In the late 2000s, when I was a teenager, many popular books were not available in my native tongue – Uzbek. New translations were often poor and good translations were from the Soviet era. That is how I ended up forcing myself to learn Russian one page at a time, and later I switched to English. Many of my friends also grew up reading in Russian and English.

To better understand today’s book market and reading culture in Uzbekistan, I talked to local publishers, editors, translators, and book bloggers.

You cannot find Uzbekistan on any list of nations that read the most. A few observations suggest that we do not read enough. Books still remain relatively expensive compared to the average income and there are not many professional printing and publishing houses in the country. Besides, the country’s transition from using the Cyrillic alphabet to a Latin-based alphabet is still not completed, creating additional problems with publishing.

In just 20 years, the number of public libraries and information resource centers shrank from 6,027 in 2000 to 400 in 2021. In rural areas it is even worse – of 5,014 libraries in villages in 2000 only 39 are left. Those libraries are home to just 44 million books. For 2022, the annual circulation of books and journals in Uzbekistan was 5.2 million – a miserable number for a population of 35 million.

Is demand for books low because there are not many well-written and well-translated books, or is the quality of books in the local market low because there is no demand?

“In recent years, demand and attitude towards books in Uzbekistan has changed in a positive direction. I believe this is because of more promotion of books and reading than ever before,” said Maghfiratbegim Azizova, translator and editor from Samarkand in an interview with The Diplomat.

The government change in 2016 had a positive impact on this as well. Firuz Allayev, founder of Asaxiy Books, a Tashkent-based publishing house and book store chain said that “the system in Uzbekistan has been cleaned up a little. Educated (well-read) people are now living better (and) there is a demand for knowledge.” He added, “Where there is freedom of speech, there is always an interest in books. People want to understand what is happening around them.”

Sanjar Nazar, founder and director of the Akademnashr publishing house, which publishes around a million books a year, also noted that reforms under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s regime initially “liberated” the publishing sector. “The first years of the ‘New Uzbekistan’ era were good for books because of a number of concessions given to bookstores” and the publishing industry, he said. “For example, publishers now do not need a special license. Registration with a regulatory body is enough. There is also no need to get the content of the book approved by any state representative body, except for religious literature.”

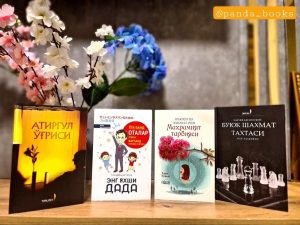

Book bloggers and reader communities emerged over the last few years and started writing book reviews, which inspired people to read more. “People, especially the younger generation, face difficulty choosing books and need advice about good books. There was not much information about publishers and bookstores, so I decided to take first steps in this field and create quality and useful content in Uzbek,” said Jasurbek Bozorboev, who runs the PandaBooks blog.

Allayev says he founded Asaxiy Books after observing social media discussions. “Following the government change in 2016 and given relative freedom, in many social media discussions people started talking about the necessity of reading this and that book, but those books were not available in Uzbek. Seeing this, we first wanted to translate three books and distribute them as donations. But after observing and studying the market, we learnt that nothing will change much with three books. So, we had an idea of starting a big project that will develop the book market. The goal was to directly change the reading [culture] and book market in Uzbekistan.”

The book market in Uzbekistan has its own peculiarities. A majority of books are still published in the Cyrillic alphabet, which was introduced by the Soviet regime in 1940. Tashkent pledged to switch to a Latin script in 1993 and the last phase was supposed to be completed by 2023 after several delays.

“The alphabet has remained a political issue,” added Nazar. “Here, the Latin script is one of the conditions of independence… . There is a view that with Cyrillic we will remain within the cultural and informational space of Big Brother [Russia] and thus it should be avoided.”

A majority of the younger generation, however, prefer reading in Latin since public schools teach the Latin script. But because the Russian language is still part of the mandatory education, everyone also learns the Cyrillic alphabet at schools too.

“The reason why we print most of the books at Asaxiy in the Cyrillic alphabet is that our audience is mostly middle-aged, and mostly young people who have graduated from school, and they read more in the Cyrillic script – mainly because the press is also in Cyrillic script,” said Allayev.

“I believe that the main reason for [the Cyrillic alphabet still being in use] is that older readers cannot read in Latin,” said Bozorboev. “Today the main reading group is the generation that reads in Latin. That’s why I and almost 99 percent of book bloggers write in Latin. In recent years, most of the big publishers have gone through Latinization, which is certainly a good thing. Cyrillic is not a problem for me, but I am in favor of writing and reading in Latin.”

Not only is the Cyrillic alphabet still in use, but books in Russian are also marketable. The Tashkent branch of Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russian Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation claims that one-third of the population in Uzbekistan speaks Russian, but this is an overestimation. “We have a certain Russian-speaking class who believe that the war [in Ukraine] and the current Kremlin policy have nothing to do with the Russian language, and they are right,” said Azizova, commenting on sales of books in Russian. “Another group of readers still has a high level of sympathy for the Russian language and even for Russia.”

“After the start of the war between Russia and Ukraine, the demand for books in the Russian language seemed to increase a little, mainly because many labor migrants and refugees from Russia came to Uzbekistan and settled here,” Allayev said, reflecting on sales of books in Russian. But as Russian migrants left, demand for books in Russian went back to the previous level.

“One of the happy sides is that unlike in other Asian post-Soviet countries, there are not many books in Russian in Uzbekistan. The best quality books are in Russian (of course), but their share in the total market is less than 15 percent,” noted Nazar. However, this might change in the coming years. Elites and the middle class send their kids to Russian schools or they participate in Russian groups at Uzbek schools. Those kids are growing up reading in Russian.

World literature is translated mostly from Turkish and English. Turkish religious literature is very sought-after in Uzbekistan. In general, religious books are more expensive than books of other types. “If we take it in terms of consumerism, first of all, there is a strong interest in Islamic-religious and educational books. It should be noted that such books are very popular among young women and girls. Young men prefer detective and adventure works,” Bozorboev clarified.

Other types of books are mostly translated from English, but the quality is not always good. “To be honest, I am not satisfied with the quality of the books that are published in Uzbek. Due to a low demand for books in our country, the cost of labor in book-translation is a very painful point,” explained Azizova, who works with book translations. “There are few publishers and projects that can pay enough to experienced professionals for translations. In addition, many talented people are forced to search for a job in other fields because translation and editing are paid much less. As a result, book translation and editing are mostly left in the hands of mediocre professionals.”

Not all local publishing houses follow copyright regulations either. This is partly because having a contract with an author or agency takes time. For publishing houses in Uzbekistan, getting copyright for translation and publishing world books is also very expensive. As a result, the market is filled with “pirated” books.

Article 1056 of the Civil Code requires a contract-based “copyright license agreement” between a publishing house and an author or owner of a book for books to be translated and published in Uzbekistan. Contracts are registered at the intellectual property agency. Liability for translating and publishing works without author’s permission, however, arises only when author sues the violating publishing house, explained O’ktamjon To’khtayev, a lawyer who focuses on copyright issues in Uzbekistan. Foreign copyright holders may not know their books have been illegally translated and published in Uzbekistan.

The regime change in 2016 and relative freedom of speech positively impacted reading culture in Uzbekistan. People, especially the younger generation, have started reading more and more bloggers have started promoting reading. The overall situation, however, still remains poor.

The author thanks Nodirbek Madrahimov for all the contacts he made possible for this article.