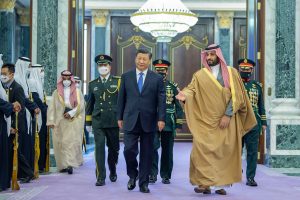

On December 7, Chinese President Xi Jinping, fresh off securing a third term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, chairman of the Central Military Commission, and effective paramount leader of the PRC, arrived in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for a three-day visit. He was met with substantial pomp and circumstance, complete with purple carpets, an airshow, a royal guard contingent, and ceremonial cannon fire. He was then feted with a lavish reception at Al Yamama Palace hosted by Mohammed bin Salman, crown prince and effective leader of the Kingdom.

The display was widely compared in the media to the reception granted to U.S. President Joe Biden when he visited Saudi Arabia in July, and was received by the governor of the Mecca region with considerably less fanfare.

Indeed, Xi’s visit has largely been viewed through the lens of Saudi-U.S. relations, particularly due to the residual tension between Washington and Riyadh over the decision of OPEC+ to raise the price of oil through a supply cut. The United States views this as effectively aiding the Russian war effort in Ukraine by increasing the flow of cash to Moscow’s war machine. Accordingly, international media decided that Xi’s visit “seeks to exploit Riyadh-Washington tensions,” comes “amid frayed ties with the US,” “steps on Washington’s toes,” and is the result of a policy “made in the US.” Others assert this is part of a wider Chinese strategy to promote “an alternative to the Western-led security order” and a “new scramble for the Gulf.”

But while relations with the United States are undoubtedly a factor in Saudi Arabia’s calculation, Xi’s visit is about far more than that. Sino-Saudi ties are both deeper, and more limited, than the current coverage would suggest.

A Deepening Relationship…

In the last decade, Sino-Saudi relations have increased considerably, leading to a deep partnership based primarily on heavy trade and investment in the oil and chemical industries. Saudi oil accounted for 18 percent of all Chinese oil imports in the first 10 months of 2022, reaching a total of 1.77 million barrels per day, making it China’s largest individual supplier of oil. Conversely, China is Saudi Arabia’s number one purchaser of chemicals and oil (buying 25 percent and 27 percent of all Saudi production, respectively) and number one trade partner. Bilateral trade reached approximately $87 billion in 2021, 95 percent of which consisted of oil, plastics, and other chemical products. Saudi Arabia also has considerable investments in and exclusive supply deals with Chinese oil refineries.

This week’s visit has come with a flurry of new MoUs and other agreements signed that seek to diversify and expand this partnership into new areas, although oil and chemicals will certainly remain the bedrock foundation of the partnership. Thirty-four bilateral agreements were announced on the first day of the visit, including with controversial telecommunication company Huawei, that will lay the foundation for Chinese investment in areas such as green energy, information technology, transportation, cloud services, medical industries, logistics, construction, and housing.

The immediate announcement of such a large number of agreements, along with the fact that rumors about Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia have been circulating since August, suggest that preparations began long before Biden’s own visit in July.

While these agreements are not binding, there is little reason to believe that China will not follow up on these commitments, as Saudi Arabia was the largest recipient of Chinese investment in 2022, and previous investments have been highly successful. This contrasts with Iran, where repeated efforts to increase investment have been announced, then failed to materialize due to pressure from the United States and the Gulf states, the collapse of the nuclear deal and potential for sanctions relief, and a lack of profitability.

…But a Limited Partnership

While the China-Saudi partnership has deepened in recent years, it also remains fundamentally limited. The main limiting factor is the inescapable fact that Saudi Arabia remains fully dependent on the United States for its security, and the U.S. Middle East strategy depends on close relations with Saudi Arabia.

Sino-Saudi bilateral weapons sales amounted to only $245 million between 2003 and 2021, compared to $17.85 billion between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia during the same period. While China has recently announced a much more substantial sale of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) worth $4 billion, more significant hardware like air-to-air missiles and fighter jets remain the exclusive domain of the United States. Both Chinese officials and scholars critical of China’s role in the Middle East have noted that the United States would likely intervene to prevent the sale of more substantial weapons, as it has done in the past.

Neither side seems interested in fundamentally changing this partnership, in spite of recent tensions. Biden pledged in July that the U.S. “will not walk away” from the Middle East and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Iran, and Russia, and it seems unlikely that the dispute over the price of oil will alter the balance of power.

This should come as no surprise, as China has shown little to no interest in replacing the United States as security hegemon in the Middle East. This is in part because China clearly benefits from such an arrangement, which provides a stable environment for trade and investment without the need to compete with Washington’s massive military presence in the region. More importantly, even if one believes that such pronouncements are a smokescreen for Chinese global ambitions, Beijing simply lacks the economic and military means to establish such a network, even if it wanted to. To date, China has established only one overseas military base in Djibouti, which does not seem to have caused too much friction with the United States, and despite rumors of plans to establish a second in the UAE, there is no evidence that this is true.

While China no doubt chafes at the fact that the critical Gulf shipping lanes, which they depend on for oil imports, remain under the security umbrella of the United States (and could therefore be shut down in the event of a conflict), it has thus far sought only to play a greater role in Middle East security issues and criticize U.S. unilateralism, not to replace the United States entirely.

More Than a ‘China Card’

Sino-Saudi relations do not occur in a vacuum. In addition to China, Saudi Arabia has also sought to increase investment in and attract investment from a variety of Asian countries that, unlike China, have a much less complicated relationship with the United States. For example, the Kingdom restored relations with Thailand in 2016, and seeks to use this as a springboard to invest throughout Southeast Asia. Riyadh has also recently pursued a $30 billion dollar investment deal with South Korea. Notably, both Thailand and South Korea are U.S. allies.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia has been seeking to diversify its economy and seek a wider variety of partners since at least 2016, when it first announced the Vision 2030 project, which seeks to reduce the Kingdom’s dependency on oil exports and attract investment from a wide variety of sources. More recently, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund pledged to invest $24 million in countries closer to home throughout the Middle East and North Africa region. In short, Saudi Arabia is seeking not only to bolster ties with China, but to diversify its diplomatic, economic, and military relations more generally.

China is also engaging with Saudi Arabia as part of a larger effort to engage with all the Gulf states, as well as Iran, which requires careful balancing and precludes China placing all of its eggs in one basket.

More than simply playing the “China card” against the United States, Sino-Saudi engagement is driven by a strong economic foundation and a desire on the part of both nations to diversify and globalize their economies. This is part of a larger program pursued by both to bolster domestic stability and government support, which is highly dependent on providing continuous economic growth. While Mohammed bin Salman may be looking entice the United States into providing greater support, he is also engaging China for its own sake, to further his own domestic political and economic goals.

Seen this way, the specter of rising Sino-Saudi relations, like the specter of a growing China-Iran relationship, appears to be more of a function of U.S. desires to contain, delay, and slow China’s growing economic engagement with the world, in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. Despite the deepening of these ties, the Saudis remain close allies to the United States, and the possibility of Beijing replacing Washington as Saudi Arabia’s most significant ally remains slim.