In the last few years, China’s government has promoted increasingly conservative social values, encouraging women to focus on raising children. It has cracked down on civil society movements and made laws to drive out foreign influence.

So a 75-year-old Japanese feminist scholar who’s not married and does not have children is an unlikely celebrity on the country’s tightly censored internet.

But Chizuko Ueno, a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, is a phenomenon. She leapt to fame in China in 2019 with a speech that criticized social expectations for women to act cute and the pressure they face to hide their success.

Ueno’s popularity reflects a surge in interest in women’s rights, said Leta Hong Fincher, a research associate at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute who has written about gender discrimination and feminism in China.

About a decade ago, China had a rambunctious feminist movement that staged protests like occupying a men’s restroom to demand more toilets for women, and marching in wedding dresses spattered with fake blood to draw attention to domestic violence. But that movement has been silenced as President Xi Jinping’s administration tightens controls on civil society and promotes conservative family values in a bid to boost childbirths.

Ueno declined multiple requests to be interviewed for this story.

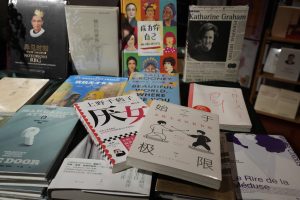

In mainland China, Ueno’s books sold more than half a million copies in the first half of 2023, according to sales tracker Beijing OpenBook, and 26 were available in Chinese bookstores as of September. They cover topics ranging from “misogyny” in Japanese society to feminist approaches to elder care issues in an aging society.

“Starting From the Limit,” a collection of letters between Ueno and Suzumi Suzuki, a writer who used to act in Japanese porn, topped the 2022 Books of the Year list on the popular Chinese review platform Douban.

Fans said Ueno’s openness about choosing not to marry or have children makes her a role model.

Edith Cao, a writer who spoke on the condition of being identified by her English nickname due to fear of government retaliation, said seeing an East Asian woman succeed without a family helped her decide not to marry. Yang Xiao, a graduate student, said Ueno’s example helped assuage her anxieties about being single and inspired her to start booking holidays alone to build confidence.

Relationships are a divisive issue even among Ueno’s Chinese fans. Earlier this year, fans attacked a Chinese video blogger who asked Ueno if she hadn’t married because “she’d been hurt by men,” saying the blogger had reinforced traditional assumptions. That started a series of online conversations about marriage and feminism that lasted for months, with related hashtags drawing some 580 million views on the Twitter-like social media platform Weibo.

Ueno doesn’t write about China, and that’s probably one key reason her books have escaped censorship, said Hong Fincher.

Feminist ideas are not banned in China, but authorities view all activism with suspicion.

Police regularly summon owners of bookstores and cafes and pressure them to cancel feminism-themed events, several organizers and founders told The Associated Press. Online, posts that refer to the #MeToo movement are deleted, and nationalist bloggers attack feminists with a public presence as foreign agents.

Chinese journalist and activist Huang Xueqin, who helped spark China’s first high-profile #MeToo case, was tried last week for allegedly inciting subversion of state power. According to a copy of the indictment published by supporters of Huang, she was accused of publishing “seditious” articles and facilitating training activities on “non-violent movements.”

Protest and campaigning are no longer possible, said Lü Pin, a Chinese feminist activist based in the United States, meaning feminism is confined to individual action and small groups. The Ueno boom, she said, has helped keep feminist ideas in the “lawful” mainstream.

Megan Ji, a 30-year-old financial analyst, said it wasn’t until she read one of Ueno’s books that she began taking an interest in the ideas of feminists.

That helped her confront her boss when he began caressing her back at an after-work karaoke party with colleagues and potential business partners. She works in a competitive industry in which fitting in at after-work parties is widely considered vital to her job, and another woman hadn’t said anything when a drunken manager placed his arm over her shoulder.

But when her boss began badgering her to sing, she shouted: “Do you respect me? Who do you take me for?” Her colleagues were shocked, but Ji’s boss apologized, both on the spot and again the next day. Ji said she didn’t suffer retaliation, and no awkward parties have happened in the office since then.

The AP could not independently verify Ji’s account, and she requested to be identified by her English name to avoid repercussions from her company.

Guo Qingyuan, a 35-year-old copywriter, said that reading Ueno led him to question how he saw women. He stopped talking about women’s looks with his buddies, he said, and sought out children’s books for his daughter that didn’t promote stereotypical gender roles.

Cao, the writer who also offers support to victims of domestic violence, said there are problems that reading feminist books won’t solve.

Two years after China first added “sexual harassment” as a cause of lawsuits in 2019, the Yuanzhong Family and Community Development Service Center, a Beijing-based nonprofit group, found that only 24 cases using the law were recorded in a nationwide database. The researchers identified 12 other cases related to sexual harassment that were filed using other laws.

Ueno-inspired feminism is unlikely to bring direct pressure to change laws. It’s a lot tamer than earlier waves of activism, although it may be more widespread.

But “even if her words can’t bring policy change,” Cao said, they “have further stoked an underlying force.”