The year 1943 saw several turning points in World War II. In February, the Red Army’s victory at Stalingrad marked Hitler’s first major military defeat in the European theater of war and the beginning of the end of Nazi Germany. Days later in the Asia-Pacific theater, American forces won the first land offensive against Imperial Japan at Guadalcanal. The Allied invasion of Sicily that summer led to the ousting of Mussolini and the collapse of his Fascist Italian regime. By the end of that fateful year, dubbed World War II’s “forgotten” year of victory, the Axis powers had lost all prospects of winning the war.

In October 1943, the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Republic of China issued the Moscow Declaration. In this statement, the four major Allied powers pledged jointly to fight the Axis powers until their unconditional surrender and work toward the establishment of a permanent international organization for peace: the United Nations. In the ensuing months, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill successively convened with China’s Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek at Cairo and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at Tehran to discuss strategies for defeating the Axis powers and the foundations of a post-war order.

Memory as Battlefield: Shifting Alliances

Eight decades on, as living memory of World War II is fading, the official memory of that global conflict has become a battlefield of its own, with the four one-time allies today split across two rival camps. On one side, Russia under Vladimir Putin and China under Xi Jinping have been refashioning and repurposing the memory of World War II to shore up their legitimacy at home and remind the West of their rightful place in the global order. On the other side, the United States, Australia, Japan, and European actors have countered Beijing and Moscow’s historical statecraft through controversial remembrances and historical revisionism of their own.

Despite this ongoing contestation of memory and the reshuffling of global positions it reflects, remarkably little is known about Chinese and Russian strategic endeavors aimed at aligning their official remembrance of the momentous conflict that brought about the post-war world order – an order that is now under attack from within. Recent research on China-Russia ties tends to focus on “hard” security and geoeconomic factors, resulting in conflicting assessments of the depth and durability of this bilateral partnership. And while the mutually constitutive links between historical memory and foreign policy have been studied at length in the context of China-Japan relations – think “textbook wars” and “apology diplomacy” – similar research in relation to China and Russia is absent.

