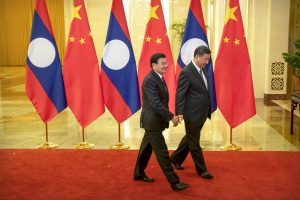

In late 2017, Xi Jinping made a state visit to a strategically important neighbor in Southeast Asia. His trip to Laos occurred immediately after the 19th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress had elected him their leader for a second term.

On the final day of the trip, state-run media released a video of a gathering at which the Chinese president met his old schoolmates, the Pholsenas. Xi teased Sommano Pholsena, his contemporary at the Beijing Bayi School in the early 1960s. “At that time he was a chubby, lovely, and strong boy,” he said of the former vice general manager of the state power utility Électricité du Laos, as Sommano’s siblings looked on with amusement. Sommad Pholsena, a member of the National Assembly, told Xi that the family was grateful for his words about their late father, a former foreign minister of Laos. An emotional Sommano wiped away tears.

Xi’s outreach to the Pholsenas was more than just a friendly visit with old schoolmates. The encounter provided a fleeting glimpse into how China’s leader deployed soft power to pursue his signature foreign policy priority, the Belt and Road Initiative. The 19th CCP Congress had recently added the infrastructure development plan to the party constitution, and the president had unveiled a bold foreign policy that aimed to make it a reality. Chinese media called the new approach “Xiplomacy.”

Laos is central to China’s Belt and Road ambitions in Southeast Asia. The China-Laos Railway is the first link in a proposed international rail network connecting Southwest China with seven countries in the region. At the inauguration of the Lao section of the 1,035-kilometer Kunming to Vientiane line last December, Xi called the railway a landmark project. Sommad Pholsena, a former transport minister, told People’s Daily, “China wasn’t the first country that said it would help Laos build railways, but it was the only one that actually did it.”

The mega project came with a $6 billion price tag, Laos’ portion of which was covered primarily by loans from China. The country’s public debt now stands at $14.5 billion, of which half is owed to China. At the time of Xi’s visit in 2017, the economy was growing at 7 percent, and Laos appeared well-positioned to meet its debt obligations. Then the pandemic hit. When the Chinese president inaugurated the railway last year, the Vientiane Times ran a story with the headline: “Govt in need of massive financial support.” By June, Laos was facing a full-blown economic crisis with record inflation and dwindling foreign exchange reserves. Moody’s severely downgraded the credit rating, suggesting that the country was at risk of default.

Could Laos default? Experts think that’s unlikely. Financial life rafts, such as refinancing, credit injections, or equity infusions, are the more realistic path forward. Last March, China Southern Power Grid acquired a majority stake in Électricité du Laos for 25 years. Although Laos temporarily ceded control of a national asset, the deal would inject $2 billion into the state-owned electricity company. China “will not let Laos default,” wrote Toshiro Nishizawa, a professor at The University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Public Policy and fiscal advisor to the Laos government.

Laos is part of a socialist ecosystem in Asia that transcends borders. Xi first met the Pholsenas at a Beijing elementary school set up to educate young communists. Founded in 1947 by a top commander of the People’s Liberation Army, the Beijing Bayi School was known as the “cradle of leaders.” The students came from well-connected families. Xi’s father was one of China’s revolutionary leaders and Mao Zedong’s compatriot. Quinim Pholsena forged close ties with Mao and his lieutenants on his many visits to China as foreign minister of Laos.

The early 1960s were bleak times for Xi’s family and the Pholsenas. Xi Zhongxun, vice premier of China under Zhou Enlai, was accused of anti-party activities and stripped of all leadership positions in 1962. Xi’s half-sister was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and reportedly took her own life. In early 1963, Quinim Pholsena was assassinated by one of his bodyguards for his communist leanings. He was ideologically aligned with the Pathet Lao, the communist movement that came to power in 1975.

In 2010, the Beijing Bayi schoolmates reconnected in Vientiane under happier circumstances. Xi was visiting Laos as vice president of China. “He told us that he . . . was delighted to see us again after half a century. He remembered what kind of clothes we wore to school,” recalled Sommad. Their longstanding association, he explained, was a microcosm of relations between two countries that were “forever good neighbors, good friends, good comrades and good partners.”

Xi’s friendship with the Pholsenas was also good foreign policy. Selection for leadership positions in the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party often involves “horse-trading” between influential families. The Pholsenas fared well with two family members in the party’s 11th Central Committee. Khemmani Pholsena is a top aide to the new president. Her promotion was a sign the government intended to leverage the China connection.

As old friends of China, the Pholsenas did their part to burnish Xi’s credentials as a global statesman on the eve of China’s 20th Party Congress. In a video entitled “Xi in my eyes,” Sommano called his schoolmate “charismatic.” He commended China for “sharing development opportunities with the world.” Sommad admitted he was a fan of Xi’s books on governance and welcomed the Chinese president’s new initiative on security.

Earlier this year, Xi outlined his vision for a “more just” world order. China’s pitch for a new global security platform suggests that Xi “is primed to accelerate his push for a greater international leadership role,” noted John S. Van Oudenaren, editor of the Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief.

The fourth volume of “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China” was released this summer. In this collection of Xi’s speeches, China’s leader is surprisingly down to earth. “Governing a big country is as delicate as frying a small fish,” wrote China’s president. Xi’s ability to connect with an audience may be one of his most underrated talents.