In September 2024, a Soyuz rocket blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome en route to the International Space Station (ISS). Aboard were two Russians and an American. Given the depths to which relations between Russia and the West have sunk in recent years, it’s remarkable that cosmonauts and astronauts continue to fly together. Perhaps their blast off from Baikonur is appropriate: for over three decades, this rented piece of land in the middle of the Kazakh steppe has been a place where earthly compromises are made to satisfy galactic ambitions.

That said, while the septuagenarian space port proves as reliable as ever, geopolitics and funding mean that its future at the forefront of space exploration is far from guaranteed.

Glorious Isolation

A three-hour flight from Moscow, and hundreds of kilometers from even a minor urban settlement, Baikonur was chosen as the site for the Soviet Union’s missile development program in 1955 precisely because of its inaccessibility. It wasn’t until 1957 that an American U-2 spy plane learned of its existence.

The cosmodrome was the site of humanity’s first great achievements in space – the first ICBM launch (1957), the first satellite in space (Sputnik, 1959), and the launch pad for Yuri Gagarin’s successful quest to become the first man in space. Baikonur remained at the heart of the Soviet space program for decades, before becoming part of the Republic of Kazakhstan in 1991. However, such was its value to Russia, and given that Kazakhstan had no immediate plans for a space program of its own, the Kremlin negotiated to lease the site.

Russia wanted a 99-year lease on the spaceport, but the Kazakhs bid them down to an initial period of 20 years, which was later extended until 2050. Russia pays Kazakhstan $115 million a year, which buys it the cosmodrome, with its 13 launch pads and its ICBM silos, as well as surrounding territory with a diameter of around 90 km.

Source: Public domain

Integration into the International Space Sector

The USSR’s collapse did little to diminish Baikonur’s importance to global space research. In fact, it paved the way for the increasing internationalization of the space port. In 1993, U.S. President Bill Clinton invited Russia to become a part of the ISS project, and Baikonur remained a key launch site for manned missions to space.

Indeed, in every year between 1990 and 2016, it was the world’s busiest space port. Between the retirement of the American Space Shuttle in 2011 and the first successful crewed mission aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in 2020, Russian Soyuz rockets launched from Baikonur were the only way for humans to reach the ISS. Roscosmos, the Russian government space agency, quickly exploited this, charging up to $90 million per seat. In total, they made $3.9 billion from ferrying 70 foreign astronauts up to space between 2006-20.

The Green Grass of Home

All the same, Russia has long desired to reduce its dependence on Kazakhstan. It has a spaceport for military satellites in Plesetsk, 800 km north of Moscow, and since 2007 has been working on the construction of the Vostochny Cosmodrome in the Amur region of the Far East.

“The purpose was clear: Russia was going to be independent from Kazakhstan in outer space activity,” says Pavel Luzin, visiting scholar at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. “That means Russia can withdraw from Baikonur even earlier than the term of the lease contract.”

Vostochny has got off to a slow start. Its development has been fettered by corruption scandals – in 2018, prosecutors claimed that over $150 million had been embezzled from the project.

Nevertheless, Vostochny saw its first Soyuz launch in 2016, and there was immense relief when, this April, Roscosmos achieved a successful launch of its new generation Angara heavy rocket on the third attempt.

“The nerves of all Russians were frayed,” said the head of Roscosmos, Yuri Borisov, in a recent interview with TV channel RBK. “This indicates that real infrastructure for launching a heavy carrier has been prepared and tested at Vostochny. This is a serious step.”

Yet Russia’s eastern cosmodrome is unlikely to replace Baikonur in the short term. The old space port has significant advantages, especially for manned missions into space.

The first is Baikonur’s lower latitude: given that the earth is rotating faster the nearer you are to the equator, rockets tend to be launched as close to the equator as possible to take advantage of the free “speed boost” that this rotation offers. At the equator itself, the earth is rotating at 1668 km/h. The boost confers significant fuel savings and in turn allows spacecraft to carry heavier payloads; this is why U.S. space launches take place in Florida, California or Texas, and the European Space Agency launches from French Guiana.

Nowhere in the Soviet Union was particularly close to the equator, but Baikonur, at 45 degrees north, is closer than anywhere in Russia.

Manned space flight is also an immensely risky endeavor, and Soyuz rockets launched from Baikonur have proved over the decades to be the most reliable way of delivering humans into orbit.

“It’s not easy to immediately develop the absolutely new infrastructure for launching rockets. [Vostochny] is a long term and very expensive project of Russian government,” says Stanislav Pritchin, head of the Central Asia sector at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO), Moscow. “On the other hand, Baikonur has quite developed infrastructure. Everything is working, it’s ready.”