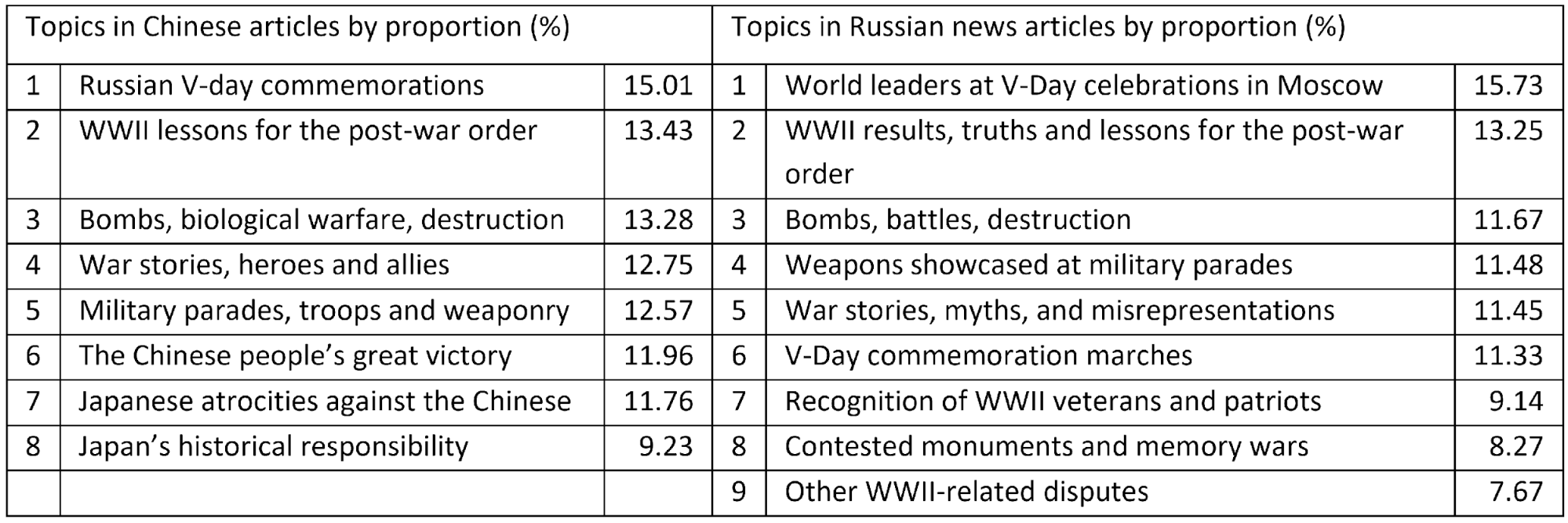

Our own research on narratives of World War II in Chinese and Russian state-controlled news agencies suggests that this domain is in a state of flux, with some apparent convergence. In a recent study, we used structural topic modeling (STM) to analyze a corpus of 5,262 articles published by Chinese and Russian state-controlled media outlets between 2005 and 2022 that reference World War II. Our initial findings reveal a remarkable congruence between the two sets both in terms of topics covered and their relative prevalence (see Figure 1). An analysis of developments over time, both within and across topics, further shows that Chinese and Russian narratives are converging on some key points, most notably on the results and lessons of World War II for today’s global politics.

Figure 1. Prevalence of topics in Chinese and Russian news articles on World War II, 2005–2022.

Chinese Narratives: Referencing Russia

This convergence in topics is in fact almost entirely a product of shifts in the Chinese coverage of World War II. Of the 2,455 English-language articles on World War II published since 2005 by our four selected state-controlled outlets (Xinhua, China Daily, China.org, and Global Times), war remembrance in Russia was the most widely covered of eight topics, with a proportion of 15.01 percent. In addition, about half of all articles belonging to the second-most (World War II results and lessons) and fifth-most (military parades) prevalent topics also contained numerous references to Russia.

