooperation. As the white paper put it, “The BRI was founded on the principles of extensive consultation, joint contribution and shared benefits.” (Of course, given the lack of transparency and autocratic governments in many BRI member countries, government elites wanting a specific project does not mean it’s actually good for the people.)

The BRI is getting a rebrand, but not entirely losing its hard infrastructure roots. Xi noted that China will continue to fund basic infrastructure like roads, railways, and ports, in particular pledging to “speed up high-quality development of the China-Europe Railway Express” and “participate in the trans-Caspian international transportation corridor.” And in an effort to combat the narrative that the BRI has been mothballed amid a sharp decline in Chinese funding, Xi committed new money toward such projects.

“The China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China will each set up a RMB 350 billion financing window. An additional RMB 80 billion will be injected into the Silk Road Fund,” Xi declared. Altogether, that amounts to over $100 billion in new funding (although, if China keeps to past precedent, much of it will likely be loans).

Moving beyond infrastructure, Xi pledged to advance trade cooperation along the BRI, including free trade agreements. He also promised to further open China’s markets, notably by “remov[ing] all restrictions on foreign investment access in the manufacturing sector.”

Topics like infrastructure, market access, and free trade were all highlighted at the first and second Belt and Road Forums as well. But there are some new developments worth paying attention to.

First, Xi made least a rhetorical commitment to increase “integrity” in Belt and Road projects, which could be read as an efforts to weed out corruption and combat the lack of transparency that plagues Chinese investment deals. New “High Level Principles on Belt and Road Integrity Building” and an “Integrity and Compliance Evaluation System” for companies taking part in BRI projects will be forthcoming. These have yet to be released, so we’ll have to reserve judgment for now.

In addition, China is leaning hard into the “Digital Silk Road” subsection of the BRI, with a focus on science and technology, innovation, and e-commerce. One of the most notable announcements made at the Forum was China’s launch of the “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Global Governance Initiative.” Beijing has already been experimenting with AI regulation at home; now it is hoping to shape the global rules and norms for this cutting-edge technology.

The “core components” of the initiatives include calls for a “testing and assessment system” for AI risk levels; “AI governance frameworks, norms and standards based on broad consensus”; and the creation of a new international institution to govern AI. Amid these proposals, China also included a call to “oppose drawing ideological lines or forming exclusive groups to obstruct other countries from developing AI” – a reference to the ever-tightening web of U.S. sanctions and exports controls, explicitly designed to hamstring China’s AI sector. Any country signing on to the AI Global Governance Initiative will thus be taking a position against the U.S. tech restrictions on China.

That Xi chose the BRF as the launching pad for the AI Global Governance Initiative shows how much the BRI has changed since its initial launch. The Digital Silk Road was still in an embryonic stage when Xi gave his keynote speech at the first Belt and Road Forum in 2017. AI, e-commerce, and science and technology innovation only merited one brief mention each as part of laundry lists of areas of interest. Compare that to the concrete proposals laid out this year.

The final takeaway is that the BRF is here to stay. China will continue to host the event, although Xi was mum on a possible timeline (the BRF once seemed to be headed for a biennial schedule, being held in 2017 and 2019 before the pandemic disruptions derailed it). In fact, China is even going to “establish a secretariat for the forum,” Xi declared.

It’s still not entirely clear how the BRI fits into the Global Development Initiative that was launched in 2021. Indeed, before this 10th anniversary year for the BRI, the GDI seemed to be pushing the Belt and Road to the back burner. Xi’s keynote, however, made clear that China is not losing interest in the BRI, even if it is changing the contents behind the name.