This summer, I returned to China after nearly a decade to conduct fieldwork among Tibetan communities in Sichuan Province. As a scholar of Chinese and Tibetan culture who has spent significant time in China over the past two decades, I have had the opportunity to observe the transformations as Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping has centralized power and revitalized Chinese nationalism.

New, tightened restrictions became especially apparent on this most recent research trip, during which the government unexpectedly re-routed me from my Tibetan fieldwork sites. Instead of my planned research itinerary, I was led on a three-week tour of Yunnan Province by a CCP tour guide, who encouraged me to take the opportunity to “learn about the full richness of China’s many other minority groups.”

Throughout this spontaneous new itinerary, I was blocked from any meaningful encounter with Tibetans and instead shown a sanitized simulacrum of minority culture in the form of plays, theme parks, and other government attractions aimed at tourists from the Han majority ethnic group. In the new China of Xi Jinping, the cultures of China’s 55 ethnic minorities have been turned into a simulated commodity for domestic tourists under the guise of economic development and cultural preservation. Meanwhile, actual expressions of ethnic identity are suppressed.

While this process has been underway for some time, the transformation was accelerated during the pandemic by the deployment of facial recognition software and greater police-state observation. The realities of domestic Han tourism in the new context of the 21st-century Chinese police state have produced an invisible wall that sequesters minority culture and ultimately silences or otherwise obscures minority voices.

An Unexpected Change

Shortly after arriving in China – and the day before my husband and I were supposed to begin driving from Chengdu toward the city of Derge – the company we had worked with to arrange our travel called an emergency meeting. The owner explained that the CCP tourism bureau had barred our travel to the Tibetan regions of western Sichuan due to “floods.”

After a tense conversation in which I suggested a myriad of other routes or itineraries, it became apparent that anywhere ethnic Tibetans lived in Sichuan or Qinghai province had “floods.” Past experience had taught me that rhetorical games like this were a common tactic used by the Chinese government to deny access to people and places without explicitly saying “no.” Proving this point, I later confirmed that many foreign tourists had visited these regions during the summer. There were no “floods.” Either I had specifically been “graylisted” – allowed to enter China, but unable to go to any sensitive areas – or all foreign researchers like myself were barred from entry to Tibetan regions.

After scrubbing my research trip, the company offered a three-week trip through Yunnan, designed in consultation with both the national and provincial tourism bureaus. The next morning, our primary tour guide introduced herself as a CCP member who did not work for the company, but had been specifically asked to help culturally interpret for us on the trip. We traveled on a classic Yunnan tour that began in Kunming, and traveled through Lijiang, Dali, and Shangri-la, before eventually returning to Chengdu via Xichang.

While I was unable to do my planned research, the trip proved an eye-opening experience on how Han Chinese perceive and interact with minority culture.

Commodifying Minorities

The itinerary led us to a variety of sites created, primarily, for domestic Han tourists to experience China’s ethnic minorities. Among these was the Yunnan Minorities Village in Yunnan’s capital city of Kunming – a modern version of a “human zoo.” In this sprawling park, each of Yunnan’s 26 ethnic minorities has a pavilion showcasing their traditional homes, temples, and village life. Han guests are invited to interact with local representatives of the ethnic minority, each dressed in the most exaggerated representation of their traditional garb.

Especially popular with Han tourists are the performances, where a minority ensemble stages exuberant demonstrations of their traditional dances and songs. The emcee of each performance referred, in Mandarin, to the Han guests as “friends” (朋友) and invited everyone to dance along with his performers, often while making jokes to the audience about the simplicity of life in the minority villages outside the big city.

