China seemed to take the air out of the Geneva Accord on Iran with its simultaneous announcement last week that it is creating an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea. The ADIZ will be implemented by the Chinese Ministry of Defence and obliges all aircraft flying in the zone to accommodate a number of rules including: the identification of flight plans, the presence of any transponders and two-way radio communication with Chinese authorities. Predictably, the move was strongly condemned by both Tokyo and Washington and escalates the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands row to an even more dangerous level. This development also signals Beijing’s indifference to the continued descent of Sino-Japanese relations as well as a closed-fisted challenge to Washington’s rebalancing to Asia. Calibrating a firm and united response to this is a crucial test for the U.S.-Japan alliance. The U.S. has already signalled its displeasure with a B-52 flight across the disputed islands.

Yet, while the bullish move is predominantly a shot across the bow to both Tokyo and Washington, there are other interesting layers of the ADIZ, which may produce negative externalities for China’s other relationships in the region. For example, the imposition on the ADIZ has likely reinforced for several Southeast Asian states – Vietnam and the Philippines in particular – the image of Beijing as bent on throwing its weight around to achieve a desired end state on its maritime disputes in the South China Sea. The action has also further cooled once budding ties between China and Australia. Canberra summoned China’s ambassador to Australia this week and released a statement blasting the ADIZ as “unhelpful to regional security.” And the ADIZ, which also covers Taiwan’s airspace, has widened the cross-Strait rift with Taipei – a tussle that became more knotted following Japan’s fisheries agreement with Taiwan in the East China Sea earlier this year.

But there is fallout from the ADIZ that has the potential to be particularly harmful to China’s interests. In an apparent blunder, Beijing stretched its ADIZ boundaries to include South Korean airspace. Specifically, this zone covers a submerged rock in the East China Sea named Ieodo and parts of airspace surrounding Jeju Island. While Ieodo is not allowed, under the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, to be claimed as territory by either state due its status as a submerged rock, both Seoul and Beijing argue that the reef falls under their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The reaction from Korea to the ADIZ announcement has been bristling. Seoul reportedly summoned a minister from the Chinese Embassy in Korea to denounce the unilateral ADIZ and has warned Beijing that it will not comply with these rules. In fact the Ministry of Defense in Korea released a statement earlier this week stressing that it “will fly aircraft over Ieodo as usual without informing China.” Korea maintains an ocean research center on Ieodo and has insisted that it is determined to defend its claimed EEZ. China for its part has been backpedalling quickly to mitigate the diplomatic fallout with Seoul, indicating that the intention of the zone is not to box Korea in on Ieodo. The row is further complicated by the fact that Japan also has an ADIZ over Ieodo, but one that is largely benign due to the fact that it does not require Korea to identify aircraft.

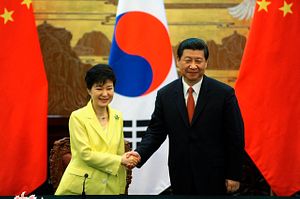

The ADIZ dispute between Korea and China comes amid a mini-honeymoon in bilateral ties. Korean President Park Geun-hye made a landmark four-day trip to China this past June and seemed to be at ease with Xi Jinping. Park appeared willing to quarantine historical differences over North Korea and instead focus on enhancing economic relations with Beijing. This included kick-starting long awaited bilateral free trade talks as a complement to trilateral talks with Japan. And Seoul and Beijing have appeared in lockstep with their harsh condemnation and censure of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s statements on historical issues. Indeed, China has reveled in the widening rift between Tokyo and Seoul and secured a diplomatic coup when Park made an unprecedented snub of visiting China while ignoring Japan’s call for a summit with Abe.

Korea’s disenchantment with Japan has become so pervasive that it has prompted Washington to get involved in an attempt at mending fences. Yet calls for a patching up of ties have thus far fallen on deaf ears in Seoul, and Park recently dressed down Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel when he suggested that South Korea needs to cooperate with Japan on pressing security issues such as North Korea. Park also reportedly dismissed U.S. President Barack Obama’s call for stronger trilateral cooperation on Pyongyang, opting instead to prompt him on the need for trilateral cooperation with China. A fractured trilateral relationship has been a long-held goal for China, which aims to defang the U.S. alliance structure in East Asia – a system that protects against Chinese regional hegemony. This has also flustered U.S. attempts to reassure Japan and Korea on its extended deterrence commitments, as both sides have different threat perceptions and some are even interlinked, in the case of Seoul’s unease with Japan’s defense reforms.

But now, five months after the Park-Xi summit, it seems that relations between China and South Korea may be creeping back to their normal state: opportunity coupled with mistrust. The ADIZ flap has the potential to exacerbate other simmering coals in the China-Korea relationship, such as their dispute over Baekdu Mountain or concerns over cyber security. While both sides will look to mitigate this disagreement, the ADIZ still elevates the potential for a miscalculation that would effectively erase the goodwill from the June summit. Meanwhile, there are other variables that are outside Seoul and Beijing’s control, such as a provocative action by North Korea aimed at leveraging a break in consensus between the two. Finally, while bilateral ties with Japan will remain cool, this action may ironically resuscitate the languishing trilateral relationship with Tokyo and Washington, simply out of necessity.