In 2014 I and roughly 150 others arrived to work for The Center for Teaching and Learning in China (CTLC), a company that since 1996 had brought a new cohort of teachers each year, mostly from the United States, and deployed them across Shenzhen to teach English in public schools. We were almost all recent college graduates with varying degrees of Chinese language and teaching experience, many of us eager to find opportunities to work in the world’s fastest growing economy.

China was in the midst of blistering economic growth and the impressive spectacle of the 2008 Beijing Olympics was fresh in people’s minds. China was seen as the place to be, a country swiftly rising on the world stage. One young British writer went so far as to compare Beijing to Paris in the 1920s.

It felt like we had arrived in a land of opportunity at just the right time to join in the boom. Before our eyes skyscrapers shot up, subway lines expanded at an unprecedented pace, and technology advanced at a speed that seemed to even outrun the Western countries we had all hailed from.

While not everyone in the group intended to embark on a China-related career, most at least arrived with an openness to the exciting opportunities we had all heard of. Everyone was eager to learn and see more. For some, their trip to China was their first outside of their home country. Yet now only a few of that group remain in China, and even fewer outside the country have jobs that make use of Chinese language skills or relate to China in any way.

2014 turned out to be the final year that CTLC hired any new teachers, and what we thought was the beginning of an exciting new era in China was actually the end. What could have been the next generation of bridge builders between the two countries now mostly only remains connected to China though some happy memories and a continued appreciation for Chinese food.

To understand how this came to pass, I spoke with more than a dozen of my former colleagues. A few major themes stood out: the difficulty in navigating cultural and language barriers, lack of opportunities for foreigners outside of teaching English, an increasingly repressive atmosphere, worsening relations with the outside world, and a change in U.S. perceptions of China. For many, COVID-19 disruptions were the final nails in the coffin of their China dreams.

* * *

While members of our cohort arrived in China with varying levels of previous interest in the country, many of us had been studying Chinese since high school, often in the hopes of securing career opportunities. In the years leading up to our arrival, Chinese language enrollment had been on the rise, and parents were eager to get their kids into classes. Even Donald Trump’s granddaughter, Arabella, studied the language and would later famously sing in Chinese.

Brielle O’Brien, currently a human resources professional in New Jersey, started studying Chinese before arriving in China. Her experience is emblematic of many in the program who started learning before college: “They started offering Chinese as a class at my high school when I was a junior and I ended up really liking it… then when I was applying to college I decided to major in Chinese.” While she personally enjoyed learning the language, she mentioned that her study “was definitely career-driven…The main goal for me going over there was to use my Chinese and practice, improve, and get to the point where it could lead me to a career where I could use it.”

Peter Sorrell, now a translation services manager, who started at CTLC two years before I arrived, had a similar experience, “It was hyped up a lot with people I would talk to… [people would say] ‘oh Chinese and business, that’s really smart that you’re studying that, that’s gonna be useful.’”

Our first impressions of China seemed to track with these high expectations of dynamic excitement and opportunity. John Angarola, a teacher from skyscraperless Washington, D.C. marveled at Shenzhen’s glittering towers. Almost everyone I interviewed mentioned being impressed by the scale and sense of progress with rapid construction, clean gleaming subway stations, and more advanced technology every time they returned.

But as time went on the problems and obstacles became more apparent. Chinese was difficult, even for those who had started in high school. The Chinese people we met were friendly but guarded, and closer friendships were hard to forge. Adopting and understanding the local social norms and fitting in as a foreigner could be tricky. English teaching was a way into the country but for many, seemingly a dead end.

Troy King, one of the few to remain in China for the past 10 years, said he “came in with really high expectations with how quickly I would feel out the language… that didn’t happen.” Even those who began in high school expressed frustration. “My language skills plateaued at a certain point,” said O’Brien, “at the end of [two years in China] I still don’t think my Chinese language ability was at the level…for positions that required full fluency.”

Brian Drout, one of the other few remaining in China from the program, found that the challenge of Chinese and adapting culturally was “the experience of [feeling like a] total idiot… the learning curve was very humbling.”

English teaching also wasn’t a position that lent itself toward Chinese fluency. Kirby Imholte noted that “a lot of people were eager to practice their English… it became the default.” When we gathered, our conversations would turn toward what was next for us in China and we often shared the same feeling: “I think the English teacher track is kind of a dead end for a lot of people,” Sorrell expressed. Teaching was a way in, but beyond making slightly more money at a more prestigious teaching position, there didn’t seem to be any way up.

Due to these difficulties and more, the CTLC program had long had a high turnover, with most teachers only lasting a year or two before being replaced by a fresh crop of bright-eyed graduates. However, in 2014, 18 years into the program, that all changed.

A contract signing ceremony for foreign teachers in Shenzhen in 2014, including the final cohort of CTLC teachers. Photo courtesy of Mark Witzke.

