Last week Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka signaled that his government is reconsidering a police cooperation agreement with China, with an eye to terminating it. The memorandum of understanding that was signed in 2011 would enable Fijian police officers to be trained in China, and for Chinese police officers to be deployed in Fiji. This possible change of heart comes after last year Pacific Island states declined to participate in a sweeping region-wide security and trade agreement with Beijing which was seen to be pursued by China with a heavy-hand.

In Suva, Fiji’s “Look North” policy, established under former Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, now looks to be waning. Rabuka has indicated that he sees values and compatible systems of governance as important to Fiji’s foreign policy, and that he is more comfortable with Fiji’s traditional security partners in Australia and New Zealand. This week, Fiji signed a new defense agreement with New Zealand, strengthening cooperation between the two country’s militaries.

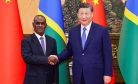

Although China has made gains in the region by convincing Kiribati and the Solomon Islands to shift diplomatic recognition away from Taiwan, and Pacific Island nations will still consider China to be an important economic and development partner, there are strong competing worldviews between these countries and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that would make broader and more intimate cooperation difficult.

Pacific Island countries highly value their sovereignty and are deeply committed to an international system that protects state sovereignty, regardless of the size of each state. A world without such rules and restraints on the actions of larger and more powerful states is one where these small nations would have limited ability to protect not only their independence, but also their cultures and ways of life. The value of these cultures is often something more powerful states either overlook at best, or actively seek to trample at worst.

While such rules and restraints are fundamental necessities for Pacific Island countries, they go against the nature of authoritarian psychology, which cannot recognize the agency of others, and struggles to comprehend ideas like reciprocity and persuasion. As an ethnic nationalist party, with Confucian cultural values, an unassailable leader, and an entitled pride in its status as a superpower, the CCP has a hierarchical worldview at its core. It is unavoidable that it would see Pacific Islanders as subordinates, rather than partners.

This is an understanding of China illustrated by former president of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), David Panuelo, who wrote a letter earlier this year – while still president – to his fellow leaders in FSM which detailed what he described as “political warfare” conducted by the Chinese government. Panuelo saw that the behavior of the CCP – bullying and disrespect, himself constantly harassed by the Chinese ambassador (to the point of having to change his phone number) and being followed by operatives while in Fiji, Chinese encroaching in FSM’s territorial waters and threatening FSM’s patrol boats, and bribing of local politicians – is in the party’s nature. The CCP is a party that doesn’t understand this to be poor behavior, or doesn’t care.

Panuelo felt that China’s behavior in his country was so excessive that he needed to be blunt and public in his assessments. However, this is unlikely to be replicated by other Pacific leaders. Instead there will most likely be a polite, delicate, and quiet distancing from China as a partner of choice, particularly on security issues. But also potentially a more cautious approach to China on other issues of strategic importance.

As the leader of one of the more influential Pacific Island countries, Rabuka may now be looking to set the regional tone and send subtle but clear signals. It is reasonable to assume it is not a coincidence that his government announced its reconsideration of the security agreement with China just before signing a new defense agreement with New Zealand. The timing signals the intent, without having to make any grand announcements.

Pacific Island countries maintain being friendly to all as a central tenet of their foreign policies, something that is very unlikely to change. Yet such an approach is reliant on the principle of mutual respect. Without it some relationships will be friendlier than others. This is not just an issue with China; the current Australian government has learnt the lessons of its predecessor’s failure to embrace this principle. But while learning from mistakes and readjusting behavior is something of which Australia is capable, it is far less likely from Beijing.