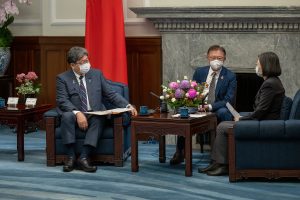

Last weekend, Hagiuda Koichi visited Taiwan and held a meeting with President Tsai Ing-wen. Hagiuda’s visit, from December 10 to 12, was watched closely, as he is the chair of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) Policy Research Council. This was the first time since 2003 that such a high-ranking member of LDP visited Taiwan.

During their meeting, Hagiuda and Tsai confirmed that Japan and Taiwan would increase security cooperation in response to China’s increasing military pressure on Taiwan. Tsai stated, “Together, we would like to promote peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region,” and Hagiuda responded, “Taiwan is an important partner, and we share fundamental values.”

Hagiuda spoke strongly to reporters after the meeting, saying, “We confirmed our basic stance that Japan and Taiwan will firmly protect the Taiwan Strait and that we will not allow the changing of the status quo by force.”

During the same visit, Hagiuda noted that in the face of China and North Korea’s increasing capabilities, he supported increasing Japan’s defense spending. Japan is currently set to increase defense spending from 1 percent of its GDP to 2 percent of its GDP within five years. One point on which Hagiuda may perhaps diverge from the Japanese government is that Haguida has an even greater sense of urgency, pushing for capabilities to be developed even faster than over a five-year period.

LDP members had generally refrained from visiting Taiwan out of consideration for China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan and strongly rebukes any interactions with the Taiwanese government. Although it is important to not lose sight of the international context – i.e., increasing tensions across the Taiwan Strait – an analysis published in Asahi argues that Haguida’s trip was as much about domestic politics. Asahi’s Kohei Morioka framed the visit as an attempt by Hagiuda to position himself as the heir to assassinated former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and take over Abe’s faction.

Abe was pro-Taiwan, and famously argued in November 2021 that “A Taiwan emergency is a Japanese emergency, and therefore an emergency for the Japan-U.S. alliance.” Other LDP politicians may attempt to copy Hagiuda’s tactics, including Seko Hiroshige, who is planning a visit to Taiwan before the end of the year.

While the Taiwan issue may be used to score political points within the Abe faction of the LDP, it is also an issue that is being addressed by the government with the gravity that it deserves. A draft of the new National Security Strategy shared with Yomiuri states, “Peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait are indispensable for peace, stability, and prosperity of the international community.” The draft also affirms that Taiwan is “an extremely important partner and friend with whom our country [Japan] shared fundamental values” and that Japan will “continue its efforts to deal with [cross-strait relations between China and Taiwan] based on the position that the related issues should be resolved peacefully.”

What’s next for Taiwan-Japan relations? What can Japan do to better stabilize the Taiwan Strait? One idea, put forward by Takahata Akio, director of Nippon Communications Foundation, is for Japan to have its own version of the United States’ Taiwan Relations Act. Such legislation would provide “a permanent legislative basis for practical Taipei-Tokyo relations.”

Takahata noted that Japan’s version of the Taiwan Relations Act should focus not just on defense issues, but address all aspects of Japan-Taiwan relations, including politics, economics, commerce, tourism, and cultural and human exchanges, so that China has less reason to oppose it. However, the most important part of this legislation would still be to “state clearly that the future of Taiwan must not be decided by anything other than peaceful means” and “commit [Japan] to a fundamental stance of resisting intimidation or any use of military force.”

A U.S.-Japan-Taiwan Track 2 dialogue convened by the Foreign Policy Research Institute also raised innovative suggestions and highlighted pressing challenges. Findings from the dialogue concluded that the United States, Japan, and Taiwan should increase investments in deterrence and defense readiness, and that the U.S. and Japan both need to develop better channels for military-to-military communication with Taiwan at the senior and middle levels. For Japan, this would mean reinterpreting or removing official restrictions.

There are two particularly important and often overlooked findings from the FPRI dialogue. First, there must be emphasis on the assurance side of deterrence, e.g., “signaling to China that Taiwan will not pursue de jure independence and the United States and others will refrain from recognizing Taiwan as an independent state, so long as China upholds its obligation to refrain from use of force and coercion.” Second, there’s a need for the U.S., Japan, and Taiwan “to address [their] domestic political foundations for resolve and resilience, primarily by communicating effectively to their respective publics the national security consequences of failing to deter conflict or defend Taiwan.”

As these suggestions indicate, there is much work to be done by Japan on the Taiwan issue if Japanese politicians are serious about stepping up. Hopefully Hagiuda’s visit was – and future LDP politicians’ visits will be – substantive and focused on how to make the changes necessary, and not just a thin cover for burnishing hawkish credentials back home.