* * *

Of course, the difficulty of learning a new language as difficult as Chinese and bridging cultural differences were to be expected, but things were changing in China in ways that we had not anticipated. Unlike previous generations of those going to China, teaching companies would soon face new difficulties in recruiting teachers. As I and the rest of my cohort planned for a second year, we learned that new regulations meant that foreign teachers in China would face higher scrutiny and much higher requirements.

Meanwhile, the anti-corruption campaign led by Xi Jinping had begun to reach new heights and the company’s connections to the Shenzhen bureau of education were adversely affected. Julian Wheatley, head of the language program at CTLC, noted, “We were so well integrated in Chinese society that even we were forced out by the anti-corruption campaign.” Due to the company’s tight integration with local bureaucrats facing investigations and much more scrutiny with new regulations, our 2014 cohort was the final one for the company. A pipeline of over 100 English teachers to Shenzhen each year was severed permanently.

Beyond these new guidelines for foreign teachers and the shutdown of any new teachers from our company, we all started to notice a generally more stifling environment. I remember clearly the day in 2014, a few months into my time in China, when Instagram was finally completely blocked, to my high school students’ resigned disappointment. We foreign teachers had been warned that we would need VPNs, but over time, they became trickier to access and connections were spottier. The physical distance between China and our homelands was vast, and the solidifying digital divide made it feel even larger.

The restrictions piled up, and we all grumbled over our long visits to the proper administrative buildings, the long police lectures, and the additional rounds of paperwork. We all knew other foreigners who worked more surreptitiously on tourist visas and had to go back to Hong Kong for visa runs once a month but we, the ones trying to follow all the rules, were the ones who seemed to be punished for it.

Kirby Imholte, who after a few years with CTLC had risen to be the national coordinator of the program, said that beginning in 2014, China started to feel “a little less welcoming for foreigners… our last year there they got a little bit stricter with visas.” Incredibly, even the well-vetted national coordinator faced near weekly apartment visits from authorities with demands to see her passport and proper paperwork.

With no more new arrivals, CTLC would limp along in a diminished capacity with its rapidly shrinking cohort of existing teachers until it shut down completely a few years later. The original company website, chinaprogam.org, once one of the top Google results for “teaching in China,” now inexplicably redirects to a website for a hair removal clinic in Osaka, Japan.

Many members of my cohort chose to stick it out for a second year without any new teachers, but each year after that the drop-off was much sharper. Eventually the obstacles became too much. Families wondered when we were coming back, and a future in China started to seem dimmer.

Even those who were the most resolute in their Chinese study and amenable to teaching English were starting to be worn down by the atmosphere. Angarola had completed an intensive Chinese study program and later continued to teach in the United States, but he began to be more worried and cautious in mainland China. Things “got stricter even over the years that we were there and seeing how that trajectory was continuing… it didn’t seem like a place I could feel fully settled in,” he said. Angarola chose to go to Taiwan after two years.

Those who stayed made progress in their careers, but even the ones who reached a high level of language proficiency had trouble fitting in. Antonio Jackson, an African American, earned a master’s degree in international relations at Xiamen University after a few years with CTLC. “Chinese people are not used to foreigners being able to speak their language, especially ones that look like me,” he told me. “They were always shocked… which at first I thought maybe was kind of flattering, but after a while it was like, yeah people can speak your language, it’s not rocket science.”

After Xiamen, Jackson went on to get a job at China Central Television (CCTV) in Beijing, arriving there in 2017. He said that it was a good experience living in Beijing but noted that at CCTV, “They keep their foreign coworkers at arms length… the work culture was very rigid and hierarchical.” He said that “during the trade war with the U.S.…I felt like that’s when sentiments kind of took a turn for the worse… it just started to feel a little tense.”

He left China for good in 2019, feeling worn out and disillusioned. Speaking to me in 2024, he said that when he left he thought, “maybe in five years I would go back [but] it’s been five years and I think I could do another five” before returning to China.