The entire ISS program has been optimized around launches from Baikonur.

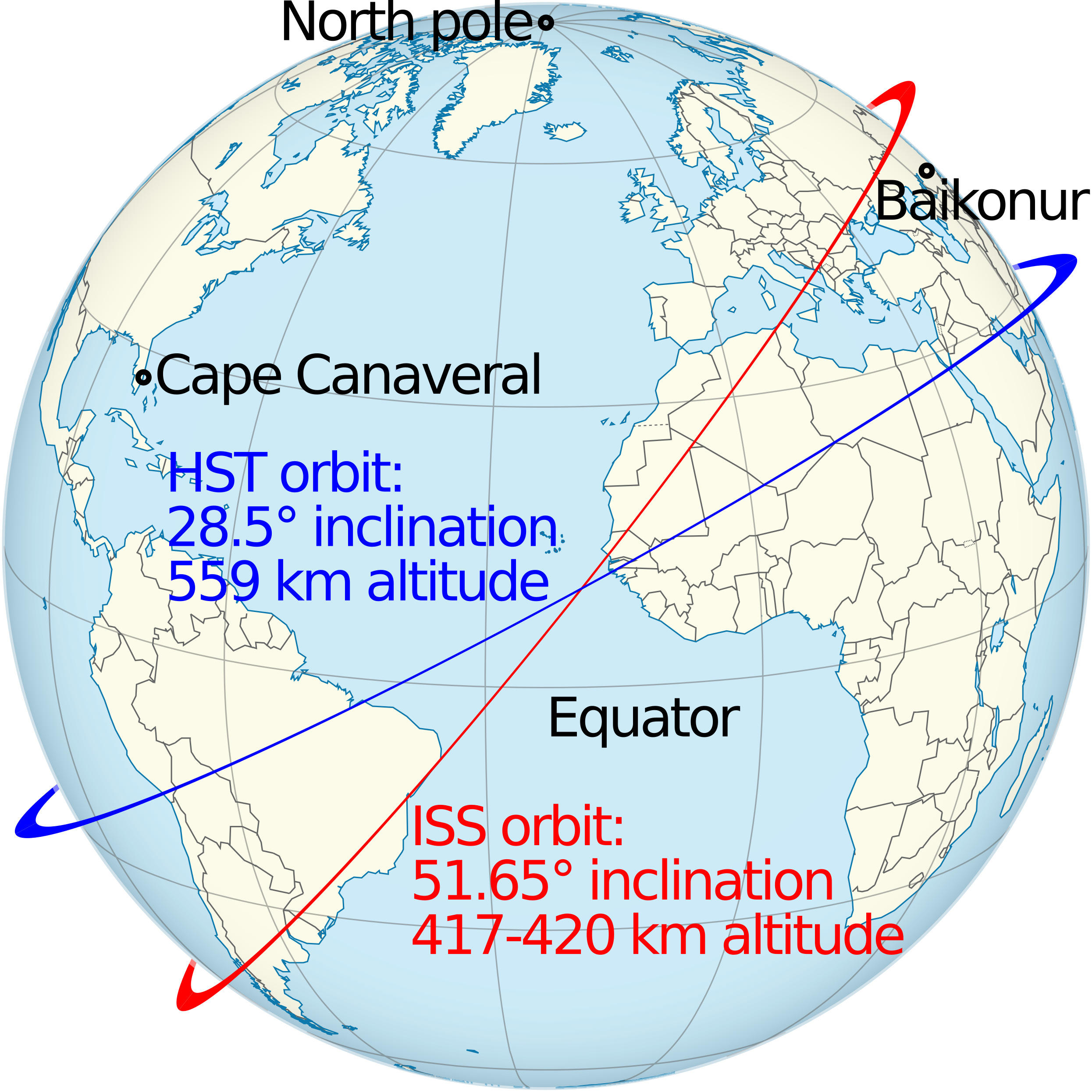

“The ISS orbit was designed because of the Baikonur and Kennedy Space Center locations,” says Luzin.

The ISS orbits the earth at an inclination of 51 degrees, slightly higher than Baikonur, which means rockets usually launch to the northeast. It has been designed this way as a direct eastward trajectory would see the rocket boosters jettisoned over China.

Source: Wikimedia Commons / TUBS, Luan

Cooperation Breakdown

But the missions to the ISS will not go on forever. The U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) plans to leave the station by 2030. There were fears that the war in Ukraine might put the project at risk even sooner than that. Shortly after the invasion began, the former Roscosmos chief, ultranationalist motormouth Dmitri Rogozin, threatened that Russia would pull out of the ISS program all together. However, those fears did not materialize, and NASA did its best to rise above the politics. When one of its astronauts, Scott Kelly, got into a Twitter spat with Rogozin, Kelly was reined in by the head of the space agency, Bill Nelson, who said that “attacking our Russian partners is damaging to our current mission.”

