On February 24, Venezuelan K-8W light attack jets flew from the eastern port city of Guiria over the Atlantic in a show of force directed at the country’s neighbor, Guyana. The Chinese-made aircraft were emblazoned with the slogan “El Essequibo es Nuestro” (“Essequibo is ours”) in reference to the disputed territory claimed by Venezuela but administered by Guyana. The government of Nicolás Maduro has been steadily ratcheting up tensions around the territorial dispute for the past nine months.

In December 2023, Venezuela organized a referendum on whether it should annex the territory. Despite reports of lukewarm enthusiasm and low turnout, Maduro has claimed a mandate to seize Essequibo and Venezuela’s provocations have only grown, reaching what some analysts fear may be a point of no return for the authoritarian Maduro regime. Indeed, Caracas’ threats have proven so troubling that one of the first operations of the USS George Washington’s ongoing tour of South America was a flyover of Georgetown, Guyana, by two F/A-18 Super Hornets to show solidarity with Guyana. The United States and Guyana both insist that the territorial dispute must be resolved through international legal channels, not force or intimidation.

The skies near Essequibo are also indicative of where two great powers have chosen to position themselves on this debate. On the one hand, Venezuela’s K-8Ws are the product of years of tightening economic and security cooperation with China. Indeed, while lacking in comparison to the more sophisticated fighter and attack aircraft in Venezuela’s arsenal, the K-8Ws are the country’s most recent jet acquisitions. On the other hand, the F/A-18 flyover placed the United States squarely in the camp of support for the rule of law, and efforts to deter aggression by Venezuela toward its neighbor.

Guyana and Venezuela showcase the two sides of China’s engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean.

In Venezuela, Beijing has played an invaluable role in propping up first the government of Hugo Chávez, and now that of Nicolás Maduro. Chinese economic and technical assistance has empowered and extended the lifespan of the Maduro regime, especially since 2019 when the U.S.-led “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign made Caracas dependent on China for a financial lifeline by offloading its sanctioned crude. Between 2020 and 2021 an estimated $3.5 billion of Venezuelan crude went to China, often making stopovers in third-party countries like Malaysia for refining beforehand.

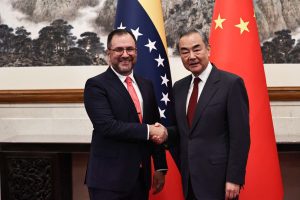

China has also emerged as one of Venezuela’s most important security partners, selling weapons like the above-mentioned K-8Ws, as well as the VN-4 armored personnel carriers infamous for their role in (literally) crushing anti-regime protests. Chinese telecommunications firms Huawei and ZTE have also been instrumental in helping Venezuela modernize its tools of digital authoritarianism and social control. Most recently, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yván Gil traveled to Beijing in early June, where he and his counterpart Wang Yi reaffirmed their shared commitment to an “all-weather strategic partnership.”

By contrast, in Guyana, China’s expanding influence has consistently cloaked itself with the white glove of “win-win” economic partnership. Chinese firms have won contracts to build new transportation and energy infrastructure throughout the country. Chinese state-owned enterprises have won contracts worth nearly $200 million to help modernize Guyana’s tourism infrastructure and railways, and have mulled the possibility of supporting the construction of a new deep-water port serving the oil sector. Guyana has also received Huawei-made security cameras complete with facial and license plate recognition capabilities in a move that drew concern from several Guyanese commentators around data privacy and storage.

Perhaps most significantly, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) possesses a 25 percent stake in the Starbroek oil block, co-investing with ExxonMobil (a 45 percent stake) and Hess (30 percent). The Starbroek block is both the source of Guyana’s recent economic windfall and one of the triggers behind Venezuela’s latest coercive moves.

Maduro has issued an ultimatum to all oil companies active in the disputed maritime territories. While CNOOC CEO Zhou Xinhua claims that the company’s “current development area is in a location without any disputes,” as passions within Venezuela rise, some have criticized China’s continued economic partnership with Guyana. For the time being, CNOOC’s presence may play a moderating role, as Maduro seeks to avoid jeopardizing his crucial relationship with Beijing.

However, the Venezuelan military’s continued buildup along the border with Essequibo is raising the potential for escalation that spirals beyond either country’s ability to control. If the worst does come to pass and the crisis spirals into outright hostilities, it will be increasingly tough for China to remain impartial, at least without jeopardizing some of its financial interests.

