On December 8, a coalition of rebels led by Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) conquered Damascus, and President Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow. The same day, China mobilized 14 warships, seven military aircraft, and four balloons near Taiwan – 7,830 kilometres east of Syria. This may seem a ridiculous juxtaposition, but it illustrates precisely where Beijing’s strategic priorities lie.

It’s not that Syria is unimportant to China. However, performative politics have reinforced narratives that often overstate the country’s strategic significance to Beijing. Unlike Russia and Iran, which provided substantial military, financial, and political assistance to Assad since the civil war erupted in 2011, China’s support has been tepid.

Limited Economic Engagement

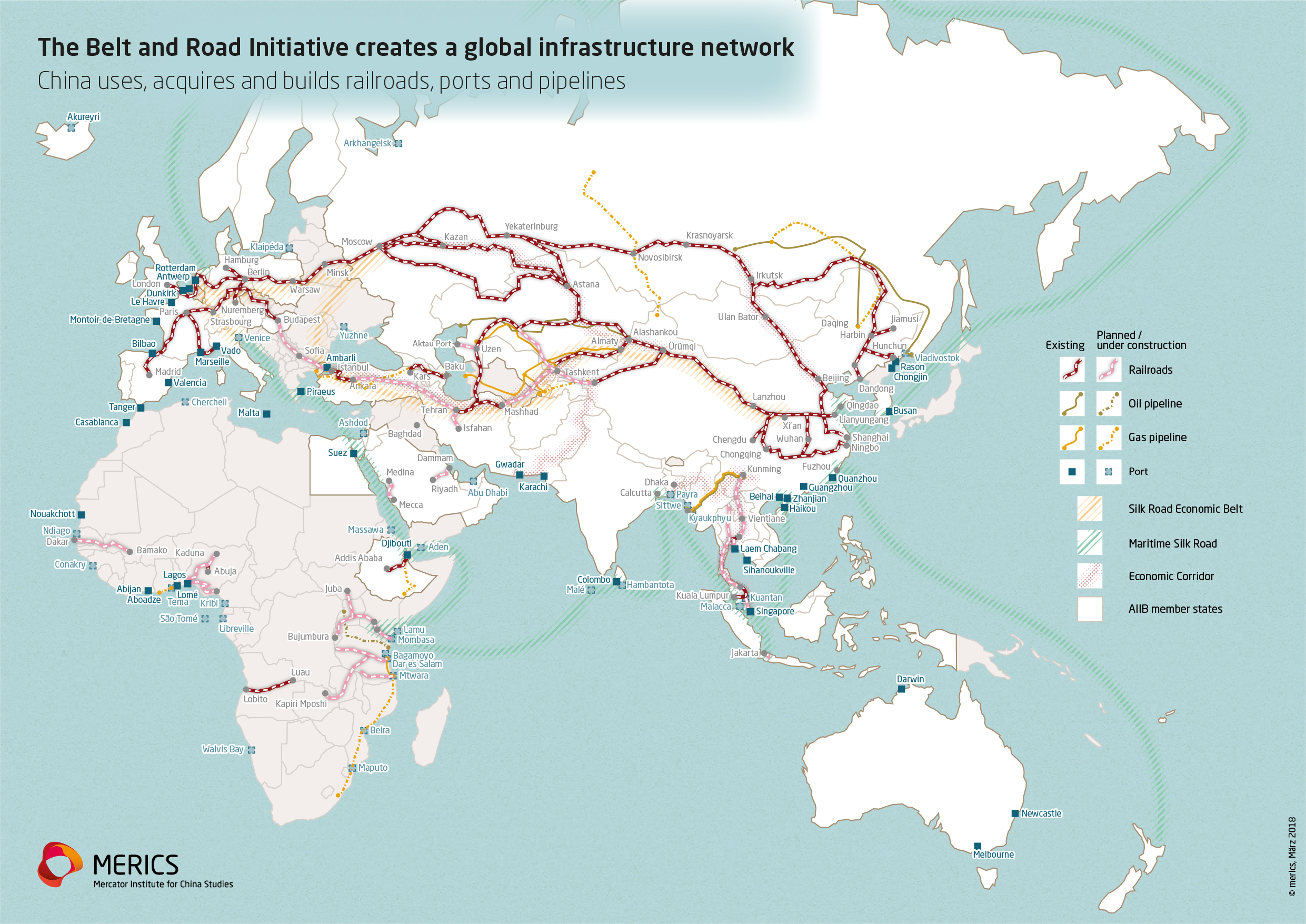

Assertions that China has become an important economic partner for Syria or that Syria represents some critical node on Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are not grounded in reality. A look at a map of the BRI reveals that none of the belts, roads, or pipelines ever planned to traverse Syrian territory. Claims that the port in Latakia is a critical node for China’s maritime Silk Road in the Eastern Mediterranean were, at best, always speculative.

MERICS’ map of the railroads, pipelines, and ports under the Belt and Road Initiative. Republished with permission.

According to the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, Chinese investments and construction contracts in Syria amount to a total of $4.6 billion – all of which were initiated pre-civil war. By contrast, Iran has provided between $30 and $50 billion in investment to Assad’s regime over the past 13 years.