Perhaps Moscow too realized that Rogozin had gone too far. He was shunted aside, given a new role as senator for the amputated Zaporizhzhia Oblast in Ukraine currently under occupation by the Russian military; the same day, Russia and NASA agreed on a seat swap where Russian cosmonauts could fly on U.S. craft, and vice versa.

The new head of Roscosmos, the less bellicose and more put-together Yuri Borisov, said in the interview with RBK that Roscosmos now plans to remain on the ISS until 2030.

“The teams of American and European astronauts together with our cosmonauts carry out experiments very amicably, despite the political situations that have developed over the years. For them, [the geopolitical tension] does not exist,” he said.

Such close cooperation between Russia and the United States is nevertheless surprising, particularly as the U.S. is not open to cosmic cooperation with everyone: the 2011 Wolf Amendment prevents any bilateral cooperation with China in space without congressional approval.

That said, perhaps this reluctant cooperation says more about the uniqueness of the ISS. Both countries are already looking beyond it. Russia currently plans to build its own orbital space station, with Borisov promising the launch of the first module by 2027.

“In 2030, it will already be visited, inhabited, and astronauts can fly in and conduct experiments,” he said, promising that it would be fully complete in 2032.

Financial Troubles for Roscosmos

The launches for a new Russian station are all slated to take off from Vostochny, but some are skeptical about Russia’s chances of pulling off such a project. “It’s not clear whether Russia is capable of making this station,” says Luzin.

Roscosmos has endured a difficult decade. An oil price crash, a pandemic and now war have seen its budget plunge in dollar terms from $5.17 billion in 2013 to an approximate $2.85 billion in 2024. This is set to be reduced further to $2.58 billion by 2026. It has also had to adapt to a world where increasingly stringent sanctions are undermining its access to cutting-edge technology. The organization has sought to obfuscate its accounts to aid in the evasion of these.

Despite these obstacles, given the immense pride and status that Russians give to space projects, the Kremlin is extremely unlikely to abandon manned missions to space.

“We opened space to the world,” said Borisov. “Every Russian, at the genetic level, has a certain legitimate pride in our past achievements. This obliges us to do a lot today.”

Nevertheless, the danger is that the Russian space program, and Baikonur, could drift into irrelevance. Baikonur held the title of the world’s busiest space port in every year from 1990 to 2016, before being overtaken by Cape Canaveral. Since then, the world has seen a new “space boom,” which has since seen demand shoot up to such an extent that the Florida space port is struggling to accommodate new launches.

The success of the Space X Crew Dragon mission to the ISS in 2020 allowed the U.S. an alternative source of means of pursuing manned missions to space. Meanwhile China successfully launched its own space station – Tiangong – which became operational in 2021.

Baiterek

And what of Kazakhstan, where Baikonur is? Hope was placed in the joint Baiterek program between Kazakhstan and Russia, which envisaged the modernization of the launch complex at Baikonur to host next-generation Soyuz-5 rockets. After some wrangling in the middle of 2023, when Kazakhstan impounded a Roscosmos subsidiary company at Baikonur for failing to pay a $29.7 million debt to Kazakhstan, most of these issues have been ironed out. The idea is that, even if Russia moves to Vostochny, Kazakhstan will be able to independently compete with its own low-orbit launches.

“Russia wanted Kazakhstan to maintain close ties with Russia,” states Luzin. “That’s why the Baiterek project appeared in the early 2000s. Therefore, when Vostochny becomes fully operational and the ISS is deorbited, Baiterek will be the only reason to keep Baikonur. Though, the prospects for Baiterek are unclear.”

Pritchin is more optimistic. “I think that the Russian government, in any case, will try to prolong the agreement with Kazakhstan in order to continue to use the area while simultaneously developing our own program.” He adds that Russia will be keen to remain at Baikonur for its symbolic value. “Gagarin launched from here, launch pad number one is still there. Symbolically, it’s very important to use this infrastructure in the future.”

The modernization of Gagarin’s Start – the legendary launch pad from where man first blasted off into space has been put on hold due to lack of funding. Indeed, over the past several months, Kazakhstan and Russia have been discussing whether the Gagarin’s Start element of the cosmodrome can be withdrawn from the lease, and handed over to Kazakhstan for use as a museum, developing the site more generally into a tourist attraction.

Perhaps that is the fate that awaits Baikonur itself.