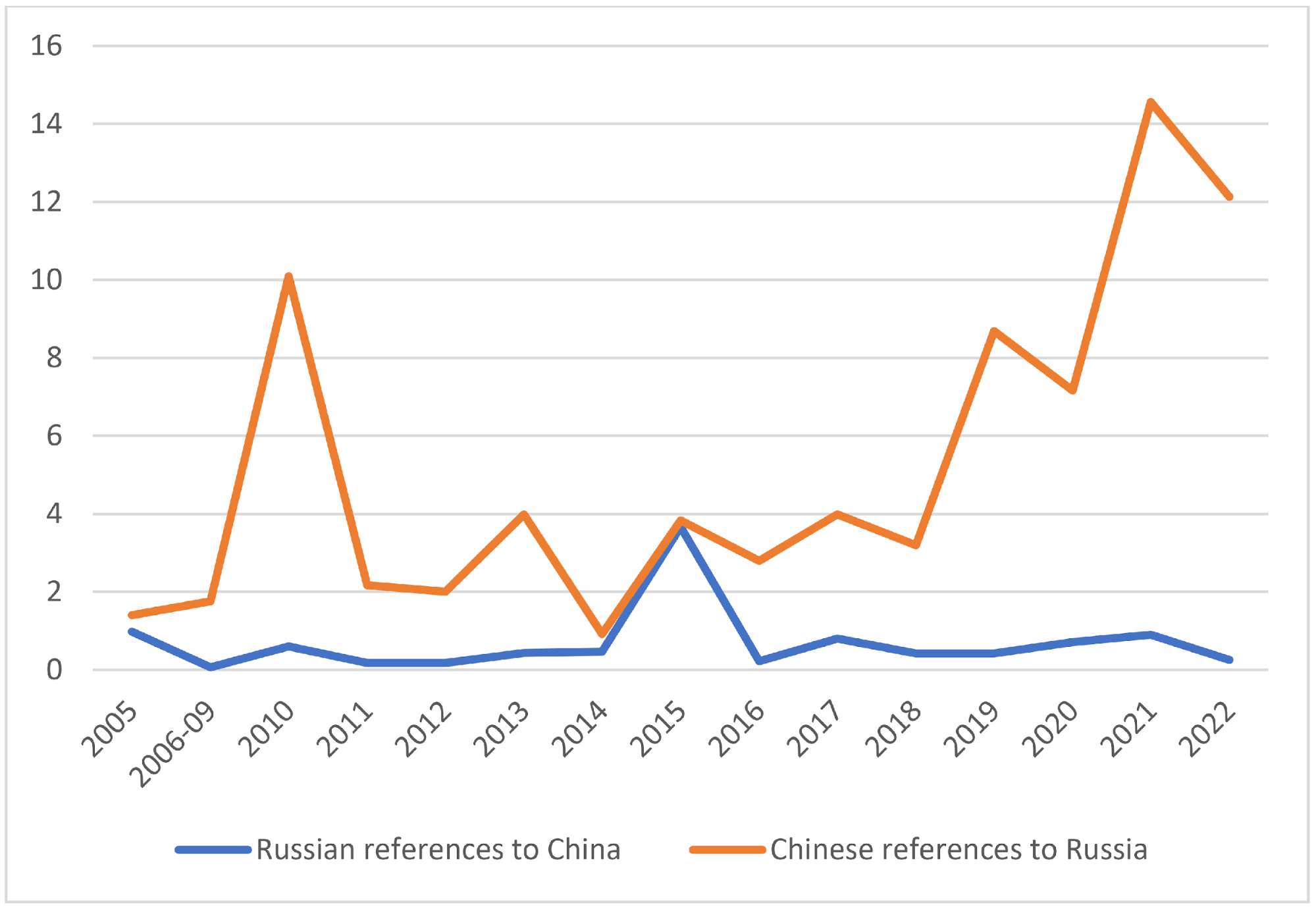

One explanation could be that Chinese articles mention Russia more often during major anniversary years (2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020), which typically see the two countries organize joint commemorations and when their national leaders visit each other. The further spikes in 2019 and 2021 most likely reflect the positive development of Sino-Russian relations prior to the Ukraine war and their converging views on world order.

Figure 2. Frequency (per 1,000 words) of mutual references

Japanese atrocities against the Chinese – often thought to be the epitome of Beijing’s official discourse on World War II – have a topic proportion of only 11.76 percent (ranked seventh), while Japan’s historical responsibility in the region and related disputes is at the bottom of the list with only 9.23 percent. Remarkable as this may seem, it aligns with a previously observed shift in Beijing’s war discourse away from victimhood narratives. As detailed elsewhere, the triumphalist turn under Xi has seen Japan’s image as evil “Other” reduced and subsumed into a broader set of external forces threatening China’s “rejuvenation.” It is now the United States that represents the main threat to peace in Chinese official discourse, and this is precisely where a real convergence in Beijing and Moscow’s narratives can be found.

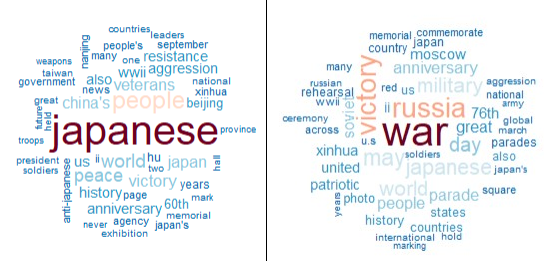

Figure 3. Word clouds for Chinese news articles on World War II in 2005 (left) and 2021 (right). Note the increased prevalence of the words “Russia,” “Russian,” “Soviet,” and “Moscow” (2021) at the expense of “Japan” and “Japanese” (2005).

