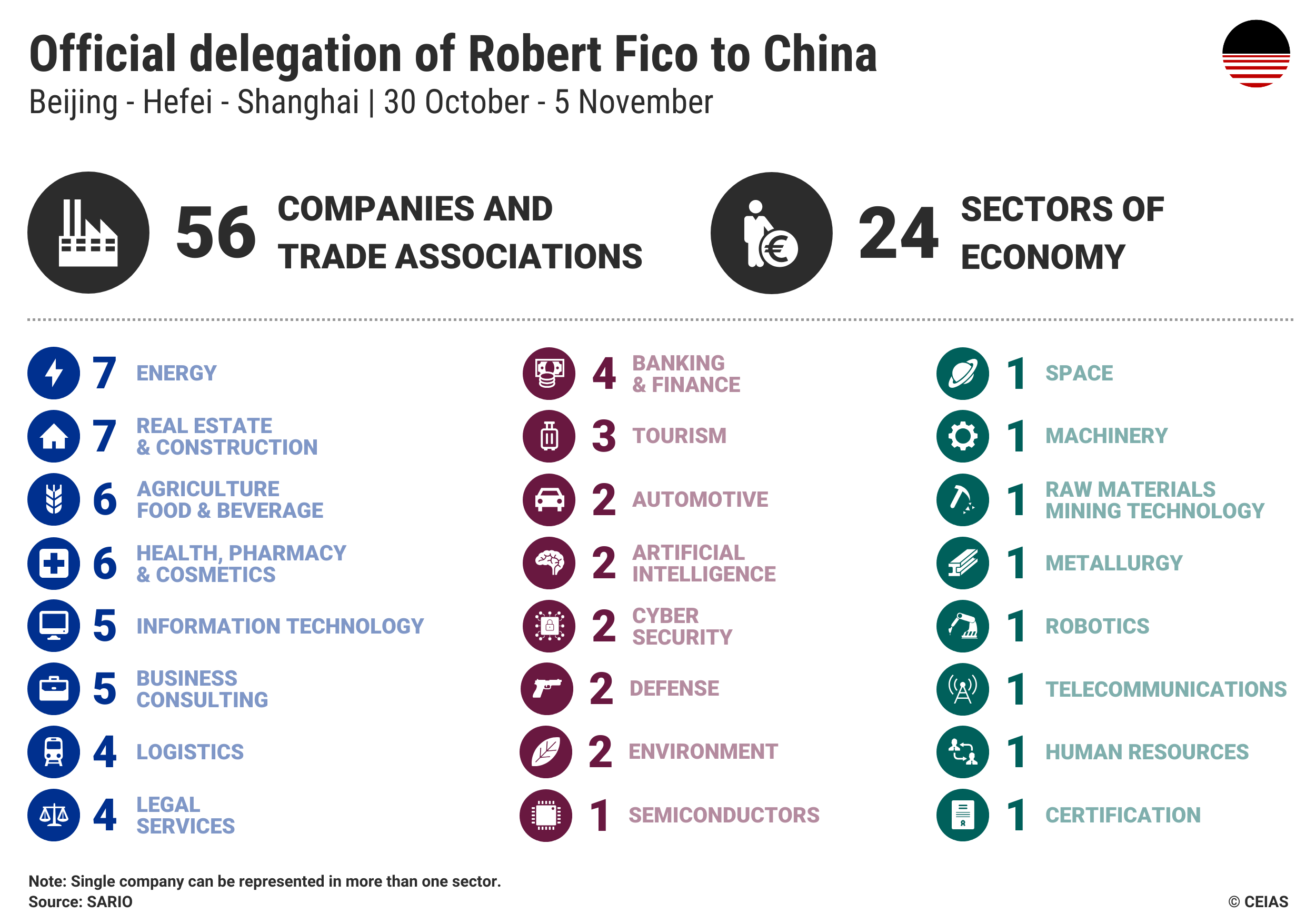

Between October 31 and November 5, Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico paid an official visit China. Fico was accompanied by an unusually large delegation, which included eight cabinet ministers, two deputy ministers, and representatives of 56 Slovak companies and business associations. The delegation visited Beijing, Hefei, and Shanghai, joining in for the kick-off of the China International Import Expo in Shanghai.

The visit took place under a veil of non-transparency, as very little information was available about it prior to the delegation’s departure from Slovakia. This was made worse by the fact that no journalists were permitted to accompany the prime minister.

Fico, whose original plans to visit China in June were postponed due to an assassination attempt, lauded the trip as “the most important visit of the year.” In a larger context, the Slovak leader touted his China visit as evidence of the “all-azimuth diplomacy” that he has professed to lead since returning to power in the fall of 2023.