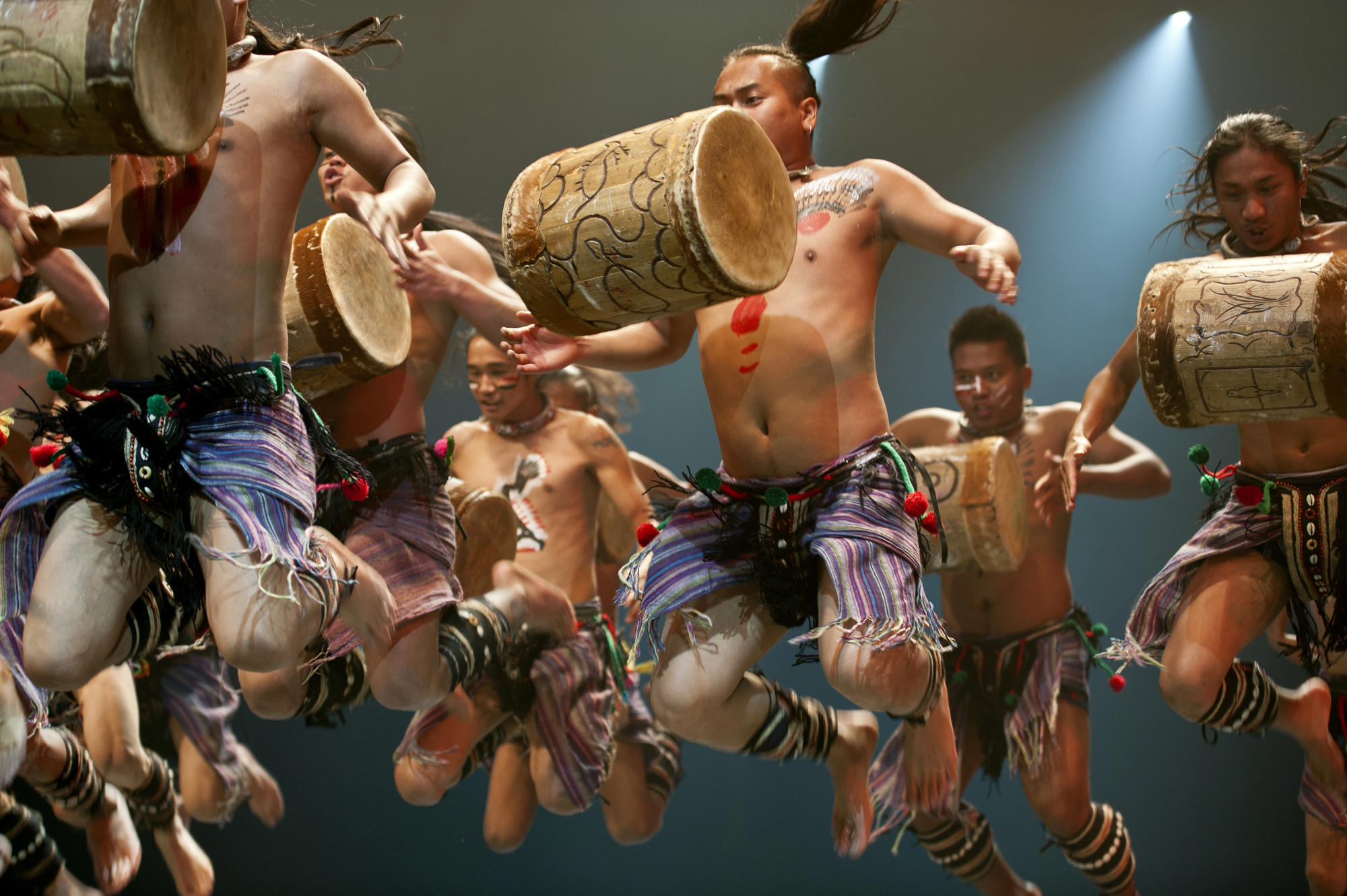

These dance experiences were echoed by other performances in Kunming, including the sold-out “Dynamic Yunnan.” Created by celebrated Bai minority dancer Yang Liping, the show claims to preserve dying forms of minority dance in an extravagant two-hour performance featuring hundreds of dancers, drummers, moving set pieces, and high-end lighting. The performance depicted minorities as alternately highly sexualized or deeply childlike, reflecting the “noble savage” trope ubiquitous in early Western anthropological literature. A shirtless drummer wearing only a loin cloth and drumming a song representing the sexual union of men and women was followed by a gaggle of minority women dressed as young girls making flirtatious gestures with their hands.

