Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has produced two considerably different reactions from Beijing and Warsaw. China has been reluctant to condemn Russia’s aggression, while Poland has been at the forefront of backing Kyiv. How has the war in Poland’s immediate neighborhood shifted its relations with China, Poland’s largest trading partner in Asia?

China-Poland Ties Before the Russia-Ukraine War

First of all, both countries are of strategic importance for each other. Poland signed a Memorandum of Understanding on cooperation within the Belt and Road Initiative framework with China in 2015. One year later, the two nations elevated their bilateral ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” a symbol of diplomatic proximity that China shares with important partners such as France and Brazil.

Economically, Poland is China’s largest trading partner among the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries and its seventh largest trading partner among the EU member states. Also, Poland is a critical hub for the BRI and the 17+1 Initiative. Currently, the logistic hub in Malszewice located on the Polish-Belarusian border is responsible for servicing 90 percent of railway cargo exports from China to the EU; the seaports in Gdansk and Gdynia serve as a gateway for furthering Chinese products to Scandinavian countries. Recent investments in logistic hubs in the region seek to promote this trade route.

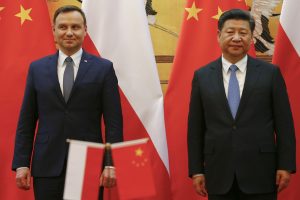

For Warsaw, conversely, China functions as a source of political leverage and an economic alternative that enables Poland to push back against the liberal intrusiveness of the EU. In economic terms, China was the second largest source of Polish imports in 2020, accounting for roughly 14.6 percent, and is its largest trading partner in Asia. In 2021, in a symbolic move to improve bilateral relations the Polish Ministry of Finance issued renminbi-denominated bonds in China. Prior to the outbreak of the Ukraine War, President Andrzej Duda participated in the Opening Ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics amid the boycott of the event by Western countries.

How Has the War Impacted Bilateral Relations?

Not only has Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered international reactions toward the parties directly involved, but it has also led to engagement or disengagement between third parties – in this case, China and Poland.

Duda’s visit to Beijing for the Winter Olympics’ Opening Ceremony marked a direct interaction at the highest level between the two countries just before the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine. According to Jakub Kumoch, Polish secretary of state and head of the International Policy Bureau, during his meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Duda explained the perspective of Central European countries, and warned his Chinese host that a war between Russia and Ukraine would disrupt transportation routes, which would not be in Beijing’s interest. This detail has been mostly left out of mainstream media coverage, where discussion mainly centered on the possible shift of Poland’s foreign policy orientation.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Kumoch avowed in April that Warsaw would reaffirm its position to Beijing, and hoped that China would step in and mediate the conflict. While he did not expect China to shift its anti-U.S. and pro-Kremlin rhetoric, Kumoch took note of China’s pragmatism in handling international affairs and expected to see deeds rather than words. In July, Xi initiated a one-hour phone call with Duda in which the pair discussed the unfolding crisis in Ukraine. The Polish president indicated the adverse impact of Russia’s invasion on regional security and international trade, including that with China. In addition, he suggested to the Chinese leader that Beijing could assume a more constructive role in preventing Moscow from causing a global food crisis.

If bilateral relations are are still marked by regular communication at the highest level, on the lower working level the reality raises questions about the state of the China-Poland “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

Four months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki published an opinion piece in which he warned against the threat of China taking advantage of the geopolitical passiveness of the Western world to seize global assets and outcompete Europe and the United States. At the Poland-China Intergovernmental Committee in June, Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau called on “all nations that respect the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the strongest terms,” alluding to the fact that Beijing was not willing to condemn Putin’s aggression. Most recently, China again abstained from voting in the U.N. Security Council on Russia’s annexation of so-called “people’s republics” in occupied Ukrainian territory. In May, the Polish Foreign Ministry even refused to meet with the Chinese delegation that was at the time on a diplomatic tour in CEE nations reevaluating the region’s attitude toward the 17+1 Initiative.

