Five years ago, foreigners walking down Rudaki Avenue, Dushanbe’s main drag, could expect to be greeted by a steady chorus of “hellos” and “privets” from knots of neatly-pressed students. But now, they’re just as likely to hear “ni hao.” As China makes deeper inroads into Tajikistan, students of all ages are increasingly choosing Chinese language courses to supplement their education.

In the past 20 years , the number of students enrolled in Chinese courses at the Russian Tajik (Slavonic) University, one of the top universities in the country, has grown by a factor of 10, from 20 students in 1997 to almost 200 today, according to administrators at RTSU’s Linguistics Faculty. And while there are no Chinese classes offered in Tajik primary and secondary schools, the Confucius Institute at the Tajik National University in Dushanbe, founded in 2009 and supported in part by the Chinese government, enrolls students as young as nine in a regimen of thrice-weekly classes.

Jomi Emomov, a first-year student at Tajik National University, said that even in the six months he’s studied at the Confucius Institute, the number of students taking Chinese courses there has grown considerably. A new Confucius Institute branch opened in 2015 at a mining college in the northern city of Chkalovsk.

The Confucius Institute also offers students opportunities for scholarships to study in China, including a program for high school students similar to the U.S. Embassy’s grants for study in America. Most students here head for Urumqi, the capital of China’s Xinjiang province, giving rise to jokes about the “Tajik university” in that city. Plenty also make for Beijing.

“When I arrived in Beijing, I was one of maybe 60 or 70 Tajik students in the city,” said local entrepreneur Iskandar Ikrami, who studied in Beijing. “When I left in 2010, there were well over 400.” He adds that “it’s easier now for people to study in Beijing,” because rising middle-class incomes in Tajikistan mean more families can afford the roughly $2,000 per semester for room, board, and tuition.

But schools seeking to attract students to Chinese language courses face stiff competition in Tajikistan. Even as the quality of and access to Russian language instruction has declined considerably since independence, students still overwhelmingly choose to study English and Russian rather than Chinese.

Students enrolled in Chinese language courses say that their priority is first Russian, then English, and then, if they’re able, Chinese. Komron Dustov, an employee of MBO Professional, a private language learning center, said that among his company’s seven locations around Dushanbe, there are barely 15 students studying Chinese. They’ve had to shut down Chinese language classes due to lack of demand.

“Students would just rather learn English,” he said.

Where once students were attracted to the study of Chinese by the promise of lucrative jobs as translators and fixers for Chinese firms in Tajikistan, high-achieving students now see adding the language to a repertoire of Tajik, English, and Russian as just common sense.

A decade ago, when China was first expanding cooperation with Tajikistan, Tajik fixers at Chinese ventures here could expect a cut of the profits in addition to a salary, leading to big payoffs, said Ikrami, who himself worked as a fixer and interpreter. But as China’s cooperation with Tajikistan has normalized, that lucrative practice has ended. Now Tajik fixers for Chinese firms earn wages on par with their English-speaking counterparts – between $400 and $700 a month for entry-level logistics positions.

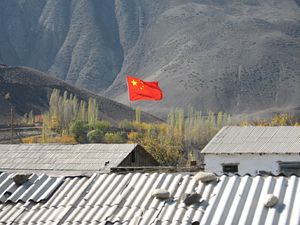

China invested $273 million in Tajikistan in 2015 – representing a 160 percent increase over 2014 Chinese investment, and vastly outstripping other sources of foreign investment. The two countries are also deepening military cooperation. In 2016, Dushanbe gave Beijing the green light to build 11 new border checkpoints and a new military facility on the Tajik-Afghan border. The same year, over 10,000 Chinese and Tajik troops participated in joint counterterrorism and counter-narcotics exercises in southeastern Tajikistan. Beijing’s efforts to ensure stability in southern Tajikistan are likely tied to protecting its investments in the lauded “One Belt, One Road” initiative, of which Tajikistan lies on the southern border.

In Tajikistan, Chinese infrastructure development has advanced in fits in starts. A new network of smooth, well-maintained roads carry the most noticeable Chinese stamp, with Chinese characters prominently displayed on tollbooths and tunnels.

China may become the biggest investor in the Rogun hydropower plant, a geopolitical boondoggle upon which Tajik President Emomali Rahmon has pinned his reputation. If ever completed, the Rogun plant would be the tallest hydropower plant in the world and generate enough power to end Tajikistan’s electricity rationing for good, and turn the country into a net exporter of energy. Completing Rogun is expected to cost around $4 billion, and as of yet, it’s not quite clear where that money will come from.

China has signed on to build Saihoon, billed as Tajikistan’s “first new city since the country’s independence.” But locals and foreign observers alike are left scratching their heads over the city’s proposed location, in the middle of an arid region without a ready supply of water.

Given the boom in urban development across Tajikistan, carried out in large part by Chinese contractors, Saihoon’s hype as the “first new city” seems disingenuous. Dushanbe has lately been colonized by shoddily-built prefab high-rises, which Tajik political analysts speculate are funded by sweetheart loans from Tajikistan’s failing banks. It’s likely a large chunk of that grey money ends up in the pockets of Chinese construction companies operating here.

Meanwhile, tensions between Tajiks and the recent influx of Chinese money and citizens are broiling over Chinese farmers’ occupation of land in southern Tajikistan, pollution from Chinese-backed cement plants, and China’s annexation of Tajik territory in 2011 in exchange for debt relief. And rumors abound that China has its eye on another parcel of Tajik territory – this one in southwestern Tajikistan, far from the Tajik-Chinese border. The land, close to Rahmon’s hometown, possesses sizable precious metals deposits.

But Tajik students of Chinese language – at least in Dushanbe – don’t seem overly concerned about the fraught politics. On a rainy day at the Confucius Institute, they giggled over their attempts at brush calligraphy, pored over their character charts, and ogled a Chinese soap opera.

“I study Chinese because it’s clear China is a great power,” Emomov said simply – but he’s also hedging his bets with English, Russian, and Arabic.

Katherine Long is an American Fulbright student researcher in Tajikistan who been published in Roads and Kingdoms, Mashallah News, and the Guardian.