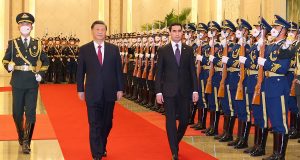

Turkmen President Sedar Berdimuhamedov paid a state visit to China from January 5 to 6, at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping. It was the first high-level exchange between China and a Central Asian country in the new year. During the visit, the two presidents announced the upgrading of the China-Turkmenistan relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership, a new height for bilateral relations.

In recent years, China has increased engagement with Central Asian states sharply, both bilaterally and multilaterally. Last year, Xi visited Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in his first trip abroad since the pandemic began; now the Turkmen president is the first Central Asian leader (and the second foreign leader overall) received by China in 2023. The frequent exchanges between the head of states reflect that China attaches greater importance to Central Asia, which has undertaken an ever more significant role in China’s neighborhood diplomacy, especially after the Russia-Ukraine war.

China has forged comprehensive strategic partnerships with all the Central Asian states. China established a comprehensive strategic partnership with Kazakhstan in 2011 and later elevated it to a permanent comprehensive strategic partnership, This was followed by Uzbekistan in 2016, Tajikistan in 2017, and Kyrgyzstan in 2018. Turkmenistan is the last country in Central Asia to develop such ties with China.

At the regional and multilateral level, China proposed the establishment of a China-Central Asia (C+C5) cooperation mechanism, a new format of multilateral cooperation between China and Central Asian countries outside the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). With the support of Turkmenistan and other Central Asian countries, the first “C+C5” summit is expected to be held this year.

At the same time, China has signed cooperation agreements under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with all the Central Asian states to strengthen synergy between the BRI and their own national development strategies. Physical connectivity such as cross-border railways, gas and oil cooperation, trade, and investment are crucial in the BRI agreements.

It is noteworthy that a cross-border railway was mentioned in the China-Turkmenistan talks, following on increased attention to the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway project, brought up by Xi during his visit to Uzbekistan last year. As Turkmenistan borders Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and the Caspian Sea, the China-Turkmenistan railway will be an extension to the CKU rail line. It’s hoped the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan (CKUT) railway becomes a reality in the coming years.

Running west to Iran and south to Afghanistan, the CKUT railway will be a Eurasian transportation artery and a main rail line connecting Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. Given ambitions for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to be expanded into Afghanistan, if the CKUT can also be extended to Afghanistan, a railway network would be established linking China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This is strategically significant to energy cooperation between China and Central Asian and South Asian countries, as well as the economic ties between them. On one hand, the cross-border rail line will make it easier to transport petroleum and natural gas, fostering more pipeline construction. Notably, China reached an oil exploitation deal with Afghanistan in recent days. On the other hand, the imbalance in trade between the countries along the line may also be redressed, considering the increased exports to China from Central and South Asia. The cross-border rail line could thereby inject political and economic vitality to China-Central Asia-South Asia trilateral relations.

At the same time, South Asia in particular has been one of the main arenas of terrorist attacks targeting Chinese workers and interests. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the wider region has witnessed waves of domestic protests and violence against governments, and leading to the ouster of incumbent ruling parties in some states such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Moreover, the economic depression and even economic crisis partially caused by the pandemic and the complex geological conditions in the area are also the main obstacles to the construction of cross-border railways in the region.

There are some difficulties for China to make the vision of a cross-border railway in Central and South Asia a reality. It’s worth bearing in mind that difficulties do not necessarily derail such projects. Despite unstable domestic politics and the great technical difficulties of building railways in the Himalayas, in December China initiated a feasibility study for the China-Nepal cross-border railway. Therefore, a long railway across China, Central Asia, and South Asia may still be feasible in the future, and it could substantially change both geopolitics and geoeconomics in the region.