Aside from the divergent positions of the two countries, China has allegedly projected its pro-Kremlin propaganda and anti-NATO discourse in the Polish digital sphere, both through diplomatic channels and via China Radio International. To complicate the issue further, Chinese media have cited Moscow’s fake news for the purpose of domestic propaganda, with some even suggesting that Polish soldiers would be sent to defend Ukraine. Later, the Polish Defense Ministry described this as a product of one of Russia’s disinformation campaigns. Such events in cyberspace are not going unnoticed in Warsaw and may negatively impact the already strained relationship between Beijing and Poland.

What Are the Implications for China-Poland Relations?

For Poland, the Russia-Ukraine War has brought the presidency’s and the government’s views of China into closer alignment. Duda used to adopt a less hawkish approach toward Beijing than his government, for he reportedly aspires to a position at the United Nations after the elections and hence would need to count on Beijing’s support or, at least, acquiescence. That partially explains why he has never condemned China for human rights violations, and disagreed with his government’s hawkish stance. Before the 17+1 Summit in February 2021, the Polish Foreign Ministry had advised Duda to downgrade the level of representation and not attend the virtual meeting with Xi Jinping personally. The president dismissed the recommendation, arguing that “no important event concerning Central and Eastern Europe can take place without the presence of Poland.” Nevertheless, the war in Ukraine may significantly align positions from the head of state and the government, leading to a more united position vis-à-vis Beijing.

Second, one cannot ignore a shift of views about Beijing in the broader region when analyzing the evolution of China-Poland relations. In August, Estonia and Latvia withdrew from the 17+1 format, after Lithuania’s withdrawal last year; Czechia is considering following suit. Poland and Romania, together with several other CEE countries, have banned Huawei from their national 5G rollouts.

In this sense, it would be necessary for Beijing to ameliorate the deteriorating relationship with Poland, especially as the pro-Beijing Duda will have to leave office once he finishes his second term. As Poland is a strategic CEE partner for Beijing, China may double its diplomatic efforts by reassuring Warsaw about its position and by showing more assertiveness in mediating the war. For example, despite the ongoing war, China pledged to continue to make Poland the gateway to Europe. Also, Beijing has proposed aid for Ukrainian refugees in Poland.

After the phone call between Duda and Xi in late July, China’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement in which it referred to Poland as its “prioritized cooperation partner in Europe.” Moreover, commenting on Russia’s aggression, Chinese Ambassador to Warsaw Sun Linjiang published an op-ed in which he recognized the threats to global peace and called for building a “community and great family” based on three pillars: bilateral relations, cooperation with CEE nations, and cooperation with the EU. On the sidelines of a United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York last month, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his Polish counterpart Zbigniew Rau that “an expanded and protracted Ukraine crisis is not in the interests of all parties.”

Third, Poland’s military reliance on NATO and Washington makes its alliance with the United States extremely important, and this has been deeply accentuated by the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine. Poland’s prominent alignment with Washington, intensified by Russia’s aggression, may have implications for bilateral ties with an increasingly expansionist and assertive Beijing. China’s growing military assertiveness over Taiwan may ultimately compel Poland to choose a side, though so far the Polish government has not yet commented on tensions in the Taiwan Strait. Yet it is telling that, during his visit to Vilnius in September, Poland’s Rau criticized Beijing’s strong-arm measures against Lithuania and expressed disappointment over unresolved trade issues with China. An Inter-Parliamentary Amity Association between Taiwan and Poland has been recently created, which serves as an important platform for exchange between the two legislatures. Additionally, Taiwan has offered aid to help settle Ukrainian refugees in Poland, which may have driven Beijing to offer assistance as well.

Last but not least, although the Russia-Ukraine War may have exposed areas of contention areas in Sino-Polish relations, there still exist two stabilizing factors. First, Beijing will continue to be seen by Warsaw as an alternative partner with which to push back against intrusive policies from Brussels, especially against the backdrop of the European Commission’s suspension of over 35 billion euros of COVID-19 relief funds to Poland. Second, Polish agribusiness and food exporters are also concerned about the negative repercussions of the government taking a tougher stance toward China, and would prefer to see a more amicable and pragmatic posture.