Late last year, when several thousand Okinawans protested the sexual assault of a 16-year-old girl by an American soldier stationed in their island prefecture, the People’s Daily, a major Chinese state media outlet, spun the story. Okinawans, it reported, were demanding a complete revision of the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement, the rules that govern U.S. military bases in Japan.

What the newspaper neglected to tell its readers was that the changes sought by the protesters were aimed specifically at preventing sexual assaults. Indeed, the crime that sparked the protests was given only a token mention, leaving the impression that it was the Japan-U.S. alliance itself that Okinawans opposed.

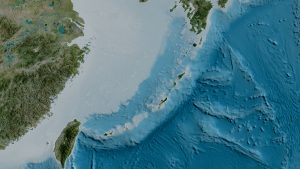

Okinawa bears a disproportionate burden for the alliance, with 70 percent of U.S. bases in Japan located on the islands. That makes the prefecture both strategically important and vulnerable. China’s goal is to drive a wedge between Okinawa and mainland Japan, in order to destabilize the Japan-U.S. alliance and weaken Japan’s security posture.

The internet is a powerful tool in that effort. Anti-U.S. and anti-Japanese narratives created by Chinese media and trolls incite opposition to the U.S. military presence. Some even go as far as to agitate for Okinawa’s independence from Japan. These narratives are published in multiple languages, with Chinese versions designed to incite Chinese netizens to spread the word further. Some claim, contrary to all historical evidence, that Okinawa used to be a part of China. The concern is that China might one day claim Okinawa as its territory.

Over the past year, alarmed Japanese media outlets have expanded their coverage of Chinese disinformation about Okinawa, exposing some of these false narratives. Nikkei and Asahi, two major newspapers, have uncovered disinformation from China that exaggerates pro-independence sentiment.

Outright lies are not the biggest problem, at least when it comes to influencing public opinion in Japan. In part because Japan is less politically polarized than many other countries, notably the United States, fewer Japanese internet users tend to respond to and repost outright disinformation. Strong public sentiment against China also acts as a firewall: people don’t trust disinformation that can be easily associated with the Chinese government.

What is more alarming is the subtle manipulation of facts – a phenomenon that experts call malinformation. There is a lesson to be learned from Russian influence operations over Ukraine. Outright lies gained little traction – few people, for example, believed the Russian fabrication that the United States had built biological and chemical weapons factories in Ukraine and used their output against Ukrainians. But malinformation was more effective. For several months after the invasion began, many Japanese media parroted the Russian propaganda narrative that NATO’s eastward expansion was the cause of Vladimir Putin’s aggression against Ukraine. In reality, there was no prospect of Ukraine joining NATO at the time of the invasion. This was simply malinformation created to manipulate international public opinion – using the real history of NATO expansion to draw a false parallel.

It was problematic that the Japanese media took this perspective because it gave a sense of legitimacy, albeit limited, to Russia’s aggression. It turned some people into de facto apologists for Russia, in the name of taking a “neutral view” of Putin’s actions.

China has made extensive use of malinformation. Its story about the Okinawa protests – headlined “Okinawan People Demand Review of U.S.-Japan Status of Forces Agreement” – reported real events in a selective way to portray a faltering Japan-U.S. alliance. This was not disinformation per se, but was typical malinformation.

Awareness of disinformation in general has been increasing in Japan. The media regularly reports on lies and hoaxes found on the internet. The government has established a structure to counter disinformation by external actors, with the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense collecting information, the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office conducting analysis, and the Cabinet Secretariat stepping up public communication to counter disinformation. The government has also strengthened cooperation with partners such as the U.S., South Korea, and the EU to tackle the problem.

What is missing, however, is programs to fight malinformation. Malformation is difficult to tackle through fact-checking and debunking, so deeper research is required to identify it and to answer important questions, like what groups is it targeting and why? Fighting back requires counter-narratives – compelling true stories that can unite Japanese society in the face of authoritarian propaganda and strengthen the values of democracy and human rights that are often targeted by malformation.

This requires a whole-of-society approach. Government agencies might be able to identify the source of foreign influence operations, but they’re not adept at creating emotional stories that shape social values and norms. This is especially true of the Japanese government.

Instead, it is the media and NGOs that are good at creating impactful narratives. As independent actors, they can provide genuine voices that resonate with society. While the government should avoid working so closely with such private actors that they get labeled propaganda tools, it can foster an environment in which private actors willing to disseminate pro-democracy messages can flourish. Providing grants for NGOs that create narratives to protect society is one possible option. Helping connect such actors with leading international voices might be another.

Compared with blatant disinformation, malformation is complicated and hard to tackle, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. That is especially true when it comes to important and potentially vulnerable targets like Okinawa. It is time to strengthen countermeasures to protect Okinawa from China’s influence operations, the Japan-U.S. alliance from fragility, and Japanese society from polarization.