Dancers perform in a “Dynamic Yunnan” show at Jincheng Theater in Chengdu, China, October 27, 2011. Photo via Depositphotos/jackq.

Despite its lauded claims to support indigenous dancers, I noted that only a few select minority groups were represented among the dancers. Such a distinction is not entirely surprising. Scholars like Colin Mackerras have noted that certain minority groups receive significantly greater government support and funding in the preservation of their performance traditions; these resources often are inversely related with the perceived threat of separatism the minority culture may represent.

Sometimes this leads to minority communities being written out of their performance tradition entirely. When the Beijing Dance Academy celebrated its 70th anniversary this fall, clips circulated on social media of the predominantly-Han faculty and staff performing traditional Tibetan folk dances as part of China’s dance heritage. I noted that Dynamic Yunnan’s dance representing the Tibetan people featured no ethnic Tibetan dancers and ultimately portrayed a community obsessed with Buddhist devotion and religious practice to the detriment of all else, including financial livelihood and personal health.

The mostly Han audience, seemingly unreflective or unconcerned by the stereotyped performance of Dynamic Yunnan, gave several standing ovations. After the performance, our driver told us that “before minority people can walk, they are dancing; before they can talk, they are singing.” While seemingly an innocent expression of appreciation for the vitality of minority culture, aphorisms like this reinforce a narrative of childlike innocence preserved only through the power and benevolence of the (Han) Chinese government.

I asked our tour guide if a member of an ethnic minority might one day rise to the level of CCP general secretary. At first, the question itself confused her, and I had to keep repeating it in differing formats. Eventually, however, she just shook her head and told us “no.”

As we drove further into Yunnan province from the capital city of Kunming, the widespread effects of China’s domestic tourism agenda became more apparent. Each small village we stopped at boasted an “ancient town” – a pedestrian pavilion designed to appear as a charming relic from an antiquated time – filled with stores owned by Han transplants selling identical factory-made knickknacks. These ancient towns are the product of “folklorization,” wherein the particularities of a (minority) culture as it has historically been lived in a certain place are simplified into little more than a stylized picturesque photo opportunity.

And, indeed, photo opportunities did abound. Ancient towns bustled with young Han women who had rented minority costumes to walk around the picturesque setting. Many had hired photographers – usually local, minority men – to take dramatic photos of them as “tribal princesses” for sharing on social media. In Shangri-la, a historically Tibetan town that was renamed by the provincial government in 2001 to match the fictional paradise depicted in James Hilton’s 1933 novel “Lost Horizon,” I watched one such “tribal princess” unsure what to do with the Tibetan prayer wheel she had been handed as part of her costume. Continually tossing it in the air and trying to catch it again, she seemed uninterested in engaging with the Tibetan culture around her any more than necessary for the photo.

Smithsonian Institute folklorist Peter Seitel identifies this disinterest as a crucial feature of “folklorization.” When folklorized products and cultures are understood to be “other” to a dominant culture they are rendered “not as complex or meaningful as the products of high, elite, or official cultural processes.” Such items, therefore, are viewed as little more than a prop for photos.

The Policing of Minorities

The replacement of minority culture with a government simulacrum is aided by the startlingly effective use of facial recognition and virtual monitoring software to further isolate individuals from authentic relationships with minority peoples. After the government changed our itinerary, I immediately messaged my research contacts and friends on WeChat, the ubiquitous social media app popular in China. Explaining our experience honestly in writing over a virtual network, however, could raise the attention of an observation bot or a Public Security Bureau (PSB) officer and put my contacts in danger.

As a result, we had very coded conversations, where any significant communication had to be hidden between the lines of pleasantries. After explaining that it was “unsafe” to travel to western Sichuan due to weather and that I was disappointed that I could not see my friends, they assured me that “Yunnan is beautiful this time of year.” I understood with this message that there was nothing that could be done to get me to my fieldwork site.

