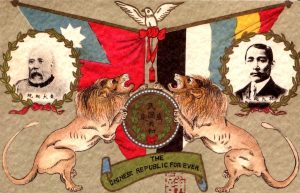

China’s last dynasty fell in 1912, and the Republic of China was born. The next 37 years – a period of internal conflict and foreign invasion – are often viewed as a historical interregnum, the lead-up to the Communist forces’ victory and the founding of the People’s Republic of China (ROC) in 1949.

Yet the early period of the ROC is worth a closer look. It set the stage for the emergence of a modern Chinese state, and was a period of intense cultural activity as well.

Xavier Paules explores this often overlooked period of Chinese history in his new book, “The Republic of China: 1912 to 1949” (Polity, 2024). Paules, an associate professor in history at EHESS, Paris, argues that the ROC period deserves attention in its own right, both for its “intellectual brilliance and vitality” and for an understanding of how, precisely, the ROC fell – an event that, despite the CCP’s proclamation of historical destiny, was not preordained.

Your book covers the Republic of China from 1912-1949, but during that time, control of the government shifted hands repeatedly, through political machinations and outright coups. To set the stage, can you give a brief overview of who was actually in control of the ROC at various points in its early history?

I am glad you insist on the early history of the Republic of China because this period is often overshadowed in the historiography by the Nanking decade (1928-1937) and the Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945).

After the collapse of central power consecutive to the death of Yuan Shikai (1916), the situation no doubt became a confused one. In the north of China, three powerful cliques (Zhili, Fengtian, and Anhui) were in competition. These cliques were coalitions of military men organized around a leading figure.

These three cliques were competing at two levels: first, for the control of the Beijing Parliament and central government (the de jure government of China). Second, the cliques struggled to strengthen their military might and expend the territories under their domination.

The chronology of 1916-1928 was characterized by a whirlpool of negotiations, compromises, shifts of alliances, betrayals, military skirmishes, and some outright wars (like the 1924 Second Zhili/Fengtian war). These cliques were able to form blocs of provinces, some amounting at their peak to as many as a dozen. The political endpoint of their rivalries was the country’s unification: the clique that would prevail over its opponents would virtually lead the country.

The south of China was not directly involved in the major clashes between the Anhui, Zhili, and Fengtian cliques. Local power holders had asserted themselves there too, but they were of a smaller caliber. They were struggling only to consolidate and extend their satrapies. Conflicts were just as fierce as in the north, the main difference being that the opponents could harbor no dreams of reunifying the country.

Various foreign powers, including Japan and the Soviet Union, took a direct hand in backing different players within China during this period (for example, the Soviets provided funding and training to both the KMT and the CCP). How important were these foreign interventions in shaping the trajectory of Chinese politics during this time?

You are perfectly right to mention that the Soviets helped not only the CCP but also the KMT. But if it is well known that between 1923-27 Moscow helped the KMT to strengthen its Guangdong base as well as to launch the Northern Expedition (1926-1928), it should be underlined that the USSR again provided vital military help to the KMT during the first years of the Sino-Japanese war.

Stalin was eager to check the Japanese threat on Siberia. Between 1937 and 1941 as many as 5,000 Russian instructors, advisers, and technicians served in China. As a consequence, it is arguable that the USSR, among all the foreign powers, had the strongest impact on shaping the trajectory of Chinese politics: Of course, by supporting the final victor, the CCP, but also by enabling the KMT to prevail over warlord forces in the Northern Expedition and reunify the country, then by enabling it to resist the Japanese invasion.

Other powers were influential actors in China during the Republican period. The U.S. was backing the KMT after 1941 and during the Civil War period. Japan was not only the aggressor in 1937 and the creator of the puppet state of Manchukuo; its influence was strongly felt in the north of the country during the 1910s and 1920s.

However, in my book I re-evaluate also the importance of other foreign powers. For example, Germany’s influence was strong also during the Nanking decade with German military advisers and instructors working hard to train and reorganize the military forces of the central government. As to France, by proxy of Indochina, it was a key protagonist in Yunnan during most of the period.

How did the ROC government(s) interact with or respond to the immense cultural changes, typified by the “May Fourth Movement,” during this period?

In terms of intellectual brilliance and vitality, the Republican period has often been compared to another period Chinese history, called the Warring States era (481-221 BCE). These two periods shared one characteristic: the absence of a strong central power.

Clearly, the weakness of the central power during the Republican period was a blessing for the intellectual life, and allowed cultural trends like the May Fourth Movement to blossom. The typical example is Peking University: Under the intellectual leadership of Cai Yuanpei, the 1917-1926 decade was incredibly fertile for the university and the May Fourth Movement came out of these heydays of freedom of thought.

The situation worsened as the KMT reinforced its grip over the academic world and the press during the Nanking decade. But there is no comparison with the lock-out imposed on China intellectual life by the CCP after 1949. The Republic, as a whole, can be characterized as a time of intellectual freedom. In the 1930s the KMT had somewhat dimmed the light, but after 1949 the CCP simply shut the power off!

The main thesis of your book is that the fall of the ROC – and the rise of the CCP – was not inevitable. What would you say were the three factors or events that were most important in shaping this history – without which, the ROC might still be ruling China today?

Thank you for underlining that point, which is indeed crucial.

Undoubtedly, the factor number one was the 1937-1945 Sino-Japanese war. During the Nanking decade, the Kuomintang struggled hard to reinforce central power and eliminate its opponents (the remaining local warlords and the CCP). And it did very well.

As for the CCP, it was on the verge of complete annihilation in 1937; only the outbreak of war saved Mao Zedong. In 1972, in his typically provocative fashion, Mao told Tanaka Kakuei, the acting Japanese prime minister, that the CCP should be grateful to Japan for its aggression, because without that they would never have come to power. This statement reflects the fact that the 1937-1945 war radically altered the balance of power between the KMT and the CCP.

I go even further as I explain (in Chapter 4) that Japan was, from the CCP’s point of view, the ideal enemy. It was strong enough to inflict a litany of defeats on the KMT and to dramatically weaken it in a war of attrition. But on the other hand, Japan was not strong enough to win a total victory or to hold on to the vast territories it conquered, where the CCP put its guerrilla know-how to good use and developed a string of bases.

This is not to say that the game was over in 1945: The CCP still had a long way to go. Then we can mention the second factor, which is no other that Chiang Kai-shek himself. Assessment of Chiang’s achievements as the country leader during the Nanking decade and the war can be considered nuanced. By contrast, during the period of the civil war (1945-1949) the picture is unequivocally bleak. Chiang conducted military operations in a disastrous way, and fall short of curbing the inflationary spiral that was wrecking the urban middle class, the very basis of KMT political support. Chiang was simply unable to understand that this was a key issue, as Parks Coble shows more in detail in his recent book, “The Collapse of Nationalist China: How Chiang Kai-shek Lost China’s Civil War” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

The third factor is connected to KMT leadership more widely. I wish to insist on that, because in my view it has been remarkably downplayed by historians: The KMT’s sclerosis was manifested above all in the absence of renewal within its leadership. From 1945 to 1949, it is clear that the people at the head of the hierarchy were the same as they had been for two decades. Young, efficient, and energetic men had been at the helm during the Northern Expedition (1926-1928) and the Nanking decade (1928-1937); twenty years later, the same men seemed worn down by an over extended political career.

The KMT’s middle-level cadres faced the impossibility of gaining access to the highest-level posts. There was no fresh blood, for example, among the seven successive heads of the Executive Yuan between 1945 and 1949 (whose function was equivalent to the prime minister). The KMT had become gerontocratic.