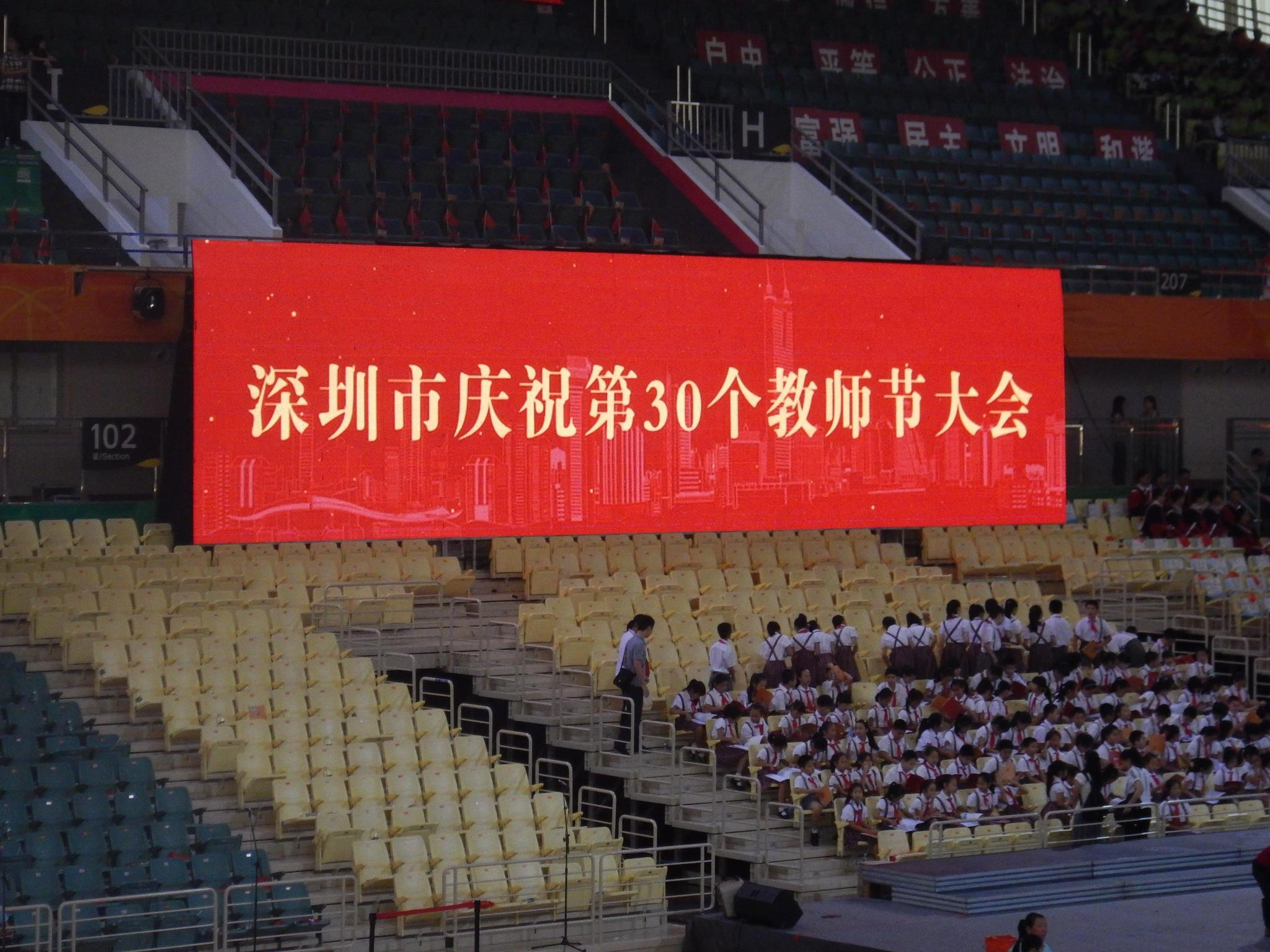

A ceremony celebrating Teacher’s Day, September 10, in Shenzhen, China, 2015. Photo courtesy of Mark Witzke.

* * *

While we chafed at growing restrictions in China and continued into our second year, something was happening in the United States. The 2016 presidential election had two candidates who were both decidedly more hawkish on China than previous administrations. The eventual winner, Donald Trump, was eager to start an “easy to win” trade war. His victory coincided with a growing policymaker consensus of distrust toward China.

China was lambasted for stealing U.S. jobs and hollowing out its industrial base. Fears of China acquiring influence and technology in the United States drove new restrictions on Chinese investment. China’s arrival on the world stage saw it embroiled in more frequent and intense international controversies in the South China Sea, with Japan, and along its borders. The rise of China began to be seen as more of a threat to be managed than an opportunity to be taken advantage of.

The increasingly authoritarian turn at the very top of Chinese politics as Xi Jinping removed term limits on the presidency in 2018 heightened these fears of China’s rapidly growing strength. As the tide shifted, public opinion followed and China’s favorability in the United States – which had inched up slowly from a nadir after the Tiananmen Square massacre to just past 50 percent in 2018 – again plummeted to unseen lows. Chinese language course enrollment and foreign students studying in China started to fall from their peak around 2016.

Those of us who returned to the United States collided with these shifting views on China. When we left, we were hailed as making a good move for our future; on our return many of us were met with skepticism. Nick Giorgio, now a teacher in Mississippi, tried his “best to change people’s perceptions because there were a lot of stereotypes out there.” Most had to scramble to adjust their career stories and de-emphasize their time in China. Jackson noted that when employers looked at his resume, “what [I thought would be] an advantage was actually a detriment.”