While I’ve always had some concerns about observation while traveling in China, my fears were more pronounced on this most recent trip. On July 1, 2024, China introduced a law that PSB officers and border agents can look through laptops and cellular phones without a warrant. Knowing that I had potentially already been graylisted and could be under special scrutiny, all texts, social media posts, and emails had to be circumspect and speak in shadow language lest a PSB agent pick up any concerning words or phrases at a casual glance.

In practice, this took the unlikely form as encoding my research notes during travel in the form of a “Dungeons & Dragons” adventure, where an adventuring party (my husband and I) traveled through a potentially hostile place (the Vagosi Empire) to learn about a small minority culture (the Erinvale tribe). I hoped the language of swords and spells might confuse a PSB agent looking for a specific list of banned topics.

Similarly, China’s lauded facial recognition software became a constant source of anxiety whenever I spoke with Tibetans and other minorities. Because my husband and I were Americans, some individuals I met on our tour felt comfortable sharing candid thoughts about the CCP government, the political situation for minorities, or the limits on religious freedom that have become normalized in China. In previous times, such conversations would become important parts of my research highlighting the lived practice of minority religious life in China.

While writing my research notes, however, I realized how the new facial recognition software meant that it was impossible to fully anonymize my conversation partners. As a result, I could never discuss their experiences or share their voices in my research. In these ways, just the threat of the Chinese police state’s powers creates a form of self-imposed isolation that not only achieves their goal of silencing criticism, but also bars those outside of China from hearing authentic experiences and opinions from minority cultures.

Conclusions

After three weeks of travel through Yunnan, I was denied access to actual minority culture and instead shown a state-approved rendering of minority cultures. These simulacra are built for an audience of Han tourists and promote the distorted image of a unified, multiethnic China. Previously China’s ethnic minorities had enjoyed some agency in how they presented themselves and the freedom to express authentically their own culture, but as we toured staged “ancient towns” and sat through stylized minority dance performances, it was apparent this was the minority culture China wanted us to see.

In her work on state-led economic development among ethnic minorities in China, Charlene Makley has described the “silent pact” between Tibetans and Han Chinese in the People’s Republic of China. By remaining silent on the complex histories between the two communities and the implications inherent to competing structures of religious and political authority, both communities have been able to maintain an uneasy peace that provides the ground for mutual economic prosperity, at least in theory. Such a pact exists between many ethnic minorities and the CCP government. My trip demonstrated, however, that this unspoken arrangement has also laid the groundwork for a more insidious transformation of culture. No longer is it only political and religious histories that are not being discussed, but authentic cultural self-expression as well. Where the silent pact had existed previously, there now was a silent wall.

In a cruel twist of timing, my travel coincided with the closure of one of the last remaining private Tibetan schools – a bastion of Tibetan culture and one of the very last places in China where classes could be taught, at least in part, in the Tibetan language. Some social media commentators called it the start of a “second cultural revolution.” Among my colleagues who study Tibetan culture, there have been quiet discussions of looking for new research sites outside of China that are less politically volatile. We have the privilege to make that decision, but it only leaves Tibetan friends and colleagues within China further isolated.

The night I discovered I would be unable to pursue my fieldwork, I lay awake obsessively digging through my past to try and understand what might have made me problematic in the eyes of the Chinese government. Was it that article I published using social theory to highlight how the CCP was secularizing Tibetan culture to serve the needs of a multiethnic state? Was it the conference I attended in Dharamshala at which the Dalai Lama had unexpectedly been a guest? Was it the blog article I shared on my social media about the protests in Derge aimed at protecting several important Buddhist monasteries from a planned hydroelectric dam?

Above all, my mind kept returning to my friends and Tibetan colleagues trapped behind the new silent wall of the Chinese police state. As an international student at Tibet University early in my academic career, I had watched Tibetan friends gathering every Friday night to dance together the traditional circle dances from their home villages. Those memories remain for me a powerful expression of a people working to maintain their traditional culture in a hostile environment. Now, 15 years later and staring at the ceiling of a Chengdu hotel room, I wondered to myself if they were still dancing on that night – not for Han tourists or white friends stumbling through conversations in broken Tibetan, but for themselves – desperately fighting to preserve their culture as a government sought to box it ever more into a neatly packaged commodity.