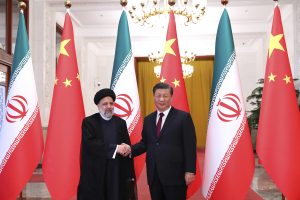

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s three-day visit to Beijing has revived China’s balancing act in the Persian Gulf after the setback that followed Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s trip to Saudi Arabia in December. Symbolically, Beijing has reassured Iran that it is a partner worth no less than Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. But little suggests that the economic breakthrough once again claimed by the Iranian authorities will eventually follow the umpteenth signature of tens of Memoranda of Understanding between the two countries.

In fact, the primary impediment to the implementation of the 25-year comprehensive strategic partnership China and Iran signed in 2021 continues to be the presence of U.S. secondary sanctions. Or, from a different perspective, the failure to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, colloquially known as the Iran nuclear deal) following then-U.S. President Donald Trump’s withdrawal in 2018.

In May 2022, I wrote that the Iran deal best serves China’s security interests in the Persian Gulf, and I still stand by that assessment. Yet, there is no doubt that Beijing has not done much to revive the agreement. Raisi’s visit to China came when the prospect of a return to the Iran deal or even for a JCPOA 2.0 is tenuous. Still, despite the agreement’s utterly comatose state, Xi reaffirmed China’s commitment to the swift implementation of the JCPOA.

“Judging from what President Xi said to the Iranian president in Beijing, I think China really wants to advance the JCPOA negotiations,” said Fan Hongda, a professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the Shanghai International Studies University and a leading Chinese expert on Iran. “Beijing does not want to see the Iran Deal abandoned.”

Indeed, according to the official readout, Xi reassured Raisi that “China will continue to take a constructive part in the negotiations on resuming the nuclear deal, support Iran in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests, and work for an early and proper settlement of the Iranian nuclear issue.”

Xi’s words are far from surprising. Since 2018, little has changed in China’s position on the JCPOA – a mix of calls for a return to the agreement and blaming the United States’ unilateralism while remaining on the sideline of the Vienna Talks. After Raisi’s trip to Beijing, the elephant in the room remains what Chinese officials have told their Iranian counterparts privately. The presence of Iran’s chief JCPOA negotiator, Ali Bagheri Kani, in the delegation that visited China, although not surprising given the scope of the visit, suggests an exchange of views more profound than the rather unimpressive public rhetoric.

Still, the reality is more nuanced. China appears comfortable enough with the status quo, not because it is the best option on the table – that would be a return to the JCPOA – but because, from Beijing’s perspective, it is sufficient to guarantee China’s core interest in the region. After all, even after Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran deal, the broader framework of the agreement has remained in place, guaranteeing minimal control over Iran’s nuclear escalation and keeping the parties engaged in negotiations.

Yes, Chinese investments in Iran have languished since 2018, demonstrating how critical the deal is to the future of Sino-Iranian relations. But the economic, financial, and political ties between Beijing and the GCC states are flourishing, unimpacted by the maritime tensions in the Persian Gulf. Xi’s trip to Saudi Arabia in December showed that despite a moribund JCPOA, China’s footprint in the region continues its seemingly unstoppable expansion, welcomed and cherished by its Arab partners.

In a global scenario where more significant issues fully engage Chinese diplomacy – the competition with the United States and the Russia-Ukraine War – the incentives to allocate precious diplomatic resources to play an active role in mediating between Iran and Washington are minimal, especially given that Beijing lacks the will and experience to take the lead in the talks for a JCPOA revival. Instead, China is more comfortable offering Iran an economic lifeline through undeclared oil imports, guaranteeing itself a source of cheap crude and avoiding the potential escalation risk of an economically cornered Islamic Republic. The result is a precarious equilibrium strictly hung on the status quo.

Then there is the principled position. In an editorial before Raisi’s visit, the Global Times framed Sino-Iranian relations as “anti-hegemony and anti-bullying,” a position shared by many Chinese experts. From the Chinese perspective, Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran deal and the imposition of sanctions are an example of U.S. unilateralism.

According to Professor Fan, “if fairness and justice can be talked about in the international community, it is indeed wrong for the United States to withdraw from the JCPOA unilaterally. Resuming full implementation of the JCPOA is also a [matter of] respect for international fairness and justice.”

For China, the party that needs to compromise after jeopardizing the JCPOA and being the “root cause of the current situation” is the United States, not Iran. Still, according to Fan, while the JCPOA remains the best option for China, “if the U.S. and Iran can reach a bilateral settlement outside of the JCPOA negotiations, then the current agreement will not matter so much. But can the two countries reconcile in a shorter period?”

Only the fear of the final collapse of the JCPOA could push China to pressure Iran back to the agreement and divert some diplomatic resources to mediate between Tehran and Washington. Yet, if the state of China-U.S. competition offers little hope for the latter, the chance that Chinese officials privately exposed their concerns to the Iranians should not be ruled out completely. The news of an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) visit to Tehran following the detection of uranium particles enriched at 84 percent and the intensification of diplomatic exchanges between Iran and regional actors (including an imminent visit by the Sultan of Oman, a critical mediator during the JCPOA negotiations) indicate that something around the JCPOA is moving again, although in an unclear direction.

If, as indicated by Fan, Xi’s words reflect China’s renewed desire to advance the negotiations, it might be evidence that Beijing has realized that the Iran deal saga has come to a breaking point, and the current precarious equilibrium might collapse.