Some found work for a year or two at jobs related to managing Chinese translation projects or consulting for Chinese students who wanted to attend U.S. colleges but mostly drifted away from anything to do with China or Chinese specifically. Megan McLoughlin, now in business development unrelated to China, pointedly said, “I definitely did not think years of learning Chinese would result in just being a fun party trick.”

Others complained that for government or other sensitive work, their time in China was seen as a potential hazard. Security clearances were especially difficult for those who had spent several years in China with a now defunct company. One former teacher remarked that “my entire shot at making it to [my current company] was held up because we could not prove I lived in China in the way that they needed.” At a time when the United States seemingly needed China expertise more than ever, those who could have made a difference were being turned away or faced extra obstacles.

* * *

By 2019 only a handful of my CTLC cohort remained in China. They were impressed by the massive changes and progress they had seen over their five years but felt that things had started to stagnate. By then, rising international tensions and a slowing and more unequal economy had dampened enthusiasm from Chinese and foreigners alike.

Despite all this, some tried to persevere or return, but there was one last storm on the horizon: COVID-19. O’Brien said that in 2020 she was “slated to lead a school trip to Taiwan but it was canceled due to COVID… I thought I was gonna get back into Chinese and learn again and now I haven’t used Chinese in so long that it feels like I’m just losing it completely.”

As the pandemic roiled the world, several of the remainders fled China or struggled through intense lockdowns. Troy King, still a teacher in Shenzhen, was the only one I interviewed who was in mainland China for the entirety of the pandemic. He said that the pandemic was the only time he felt discriminated against in China as Chinese people would see him and immediately put on a mask or all shuffle away from him on the subway.

A few years removed from their time in China and watching China navigate strict lockdowns, some viewed themselves as leaving at just the right time. Sorrell said that with “the draconian way they handled COVID, I feel a bit vindicated that I wasn’t gonna be involved in China anymore.” Others noted the shift from sunnier relations between the United States and China, the crackdown on Hong Kong protests, growing anti-foreign sentiment, and consolidating authoritarianism as reasons that made China a less attractive place than they originally thought.

While these are just the stories of one company, you could hear similar reflections from thousands of other students, teachers, academics, and entrepreneurs who went to China during this period. The implications for China-U.S. relations are grim. As foreigners and foreign investment in China fall to the lowest levels in decades there has been a huge missed opportunity from both the U.S. and China to create the next generation of connective tissue between the world’s two most important and powerful nations, something that creates greater risks of conflict, lowers mutual understanding, and misses out on the chances for economic growth and development for both countries.

Those who tried the hardest to understand are viewed with suspicion and distrust. What could have been an era of increased cross-border investment, talent flows, R&D collaboration, fair tech competition, tourism dollars, and increased trade has instead been for years an escalating tit-for-tat cascade of new restrictions. Tariffs, investment screening policies, restrictions on data flows, hostage diplomacy, race-fueled paranoia, shuttered consulates, and diplomatic boycotts have not brought the two sides closer to any fruitful resolution.

The next generation of Americans – those who consider focusing on China today – face an entirely different environment than we faced 10 years ago. The Great Firewall stands taller than ever, arbitrary detentions of foreign nationals are a threat, and the opportunities of being in China are fewer than they once were. The U.S. State Department travel advisory only recently changed from “reconsider travel” – the second strongest caution before “do not travel” – to “exercise increased caution.” That designation gives many study abroad programs and foreign workers pause. In the United States, too much time in China can also be seen as a reason for suspicion of being too sympathetic to a “systemic rival.”

* * *

But there are still a few who have hope for the future. While most have ventured into different careers and life paths, almost all those interviewed remembered their time in China with fondness and said they would be eager to travel there again if given the chance now that COVID-19 restrictions have receded and China is loosening visa restrictions.

A few also remain in China. King is one of those who made it work. Still in Shenzhen, he is now married to a Chinese national and has a 2-year-old. “The reason why anybody did stay is they had a very compelling reason to be here, whether that be a significant relationship or a career path…” he mused. “In China there’s a lot of highs and a lot of lows… if you have something compelling it does shift your sights to the good parts of living [in China].”

Brian Drout arrived in 2014 and after one year in CTLC moved to Nanjing, then to Beijing for a master’s degree as a part of the Schwarzman Scholars program. He said after a year away in London, “standing at the crossroads again… China actually felt like a place of comfort.” Drout returned and joined “The Hutong,” a company that provides study abroad trips and other cultural programs. He has split time between Beijing and Hong Kong since 2019.

Reflecting on the China-U.S. relationship after 10 years of living mostly in China, he said, “because the relationship is strained, it’s even more important to go and have that understanding… bring a critical eye but go with an open mind.”