In 2018, Chinese Ambassador to Syria Qi Qianjin penned a letter pledging to “strengthen our cooperation with Syria on the political, military, economic and social levels.” Yet since then China-Syria bilateral trade has plummeted at an annualized rate of 22.49 percent, dropping from $1.27 billion in 2018 to $356 million in 2023.

China’s endless promises of more trade, investment, and reconstruction in Syria have failed to materialize. Beijing pledged $2 billion in aid to Syria in 2017, and six years later, the media reported that the funds have “yet to materialize.” Meanwhile, the United States donated $2 billion in humanitarian assistance to Syria in 2023 alone, and has sent more than $17.8 billion since the start of the crisis. The EU mobilized more than 33.3 billion euros (around $35 billion).

Notably, when China offered Syria aid in 2022, it took the form of a grant to Assad’s regime to purchase telecommunication equipment. Beyond establishing a foothold in Syria’s telecoms sector, the integration of such technology into critical national infrastructure could, in theory, provide opportunities for signals intelligence.

China’s Political Support: Diplomat Posturing?

If it wasn’t already crystal clear, China’s support for Assad has always been about self-interest, not sentiment. Beijing opposes regime change on principle, fearing it sets a dangerous precedent that threatens the Chinese Communist Party. Meanwhile, the chaos that ensued in Libya in the wake of Muammar Gaddafi’s downfall only reinforced China’s “devil-you-know” doctrine.

That – and not any particular bond with Assad’s regime – explains why China used its United Nations veto powers in lockstep with Russia on some 10 occasions to shield Assad from sanctions, block International Criminal Court investigations, and oppose calls to end violence against civilians by the brutal dictator. Beijing even joined Moscow in abstaining from votes to extend approval for cross-border humanitarian aid, contradicting a practice key to its very own peace plan.

Chinese officials have leveraged the conflict, as they have many others, to undermine the United States and its allies at every opportunity, accusing Washington of infringing on Syria’s sovereignty, plotting “color revolutions,” and “plundering Syria’s resources.” At the same time, China endorsed Russia’s intervention under the pretense of Responsibility to Protect (R2P), a move driven partly by a pre-Ukraine invasion hope that Moscow would take on a greater role in Middle East security, providing a counterweight to U.S. influence.

When Xi Jinping hosted Assad in China in 2023 and the two signed a strategic partnership, it was more about diplomatic posturing than a reflection of Xi’s claims that “the friendship between the two countries” had “strengthened.” The visit appeared carefully choreographed to vindicate Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s 2023 assertion that Chinese diplomacy was driving “a wave of reconciliation” across the Middle East.

After all, earlier that year, Syria rejoined the Arab League, and China subsequently brokered some normalization between arch-rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran. During the visit, Assad made sure to praise Xi’s BRI, the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilization Initiative as harbingers of peace and prosperity. Yet for all the fanfare, there were no new investments or projects announced during Assad’s visit to China.

In a sense, Chinese diplomatic overtures have since been exposed for what they are: performative and opportunistic.

Cause for Concern

Make no mistake: China’s leadership is not happy about the fall of Assad. For one, it marks a setback for China’s Middle East diplomacy, with some analysts going as far as to suggest that it could inspire some re-evaluation of Beijing’s relationships with Moscow and Tehran.

More concerning for China is that the conflict might spill over and destabilize countries where China actually has significant interests. In countries like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or the UAE, China has billions in investment, trade, and infrastructure at stake. Beijing is also keenly interested in the security of critical maritime chokepoints like the Suez Canal, Bab al Manadab Strait, and Hormuz Strait, which China relies on for energy and cargo shipments.

Another looming issue, of course, is the presence of over 5,000 Uyghurs in Syria who have reportedly joined the ranks of the Turkestan Islamic Party – a Uyghur separatist group with origins in China’s western region Xinjiang that fought alongside HTS.

As Yang Xiaotong, an assistant researcher at a Beijing-based independent think tank, wrote, “HTS’ victory in the Syrian civil war does not pose an immediate threat to China.” However, “TIP militants gaining combat experience” certainly does.

While it would be challenging for TIP fighters to return to China, Beijing is worried about them joining other radical forces in Afghanistan and Pakistan – countries that share borders with China. Pakistan, which hosts China’s $65 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, is already struggling to provide security for related projects amid a surge of militant attacks.

According to media reports, the TIP released a video on December 8 in which fighters with machine guns threatened Beijing. “Now here in Syria, in all the cities here, we fight for Allah, and we will continue to do this in our Urumqi, Aqsu, and Kashgar in the future,” said one masked man, listing cities in Xinjiang. “We will chase the Chinese infidels away.”

What Next?

If history is anything to go by, China will wait for the situation to calm down before making any definitive maneuvers while closely monitoring the security situation. If Syria manages to get its house in order, Chinese diplomats can be expected to move swiftly to try to strike deals with whoever takes power in order to secure Beijing’s interests.

Given China’s support for Russia, Iran, and Assad’s regime, however circumspect, the next Syrian government may well harbor hostility toward Beijing. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that restoring ties with China will be entirely off the table. After all, no one really wants to rebuild Syria, do they?