Contrast this with the position of the United States, which has maintained a steady drumbeat of high-level delegations to Guyana since the onset of Maduro’s provocations. In recent months, officials including CIA Director William Burns, incoming National Security Director for the Western Hemisphere Daniel Erikson, and numerous Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) officers have all passed through Georgetown to reaffirm Washington’s commitment to regional stability. SOUTHCOM Commander General Laura Richardson has been a consistent advocate for closer U.S.-Guyana partnership.

U.S. commitments have gone beyond mere rhetoric as well, symbolized in both the recent flyover and U.S. efforts to help the Guyana Defense Force (GDF) modernize its armed forces and equipment. In 2023, for instance, the United States provided additional Bell-412 helicopters and a new patrol craft, augmenting the GDF’s limited aerial and maritime capabilities.

However, while this disconnect should put Beijing in a bind when it comes to its dealings with Georgetown, China-Guyana cooperation has in fact increased in the months following Venezuela’s sham Essequibo referendum. China has donated additional medical equipment to Guyana’s healthcare system, building on previous vaccine diplomacy efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 15, Guyanese President Mohamed Irfaan Ali met with Chinese Ambassador Guo Haiyan where he reportedly expressed support for increased investment from Chinese firms. Most recently, in response to flooding across Guyana, China has donated amphibious vehicles and rafts.

Furthermore, Beijing’s messaging appears to have been relatively successful in charting a middle course. Analysts have observed that Chinese state-owned media has sought to balance coverage between Venezuelan and Guyanese perspectives on the dispute, even referencing the ongoing International Court of Justice case. This is a notable divergence from how other autocratic governments have portrayed the crisis, with Russia in particular parroting Caracas’ rhetoric and offering its tacit support to Maduro’s annexation efforts, including launching a Caribbean military exercise involving the Russian, Cuban, and Venezuelan navies.

These incidents underscore the fact that while China may appear to be playing both sides of the Essequibo dispute, it remains too important of a partner for either Venezuela or Guyana to dispense with. A more robust U.S. strategy for engagement with Guyana is needed not only for Washington to better compete with China, but also to allow Guyana to engage on more even footing with both Beijing and Caracas.

A starting point for this strategy should be doubling down on U.S. core competencies in the security and defense sector. While recent moves to help modernize the GDF are encouraging, China has also made inroads in military cooperation with Guyana, having sold a Y-12 patrol aircraft and donated some $2.6 million worth of vehicles to the GDF and police since 2017. In fiscal year 2021, just 20 members of the Guyanese armed forces received training from the United States, none of them at U.S. service academies or regional centers. Meanwhile, year-over-year, dozens of officers of the roughly 4,500-strong GDF have received training in China.

As Guyana looks to modernize and upgrade its defense capabilities with a much-expanded budget for the GDF, the United States should be at the forefront in providing assistance through Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and International Military Education and Training programs.

Argentina’s recent purchase of F-16 fighter jets with FMF is a particularly instructive example here. The deal was the first time Argentina received equipment through FMF in more than 20 years, and was important in countering China’s efforts to increase defense ties by marketing its own fighters to Buenos Aires. Increasing FMF to Guyana is a clear avenue through which the United States can maintain itself as a defense partner of choice and help Georgetown to maintain deterrence against its neighbor.

Beyond security, the United States should leverage its development tools to compete with China on infrastructure and energy projects, where it has thus far been largely absent. Crucial to these initiatives will be the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which has been heralded as critical to spearheading the counteroffer to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. But the DFC’s reliance on World Bank country income classifications means it has limited ability to operate in Guyana, which was recently elevated to high income status as a consequence of its oil boom. This label overlooks still-dramatic income disparities within Guyana and developmental needs in the energy transmission, transportation, health, and sanitation sectors. A more ambitious agenda from the DFC for Guyana can pave the way to allowing U.S. companies to compete for contracts in these sectors instead of ceding them to Chinese firms.

Finally, the United States should work to shore up the Argyle Accords signed by Venezuela and Guyana, committing the two to peaceful resolution of disputes regarding Essequibo. Drawing attention to Venezuela’s escalatory rhetoric and compellence strategy toward Guyana is critical to demonstrate the international community is watching and invested in maintaining interstate peace in the region.

Sustained U.S. attention and support will also help to demonstrate the contradictory approach China has taken, and reinforce the value of the U.S.-led rules-based international order at a time when such support is under pressure from all corners. Indeed, failure to maintain extended deterrence against Venezuela will carry far-reaching implications for all countries counting on Washington to support them in the face of pressure by revisionist powers.