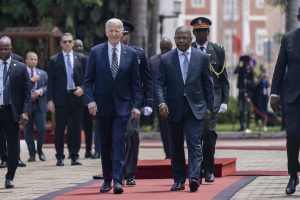

It’s finally happening: A U.S. president is visiting a country in sub-Saharan Africa for the first time in 11 years. President Joe Biden’s arrival in Angola comes two years after the second U.S.-Africa Leaders’ Summit in December 2022 – which also suffered from a long hiatus, with the first having been held eight years prior.

Keen to express that these delays were some sort of anomaly, at the summit Biden proclaimed that the United States was “all in on Africa.”

Does this visit bear out his proclamation?

To answer that question, it’s worth looking at the commitments Biden made two years ago, such as the pledge to invest $55 billion in Africa over three years. Our internal tracking at Development Reimagined indicates that significant challenges remain in terms of both the volume and direction of financial flows.

In terms of volume, despite some activity, at this stage it looks highly unlikely that the United States can meet the $55 billion commitment. Take U.S. bilateral lending to African countries, for instance. From 2020 to 2022 U.S. debt stocks in Africa rose slightly, from $6.5 billion to $7.1 billion. During this period, the U.S. international Development Finance Corporation (DFC) worked hard to triple its lending to Africa from $600 million to $3.2 billion. However, DFC lending slowed after 2022, falling from $3.2 billion in 2022 to $2 billion in 2023 and $1.2 billion in 2024.

Similarly, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) fairly quickly after the 2022 summit signed compacts with five African countries – starting points for being able to grant or lend those countries money for projects. The MCC also signed the first-ever regional compact for the development of the Niamey-Cotonou transport corridor. A second regional compact was approved in September 2024 and two more are reportedly being developed with Senegal and Cabo Verde (which Biden also visited just before arriving in Angola). Yet, this progress notwithstanding, with a budget of less than $1 billion in 2023, the MCC remains far too small relative to the $55 billion commitment. In any case, the Niamey-Cotonou regional compacts has been put on hold due to political differences following the military coup in Niger.

The picture doesn’t look much different when it comes to the private sector, with foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from the U.S. to Africa slowing in the recent past. The stock of U.S. FDI in Africa between 2020 and 2022 rose by only $2 billion to $46 billion (in the latest available data). And while the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) since the summit has funded at least 10 feasibility studies – half of which were for infrastructure projects in the clean energy, health, and digital infrastructure sectors – in an effort to de-risk and attract private investment, financing for these projects is yet to materialize.

Another U.S. scheme, Prosper Africa, has reportedly facilitated 1,695 deals under the Biden administration, valued at $63.5 billion across 41 African countries. However, because the majority of the deals executed thus far actually predate the second U.S.-Africa Leaders’ Summit, there has been limited new productive investment in Africa under the Biden administration.

If the volumes can’t be met, perhaps transformation can still happen by the United States “going all in” on infrastructure financing – a core priority for African countries. In this respect, the major project that Biden is going to be discussing during his visit to Angola – the Lobito Corridor railway, funded under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI) at a tune of over $1 billion – is really the shining light. However, it is the lone major infrastructure investment project undertaken by the United States in Africa in decades, and it has not been easy.

Of the U.S. financing flows we have tracked, most do not appear to have African priorities as their focus. For instance, from 2021 – 2024, DFC lending in Africa was mostly concentrated in the finance and insurance sector, which accounted for 51.5 percent (around $3.7 billion) of total lending. Out of the three infrastructure-related commitments announced at the U.S.-Africa Leaders’ Summit, only one project involved direct investment by a U.S. company, with the rest being exports of equipment.

U.S. Africa policy is increasingly viewed through the prism of competition with China, which has taken on a more expansive role in Africa in the last two decades. Since launching the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, Chinese companies have invested over $12 billion in Angola alone. In fact, “Chinese FDI flows to Africa have exceeded those from the U.S. since 2013, as U.S. FDI flows have generally been declining since 2010,” according to the China Africa Research Initiative.

Certainly, Biden’s trip to Angola this week is an opportunity for the U.S. president to shape the legacy of the Democratic Party in Africa, as well as spurring African leaders to consider what they want from the second Trump presidency.

While in Angola, Biden is expected to announce some further investments relating to the Lobito corridor. This will be welcome, but to have a larger impact the president should announce interest in other infrastructure projects on the continent, as well as agree to expansion of the Lobito railway to other countries that have shown interest.

This could be backed by two other, broader actions.

First, Biden could make the case for U.S. government authorization of the DFC to take on more big-ticket projects in Africa, especially by providing more early-stage, low cost, and long-term financing to African countries and for priority regional integration projects as enshrined in the African Union’s Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA). Alongside this, Biden could also make the case for expanding the MCC’s resource envelope to enable it take on larger infrastructure projects in transport and logistics, energy and healthcare.

Biden should also use the visit to bring together specific U.S. and African firms that plan to boost Africa’s manufacturing capacity, building on an MOU that was signed between the U.S., DR Congo, and Zambia in 2022 to develop an EV battery regional value chain. It’s a fact that U.S. firms control more assets related to critical minerals in Africa than Chinese firms do – this is the moment for these firms to explore new business models that enable processing and value addition of the minerals on the continent rather than export to China, Europe, or other markets. Making the case for providing guarantees and increasing funding to USTDA for de-risking projects to attract U.S. private investment in areas such as this could be a further next step.

In some ways Biden’s long-awaited visit to Angola spotlights the fact that the Biden administration fell very short of the high expectations it set for itself. That said, going forward, including under the next Trump administration, the solution is not to under promise, nor keep quiet about African demands and visions. African leaders know there is plenty of potential for the United States to really go “all in” on Africa. The first step is to align U.S. commitments with the priorities of African countries, then use the existing tools at its disposal creatively and effectively to follow through.