What is striking is not only that “Russia” has become a highly prevalent topic and keyword in Chinese media discourse on World War II but also that Chinese state media reports have begun to make explicit use of the term “Great Patriotic War” – a term used in the Soviet Union and today in Putin’s Russia – in their narratives. This is particularly significant in view of the fact that importing foreign historiographical concepts is highly uncommon in China, where World War II is officially known as “the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War” and “World War II” is used in English-language publications only as a temporal marker.

Russian Narratives: Still Facing West

While Chinese news agencies increasingly reference Russia in their articles on World War II, there is no such trend in Russian references to China. Our STM analysis of 2,807 articles published between 2005 and 2022 by the Russian news outlets Russia Today (RT), Sputnik, and TASS indicates that China is rarely mentioned in articles on World War II.

The Chinese war theater has never played a particularly prominent role in Soviet and Russian memory, and our research shows that this continues to be the case today, despite Beijing’s increased strategic importance to Moscow. The only aberration is a relative spike in references to China in 2015, when Xi Jinping joined his “best friend” in Moscow to honor the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and Putin reciprocated by attending China’s massive military parade at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

Therefore, although both Chinese and Russian articles highlight the duty to defend the historical truths of World War II, there is an asymmetry in how often they reference each other when recalling the war: The Chinese increasingly talk about Russia but the Russians rarely talk about China. Instead, the Russian articles reveal an almost exclusively westward orientation.

War stories (the fifth-ranked topic) are far more concerned with the wartime spirit of Soviet–U.S. cooperation or the Elbe meetings between Soviet and American troops in April 1945 than with the Sino-Soviet wartime friendship. Some of these articles call for a revival of this spirit of Russo-American solidarity, whereas others warn against attempts by former Soviet states, the EU, and the United States to distort such historical “truths” and key lessons of World War II.

Limited Friendship: Shared Histories, Distinct Memories

A closer inspection of the dataset of Chinese articles reveals that Russia’s preoccupation with the West is not the only barrier to deeper convergence between Chinese and Russian narratives of World War II. Indeed, despite the numerous references to contemporary Russia and lessons from the War in the Chinese articles, there is no deeper convergence of historical narratives.

Of the 313 articles recounting various war stories (the fourth-ranked topic), the thousands of Soviet pilots who aided China during the early stages of the resistance against Japan are mentioned in only a handful, and even these avoid elaboration on this shared past. This is in sharp contrast with the 80 articles that recall the efforts of the U.S. “Flying Tigers” in China. In line with standardized Chinese history textbooks and museum exhibitions, China’s state media reports tend to minimize the Soviet Union’s historical contribution to China’s war effort.

Various factors may account for this selective amnesia. Foremost is the deeply Sinocentric and CCP-centric nature of official Chinese memory, a trait that has become even more marked with Xi’s triumphalist turn. Reflecting the exclusive grip of the Chinese party-state, Chinese media analyses of war history are highly stylized and essentialized, to the point of abstraction.

Moreover, the fraught nature and sensitive history of China-Russia relations continue to constrain their professed no-limits friendship. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Beijing appears to have diversified its memory strategy by shifting focus away from historical conflicts to contemporary peace-building efforts and the present-day heroes and martyrs of “peace-time China.”

A major paradox of authoritarian memory governance is that although history in such governance systems can reflect only a single, correct “truth,” the core lessons of official memory are at the same time deeply volatile and subject to constant revision according to strategic goals. If Moscow inspired Beijing between 2005 and 2021 to rediscover and refashion the memory of World War II as a mobilizing and unifying force, recent Russian actions appear to have elicited the opposite response.

A more fine-grained analysis of the dataset is needed to confirm this impression and yield deeper insights. But what is already clear is that while Chinese and Russian media outlets are increasingly engaging with similar topics, in line with Beijing and Moscow’s endeavors to align and mobilize World War II memory for strategic purposes, there has been no substantive convergence in their historical narratives.