This framework is a euphemism for a policy of naive pragmatism that strives to build economic relations with any country, regardless of political regime and values, or the security implications and broader geopolitical ramifications. Fico’s government has promised to reinvigorate economic diplomacy, and even rebuild the relationship with Russia. In this way, Fico has sought to keep the support of his part of the electorate, which is skeptical toward Brussels and Washington and disgruntled with the support for Ukraine, and favors Slovakia going its own way.

While short on concrete results, the high-profile visit was symbolic of Slovakia’s turn toward China, illustrating the trend of China getting more friends in Europe in a crucial time of geopolitical transformation.

Strategic Partnership

The most significant political result of the visit was the signing of a bilateral strategic partnership between Slovakia and China. Slovakia has been a laggard in terms of politically upgrading its ties with China to a strategic partnership level, which also serves as a designation used by China to “rank” its ties with foreign countries. Now, only seven European countries (Sweden, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovenia, and the Baltics) remain without an official designation for their relationship with Beijing.

At the same time, most of the existing partnerships were signed in a very different geopolitical context in the 2000s and 2010s. Beijing most recently upgraded its strategic partnership ties with Hungary and Serbia, the two closest partners of China on the continent, earlier this year. Thus, even if it is not exceptional for Slovakia to have established such ties with China, the timing and wider context speak volumes. For his part, Fico tried to legitimize the move by comparing it to recently concluded strategic partnerships with Japan and South Korea.

In general, the strategic partnership text outlines the framework for further cooperation, including the establishment of an intergovernmental commission for cooperation. Two things stand out in the document. First, the document states that the two countries “firmly oppose the politicization and instrumentalization of human rights issues, and firmly oppose any country interfering in the internal affairs of other countries under the pretext of democracy and human rights.

While some formulation of the norm of non-interference is common in such documents – e.g. the strategic partnership with neighboring Czechia from 2016 – the explicit echoing of China’s stance on human rights issues, which relativizes what should be universal rights, is worrying. However, it fits very much with the tenets of the “Ficoist” foreign policy, which, as praised in a surprisingly direct way by China’s Global Times, “advocates for abandoning value-based diplomacy.

The second wording of interest is Slovakia’s stance on Taiwan. The document notes: “Slovakia reaffirmed its firm commitment to the one-China policy, that there is but one China in the world, and that the Government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole legal government representing the whole of China. Slovakia opposes any attempts to interfere in China´s internal affairs, sovereignty, and territorial integrity, including Taiwan.”

The specific reference to Taiwan in the document can be seen as an appeasing step by Slovakia. Under the previous governments in power between 2020-2023, Slovakia notably expanded ties with Taiwan, a move detested by China. It is worth pointing out that, before Fico’s visit, the Chinese ambassador panned Slovakian opposition politicians for their support for “Taiwan independence” while praising Fico’s stance. So Slovak diplomacy might have considered it to be important to reiterate its position.

Nevertheless, the statement in the strategic partnership document is actually in line with previous official statements. In 2003, during the visit of then-President Rudolf Schuster, Slovakia also committed to an interpretation of the One China policy that closely copied China’s stance on the issue, though in practice Bratislava maintained a more open approach toward Taiwan.

Slovak and Chinese representatives also found alignment in their thinly-veiled pro-Russian views of the invasion of Ukraine. Fico expressed that he fully agreed with the Chinese position on the war, and expressed support for the Chinese peace plan, which strongly favors Russia. It is not the first time Fico expressed this sentiment. Already in February 2023, when China presented its 12-point policy paper, Fico and his colleagues from the SMER party discussed it with the Chinese Embassy and even organized a press conference to promote it in Slovakia.

Economic Cooperation

While Fico presented his visit with great fanfare, there have been no actual deliverables in terms of economic cooperation. Altogether 13 memoranda of understanding (MoUs) were signed by the two sides.

Official communication from the Prime Minister’s Office highlighted two outcomes as key deliverables of the visit: the extension of China’s visa-free regime to Slovakia, and investment by Gotion into battery production in Slovakia. Other initiatives were touched upon during the visit, such as cooperation on transport and energy infrastructure development in Slovakia, but very few specifics are available for now. Some of the proposed projects, like the power plant on the Ipeľ river and the direct air route from Bratislava to Beijing, are mainstays of the Slovak proposal to China, with Beijing showing little interest in picking them up over the past decade.

