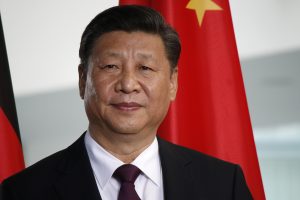

Xi Jinping, the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since 2012, is widely expected to sail into a third five-year term at this month’s 20th Party Congress. This will make him the longest-serving party chief since founding leader Mao Zedong. It will also represent a risky departure from a system of collective leadership and orderly succession that had given the Chinese regime an important advantage over its less stable authoritarian peers.

Paradoxically, the party’s renewed commitment to its “core leader” is coming at a time when the Chinese government faces a daunting array of foreign and domestic challenges, most of which have been prodigiously exacerbated by Xi’s own policy choices. In effect, the CCP appears to be succumbing to the authoritarian curse of one-man rule, binding itself to the flawed judgment of a single personality and potentially dragging the entire country down with it.

A Bet on Rigidity

Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, served as CCP leader and state president for 10 years. Hu’s predecessor, Jiang Zemin, also served as state president for 10 years, though his tenure as CCP chief lasted slightly longer, from 1989 to 2002. The procedural norm of limited terms was first established by Deng Xiaoping, who relinquished his state and party posts after less than 10 years in the 1980s. At each party congress during those decades, a new crop of rising stars was elevated into the Central Committee, the Politburo, and the elite Politburo Standing Committee, signaling possible lines of succession for the years to come.

The system was far from democratic, as ordinary citizens had no input on these opaque intraparty decisions. But it provided stability after the turmoil among elites that surrounded the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, as well as a crucial degree of flexibility that allowed the CCP to change personnel and policies in response to changing conditions.

In 2012, however, the party turned to Xi Jinping, who was tasked with restoring internal discipline after an unprecedented scandal centered on the ambitious politicking of Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai. Xi fulfilled this mandate by eliminating Bo and his allies through a series of corruption charges and show trials, but he also went much further, concentrating power over policymaking in his own hands, sidelining potential successors, fostering a cult of personality, and formally installing himself as the CCP’s ideological wellspring. At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, “Xi Jinping Thought” was written into the CCP constitution.

Dissenting party officials and 1.4 billion citizens now find themselves all but powerless as their iron-fisted leader steers them into increasingly dangerous waters.

From Bad to Worse

If the CCP regime spent most of the last few decades building up its economic and political capital after the nadir of Mao’s totalitarian rule, Xi seems determined to squander whatever has been accumulated.

Within China, his administration has reduced even the limited space his predecessors tolerated for civil society activity, rule-of-law reforms, and online discussion. Over the past decade, the country’s score in Freedom in the World, Freedom House’s flagship assessment of political rights and civil liberties, has dropped from 17 to a mere 9 on a 100-point scale. More recently, the CCP under Xi has demolished political autonomy and human rights in Hong Kong, orchestrated atrocity crimes against millions of Muslims in Xinjiang, and suppressed calls for women’s rights even as it urges women to reverse China’s population decline by having more children.

On the economic front, Xi’s government has imposed harsh and politicized regulations meant to rein in the private sector, mismanaged a real-estate crisis that stems from years of official efforts to prop up growth through debt-backed construction and has now cost many citizens their savings, and clung doggedly to draconian COVID-19 restrictions that are further harming growth and driving a crescendo of public outrage.

Internationally, Xi has encouraged an aggressive brand of “wolf warrior” diplomacy, in which Chinese envoys scold and attack local critics and demand deference to China’s superpower status. He has flexed the country’s military muscle along the border with India, in the South China Sea, and in the Taiwan Strait, alarming China’s neighbors and prompting them to seek closer ties with Washington and one another. And he has pushed ill-conceived and corruption-laden infrastructure projects on every continent through the Belt and Road Initiative, co-opting some local leaders but alienating many citizens as the financial, environmental, and national security costs of the deals become clear.

It is increasingly evident that Xi’s policies are backfiring across the board. A recent Freedom House report on Beijing’s global media influence efforts found that public opinion toward China’s regime has actually grown worse in recent years, even as the CCP devotes enormous resources to international propaganda, censorship, and disinformation. Instances of active pushback against CCP influence – by journalists, civic groups, or governments – were found in all 30 countries covered in the study. Meanwhile, democratic governments and international businesses are working to divert their supply chains away from China, undermining its vital manufacturing sector.

Signs of domestic discontent are substantial as well, despite intensifying repression. A forthcoming Freedom House project, China Dissent Monitor (CDM), has so far documented some 600 protests and other instances of dissent by Chinese citizens between June and September 2022. A third of the cases are linked to failed or delayed housing projects across the country. CDM has also tracked more than three dozen separate protests against strict pandemic rules, including street demonstrations with hundreds of participants and online movements with hundreds of thousands of posts.

Locked Into Failure

Xi is far from alone in clinging to power while driving his country toward ruin. All authoritarian rulers suppress dissent, eventually losing access to good advice and accurate information. And in the absence of democratic elections, they must base their legitimacy on an aura of infallible success, meaning any course correction or admission of error is fraught with danger.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose rule has grown steadily more oppressive since he took power in 2003, frankly acknowledged the challenge of policy reversals during a recent interview about Vladimir Putin’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine: “No leader in the aftermath would say that it was a mistake. Nobody will say, yes, I made a mistake… The leaders, when they take a path, they will find it very difficult to go back.”

However much they insist on their infallibility, Xi and other authoritarians who seek a third, fourth, or fifth term in office are effectively confessing to at least one enormous failure: by centralizing authority, gutting independent institutions, and eliminating potential successors, they have built regimes that cannot survive without them, raising the risk of catastrophic instability when they inevitably leave the scene. Yet as long as they prioritize personal self-interest over both elite and national interest and reject checks on their own misjudgment, their regimes may not be able to survive with them, either.