The ancient citadel of Luang Prabang, hidden away in the mountains of northern Laos, has miraculously survived for centuries. Preserved by its picturesque isolation, it is the iconic center of Lao Buddhism, culture, and history.

Waves of tourists are expected to flood Luang Prang this year, buoyed by a succession of upbeat reviews from outlets like National Geographic, CNN, and Time magazine, all listing this much-loved UNESCO World Heritage-listed town as a must-see Asian destination in 2023.

But the predicted tourism recovery and economic revival is clouded by more dire news for the town renowned as an unspoiled oasis of eco- and cultural tourism.

Construction has just started on a huge dam just 25 kilometers upstream from the heritage town, and only four kilometers from the revered Buddhist shrines hidden inside the Pak Ou caves.

Even worse news is that the Thai developer is building this dam in an earthquake-prone zone. “We are very worried about the seismic fault only 8.6 kilometers from the Luang Prabang dam site,” said leading Thai seismologist Punya Churasiri. “It is too dangerous to go ahead with this project.”

Satellite information from the Stimson Center’s Mekong Dam Monitor proved that these warnings have been ignored, and serious construction of the Luang Prabang Hydropower Project (LPHP) coffer dam has commenced.

The serenity of the riverside has been shattered by the din, dust, and disruption of dam construction.

Construction on the Luang Prabang dam site. The dam site in 25 kilometers from the heritage township of Luang Prabang, but its impacts will be felt over a much wider distance through its reservoir. Photo © Bangkok Tribune/ S. Chuen.

Will Luang Prabang Become a Paradise Lost?

Laos, in signing the 1995 World Heritage agreement with UNESCO, had pledged to conserve nature, culture, and history along the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Khan rivers.

Yet UNESCO’s appeal to the Lao government to stop the construction has been ignored. Thai investor and engineering corporation CK Power, a subsidiary of Bangkok-based Ch.Karnchang, has surged ahead with construction this year.

In April 2022, a UNESCO detailed monitoring report made it clear that this 1,460-megawatt hydropower project, given its perilous proximity to an active earthquake zone, was a major threat to the integrity and safety of one of Asia’s outstanding world heritage sites.

This report made a comprehensive assessment of the possible heritage impacts. In its conclusion, the monitoring mission recommended that Laos “take the precautionary approach, not to pursue the LPHP, and relocate the project.”

But this 2022 report has been largely ignored. “The Lao government and developers of the Luang Prabang dam have again chosen to ignore the evidence,” commented Gary Lee, Southeast Asia program director at International Rivers. “It shows that profits and vested interests are driving decisions, not science or concern over the multiple economic, environmental and cultural values and benefits the river provides.”

It seems incredible that a host government would risk its UNESCO World Heritage status to build a dam that will bring almost no benefits to the Lao people, according to the Stimson Center’s Brian Eyler, director of the Washington-based think tank’s Mekong program.

“The ostensible reason to build these dams is to support Laos’s economic development, but Laos has given up on ‘battery of the region’ trope,” he said. “Now these dams only drive the country further into debt. Corruption is the major driver of this dam’s development.”

UNESCO awarded Luang Prabang World Heritage status for the harmony between nature and the many cultural and historical treasures at the site. Thai teacher Niwat Roykaew, the winner of the 2022 Goldman Environmental Prize, understands deeply what it means for the citizens of the Mekong to be on the brink of losing Luang Prabang.

“I have seen Luang Prabang. I have seen a beautiful heavenly city. When I visited this heritage city, I saw everything about nature and culture was so good. It had rice, fish, food, greenery, and cultural life in abundance. It was a paradise,” Niwat said.

“If the Luang Prabang dam is built, they will destroy the [ecological] wealth and the abundance of the Mekong River. We will lose the Heavenly City. It will be a paradise lost. And to build a dam is very terrible for the ecology of the Mekong River.”

Choking the Free Flow of the Mekong

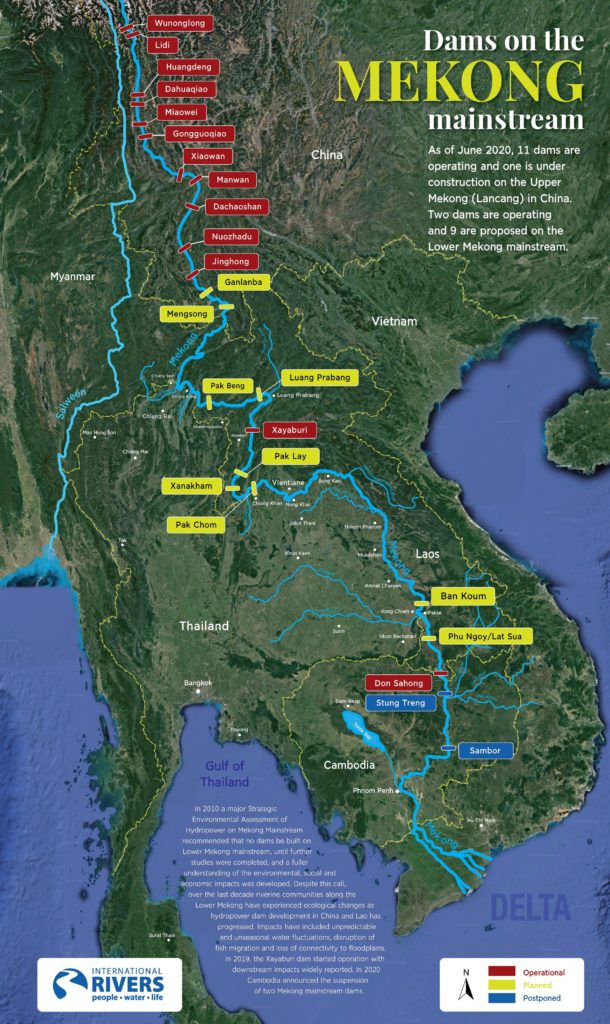

Luang Prabang is becoming encircled by a nexus of dams and reservoirs, according to Dr Philip Hirsch, emeritus professor of geography at Sydney University. “The riverside of Luang Prabang has already been turned into a quasi-lake from the back-up impacts of the Xayaburi dam, 130 kilometers downstream,” Hirsch explained. “The tail end of the Xayaburi reservoir stretches 20 kilometers upstream from the UNESCO site.”