Per Fico, the extension of the 15-day visa-free travel to China for Slovak citizens is a “significant result” of the trip. However, the significance of this development is rather undercut by the fact that 18 European countries had already been granted visa-free access, and Slovakia was included in a batch of six more countries, including Andorra and Monaco – none of which needed to send over a delegation comprising half their cabinets to secure the privilege. On the contrary, receiving the visa-free regime was the bare minimum expected from such a high-profile visit. China is currently on a giving spree when it comes to visa-free travel, as it aims to restart its tourism sector and provide a boost to its economy.

The second outcome of the trip lauded by Fico is the EV battery greenfield investment by Gotion. However, by highlighting this investment as a major outcome, Fico has, in essence, confirmed that his trip did not have very specific aims and that its outcomes were rather underwhelming. Fico’s government already signed an MoU with Gotion about its investment plans back in November 2023, less than a month after the government was formed.

The project, together with another big Chinese investment, the Volvo EV plant in Košice, was actually negotiated during previous administrations, which were much more critical toward China. This actually underscores that a wary approach to China, one conscious of security considerations and political values, is not necessarily detrimental to economic cooperation, especially on projects that follow economic logic, rather than political wishes.

Moreover, under the Belt and Road Initiative, which Slovakia “acceded” to back 2015, the only specific project mentioned was cooperation on the China-Europe Express, the railway connection to China. Slovakia has long sought to profit from the rising traffic of freight trains between China and Europe. However, even before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Ukraine-Slovakia corridor saw little use, and a vast majority of rail transport on the Asia-Europe corridor has continued to flow through Belarus and Poland.

Even if no new projects were concluded, the visit was indicative of the Slovak government’s and business community’s dismissal of economic security concerns in cooperating with China.

Among the 56 businesses accompanying Fico on the trip, several are active in sectors considered sensitive or strategically important. The delegation included, among others, companies related to nuclear energy, defense, semiconductors, telecommunications, cybersecurity, or artificial intelligence. These are also some of the fields in which Slovakia and China pledged to deepen research cooperation, which would lead to increased exposure of Slovak academia to China. Meanwhile, the appetite to implement a robust research security framework has all but stalled.

In light of the Slovak government’s decision to move forward with the construction of a new nuclear reactor, the presence of the Slovak Nuclear Energy Company (Jadrová energetická spoločnosť Slovenska, or JESS) is of concern. JESS is a semi-state-owned company tasked with the construction of new nuclear power plants in Slovakia. It is a joint venture between state-owned enterprise JAVYS and ČEZ Group, a Czech semi-state-owned energy company. While the government has publicly expressed interest in working with South Korean technology suppliers, the project’s details – including its financing – remain murky for now.

Given Fico’s openness to work with Chinese companies on various other infrastructure projects, we need to ask what the purpose of JESS’s participation in the business delegation was, and whether it is considering using Chinese financing for the project of the new nuclear plant.

Another highly problematic agreement was a cooperation and content-sharing deal signed by TASR, a public press agency, and China Media Group, a national media house under the direct control of the Chinese Communist Party Propaganda Department. As TASR is used as a source for basic news reporting by a majority of Slovak media, this deal exposes a large share of the Slovak media space to the potential spreading of propaganda and disinformation, especially when it comes to reporting about China itself, or issues that China would consider its own core interests.

Future Prospects

Overall, Fico’s approach to China is largely a departure from the pre-existing approach, which tended to follow the European Union’s policy of seeing China simultaneously as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. This was enshrined also in the 2021 National Security Strategy, a document that viewed China largely through the prism of economic security: “China is significantly increasing its power potential and political influence underpinned by rapidly growing military capabilities, which, combined with economic power and strategic investments, it is assertively using to advance its interests.”

Fico’s trip to China and his views of the country form quite a contrast with this.

As noted by Chinese scholar Wang Hongyi in the Global Times, “strategic proximity between China and Slovakia has a demonstrative effect on shaping a healthy, de-ideologized and de-geopoliticized relationship between China and Europe.” Having Slovakia as another friendly voice in Europe can be helpful; even if Bratislava is a minor and increasingly isolated actor, it is still able to wield veto power in key foreign and security policy decisions on the EU and NATO levels.

Is China thus gaining another Viktor Orbán in Fico? It might be too soon to tell.

So far, Fico has been more reserved on the European stage, and has tried to avoid putting himself in the same ostracized position as the Hungarian prime minister. This position started to crack, though, during the discussions on countervailing duties against China-made electric vehicles. Fico explicitly went against the European mainstream thinking and vocally condemned the EU Commission for “starting a trade war with China.”

As Fico sees more benefits from engaging China, both from the perspective of burnishing his domestic credentials as a proponent of “sovereign” Slovak foreign policy and a successful agent for Slovak economic interests, he might lean even more toward Beijing.