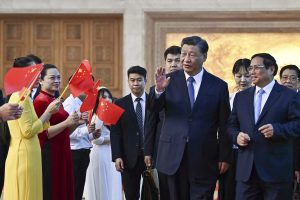

By now, it has been widely accepted that Vietnam has mastered the art of not choosing its foreign relations. Geopolitically speaking, Vietnam has refused to side with either China or the United States in their growing great-power competition. It is also the only country that hosted visits from both Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Joe Biden in 2023. Debates about the future of Vietnam’s foreign policy often revolve around the question of how long Vietnam can sustain its non-aligned foreign policy as Chinese assertiveness at sea grows and the U.S. courtship intensifies. Vietnam watchers often surmise that one day, when the leeway for small states shrink, Hanoi will have to choose between China and the United States.

But to say that Vietnam has rarely chosen, or its options are just either the United States or China is an oversimplification of its external environment and its own agency. Instead of not choosing, Vietnam has long chosen what matters most to its survival: a grand strategy based on a prudent understanding of the intersection between geography and agency. As a small country next to a superpower, Vietnam has limited agency when it comes to deciding its own fate.

Geography adds another layer of complexity to the understanding of Vietnam’s agency. Hanoi is free to choose to the extent that it can protect itself from the repercussions of such an option, with geography providing a natural defense. In other words, Vietnam only chooses options that it is certain will strengthen the advantages already provided by geography. When the “tyranny of geography” is against it, Hanoi will be reluctant to exercise its agency. If it chooses to do so, the costs will be prohibitively high, rendering the move counter-productive to the goal of survival.

A quick review of Vietnam’s strategic choices since 1945 suggests that Vietnam has always chosen a continental orientation and has picked and chosen allies based on its continental security needs. Starting with the First Indochina War (1946-1954), the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), or Vietminh, was confident enough to choose to fight France and to reject independence within a French Union thanks to its geographic proximity to China.

Of course, the Vietminh’s decision to fight the French in December 1946 after trying to buy time to grow its armed forces under the March 1946 Preliminary Agreement between Vietnam and France brought about great destruction to its capital Hanoi, and the retreat of the DRV government to the northern provinces after French forces captured the city. Fortunately for the Vietminh, being close to China meant it could receive reliable and steady material and political support from the Chinese communists against the French army and the French-backed State of Vietnam. The Vietminh’s geographical advantage was so decisive that the French had to rely on airlifts to defend its garrison at Dien Bien Phu, which culminated in the Vietminh’s victory in May 1954 and the successful recapture of Hanoi in October of the same year. The DRV chose the option that was most geographically advantageous to its agency even if that option entailed costly combat against a superior enemy.

When the Second Indochina War (1955-1975) broke out, the DRV once again decided to militarily fight the Republic of Vietnam, and later, the United States. Initially, Hanoi decided to co-exist with Saigon and hoped that the country would be peacefully reunified under a national referendum promised in the 1954 Geneva Agreements. However, after such a prospect faded due to Saigon’s refusal to participate in the referendum, Hanoi chose to resort to the use of force to save the southern communists from Saigon’s persecution.

Once again, its option was informed by a geographical advantage that helped it address the most significant land threat – a strong communist China willing to oppose the U.S. presence in its southern periphery. Chinese participation in the Vietnam War on the DRV’s side, and later Soviet material support, meant the DRV could meet the superior U.S. armed forces head on and reunify the country on its own terms. The United States, wary of a repeat of the Korean War, decided to heed Chinese deterrence signals and did not launch a ground invasion of North Vietnam to avoid direct combats with Chinese troops. As during the First Indochina War, the DRV picked the option that its agency benefited the most from geography, even if the option entailed fighting a militarily superior enemy.

During the Third Indochina War (1978-1991), Vietnam had to choose either accommodating the interests of the Chinese and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia or addressing the Khmer Rouge threat through force of arms and upsetting China in the process. After exhausting all diplomatic options to pacify the Vietnam-Cambodia border, Vietnam opted to launch an invasion to topple the Khmer Rouge in late 1978, prompting a Chinese invasion of northern Vietnam in February and March 1979.

Vietnam’s confidence in exercising its agency against superior China was based on an alliance with the Soviet Union, which was also a land power with the capability to exert great military pressure on China along the Sino-Soviet border to deter a Chinese invasion of Vietnam. Indeed, before China invaded Vietnam, it had to communicate to the Soviet Union that the invasion would be short and limited to avoid a Soviet intervention. Throughout the 1980s, Vietnam did not give in to China’s “bleeding Vietnam white” strategy as it continued receiving massive economic and military aid from the Soviet Union and the Soviets continued stationing a large number of troops along the Sino-Soviet border. Had it not been for the Soviet Union being a mighty land power next to China, hence geographically advantageous to Vietnam’s choice to oppose the land threat posed by the China-Khmer Rouge alliance, Hanoi would not have been able to exercise even this relatively small degree of agency against Beijing.

The bottom line is that, contrary to the idea that Vietnam is “not choosing” in its foreign relations, the country has always chosen the option that it deems most advantageous in terms of its geography. Without these geographical advantages, the Vietminh, the DRV, and unified Vietnam would not have chosen to fight much stronger enemies. It also explains why Hanoi has historically rarely adopted a maritime orientation, and why it has generally lacked the capability to project force into the seas. And with the offense-defense balance favoring offense in the open sea, Vietnam enjoys few geographical advantages in this domain. And technological backwardness and resource constraints mean that it cannot compete against China over the quantity and the quality of naval weapon systems in order to compensate for these geographic disadvantages. Geography is now a barrier to Vietnam’s defending and asserting its maritime claims in the South China Sea, or exercising its agency in the maritime domain.

Another important point is that Vietnam’s continental orientation informs its choice of ally. In all three Indochina Wars, Vietnam allied with the powers that could best support its continental security objectives.

In the modern era, the reason Vietnam has stuck firmly to its “Four Nos” foreign policy, which can be interpreted as a self-imposed limitation on its own agency, is because of geography. The first and second nos – no military alliances and no siding with one country against another – exist because the U.S., a predominantly maritime Pacific power, cannot support Vietnam’s continental security objectives. The third no – no foreign military bases and no using Vietnamese territory to oppose other countries – exists because Vietnam cannot let extra-regional powers violate China’s continental sphere of influence and incur Chinese wrath.

And the last no – no using force or threatening to use force in international relations – exists because Vietnam does not want China to adopt a “bleeding Vietnam white” strategy. Different from the First and Second Indochina Wars, when geography provided decisive advantages to the DRV’s fights against France and the United States, Vietnam’s unchanged geography of being close to China now restricts its agency. Vietnam cannot exercise its agency to choose the U.S. because geography remains a constraint. If Vietnam chooses to exercise its agency with the “tyranny of geography” working against it, Chinese punishments will surely be severe enough to make Vietnam rethink its choice.

Consequently, the contemporary debate about Vietnam’s choice between China and the U.S. is a misguided one because it mistakes the outcome for the cause of Vietnam’s foreign policy. The real options or debate about Vietnam’s foreign policy hence are not between China and the U.S. but between adopting a continental or a maritime orientation. Picking a maritime orientation would mean choosing the U.S. because the United States is a maritime superpower. Choosing a continental orientation means Vietnam will choose not to upset China because Beijing is a continental superpower. And on this score, Vietnam has clearly chosen the latter as it has let the continental security policy dictate the maritime security policy. History has shown that Vietnam has never shied from making difficult decisions, but only when geography has been on its side. It is knowing when to choose and whom to choose, rather than refusing to choose at all, that lies at the heart of Vietnam’s foreign policy strategy.