If the LPHP project moves forward, from Xayaburi to Luang Prabang to Pak Beng to the Lao-Thai border – a distance of over 700 kilometers – the Mekong will morph into a network of still-water reservoirs. This means the free flow and quintessential life of the river, vital to the survival of fisheries and food security of tens of millions of people, will be gradually choked until the river will cease to function as one.

This fragmentation of the river alarms many in the tourist industry, especially tour agencies that send traditional Lao boats on a two-day ecotourist trip along the Mekong from the Thai border to Luang Prabang. Long before the Pak Beng dam is completed, their business will be ruined.

“The dam will discourage tourists and will block boat travel all along the river from the Thai border,” a Luang Prabang guide told The Diplomat. “It will make problems for our way of life.” Like most locals I spoke with, the guide did not want to be quoted by name, fearing reprisal for criticizing Laos’ government.

Traditional Lao river boats are important for the local economy and a key part of the ecotourism routes from Thailand to Luang Prabang. Photo by Tom Fawthrop.

Has the Mekong River Commission Failed?

Most regional policymakers look to the Mekong River Commission (MRC) a body composed of Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam, to facilitate environment protection. But as a consultative body, it lacks any veto powers over the decisions of member-states.

In its regional stake-holder consultation in 2020, the MRC classified the Luang Prabang dam “as an extreme-risk dam,” but stopped short of recommending an end to the project, or an in-depth study.

The MRC strangely failed to consult with any World Heritage experts, and apparently did not hire any seismologists to assess dam safety. As Punya Churasiri, the Thai seismologist, observed, “A cascade of dams that can trigger reservoir-induced seismicity has not been investigated by the MRC.”

Hirsch has criticized the MRC’s scope for being too narrow. “While [MRC’s] prior consultation cannot veto a dam, they have neglected to provide a full study of heritage impacts,” he said.

According to Lee of International Rivers, “the construction of Luang Prabang dam also points to the failure of MRC and its Prior Consultation process. The Joint Action Plans (JAPs) have done little to meaningfully address concerns raised by communities, civil society and neighboring countries.”

If UNESCO ever had any hope of curing Laos’ communist leaders of their “dam-fever” – with 65 Lao hydropower dams in operation in 2019, the government is milking each and every river for electricity – that appears to have been wishful thinking.

But there was a more realistic prospect of exercising influence on the Thai government through lobbying by Thailand’s northeastern network of river NGOs. Bangkok has long supported electricity imports from Lao hydropower. If Thailand had listened to the voices of civil society and Mekong experts, alternative options were possible.

There were several sound reasons for Thailand to change its energy policy and not buy into this high-risk project. Lee pointed out that Thailand “has a massive oversupply of electricity – its reserve margin is equivalent to more than 10 Luang Prabang dams. Thailand has a reserve margin of 16,900MW or 34 percent, which is more than double the international norm for reserve margin of 15 percent.”

Lee concluded, “This highlights that the key driver of dams is not energy demand and security, but rather generating profits for a few at the expense of the Mekong and the communities that depend on the river.”

However, the government’s Thai Energy Council ignored the contradictions and the same old policy was renewed. Last year, Thailand signed an MOU for three new dams on the mainstream Mekong, including the Luang Prabang Hydropower Project, complete with power purchasing agreements. That places Bangkok at odds with its UNESCO obligations to protect world heritage.

The Mekong River Commission Secretariat in Vientiane, Laos. Photo by Tom Fawthrop.

Heritage vs. Hydropower

The MOU that commits Thailand to buy electricity from the LPHP is clearly in conflict with Thailand’s U.N. obligations. According to section 6.3 of the U.N. 1972 World Heritage Convention, of which Thailand is a signatory, “Each state party undertakes not to take any deliberate measures, which might damage directly or indirectly the cultural and natural heritage situated on the territory of other state party to this convention.”

Minja Yang, a former UNESCO heritage chief for the Asia-Pacific, clarified: “The government of Thailand, as a State Party to the World Heritage Convention has an obligation to stop companies registered in their country from harming World Heritage sites not only within its territory, but also in other countries.”

However the case of Luang Prabang sadly illustrates how the 21-state intergovernmental World Heritage Committee is longer capable of preventing harmful public and private works. The Luang Prabang dam is just the latest in a long line of destructive dams that jeopardize the world’s heritage.

UNESCO’s sanctions against member states that fail to protect their heritage sites are limited to being placed on the “Heritage in Danger” blacklist.

But as the damage to the natural heritage of the Mekong River is irreversible, being added to the blacklist will have no effect unless UNESCO can close down the dam. And that is highly improbable.

Even a dam-blighted and endangered Luang Prabang would still attract some tourists, especially on the new Chinese-built international express train from from Yunnan province to Vientiane. But it will no longer be the same ecological paradise that it has been for most of its history.

Minja Yang, who just retired last year as President of Leuven University’s International Centre for Conservation in Belgium, lamented, “If we lose Luang Prabang, a very unique site that will be lost to humanity. Once the damage is done, it will be irreversible. It cannot be undone.”