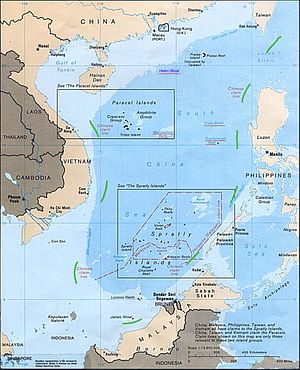

In 2012, China began administering the Scarborough Shoal, challenging the Philippines’ claim to the area. In 2013, China imposed an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over disputed waters in the East China Sea. In 2014, China asserted its claim to the Paracel Islands by stationing an oil rig a few miles off their shores, in Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

As a result of these and other actions, China is now widely perceived as a regional bully. Instead of using any sort of positive legal reasoning (or, occasionally, using heterodox reasoning) to justify its territorial claims, Chinese state representatives tautologically reference historical documents and precedents as the proof of the righteousness of their claims — everything else becomes a “rumor” or a “myth.” We saw this exhibited most recently with the rhetoric of Chinese representatives, from both the PLA and the National People’s Congress, at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. When it comes to enforcing claims, assertive tactics seem to be working for China, but, as my colleague Shannon wrote earlier today on our China Power blog, those same tactics earn China few friends in the region.

The only thing better than winning in international politics is winning with honor, prestige and influence; despite current trends, it is not too late for China to salvage some positive reputational capital out of its handling of its disputes in the East and South China Sea. There are good reasons for China to do so as well. As Xi Jinping exhibited at the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) recently, China has ambitions for normative leadership in Asia. Shortly after CICA, the Shangri-La Dialogue exposed the massive rift between China and other Asian nations when it comes to values. In short, China and the rest of the Asian rimland have a very different read on the security status quo and on who they believe should lead it in the future.

China can take steps to bring about its vision of the future Asian order. One example that Shannon briefly mentioned is that China could take steps to resolve its disputes diplomatically with Brunei and Malaysia in the South China Sea. While these countries do have territorial disputes with China, neither treats Beijing as an urgent threat as the Philippines and Vietnam do. Since China took the Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines, its actions in its near seas demonstrate a conviction that it believes that it cannot gain the acquiescence of Southeast Asian countries or Japan to its territorial claims without explicitly administering these areas. Should China engage in productive diplomacy — even without winning an immediately favorable resolution — it could lessen the extent to which it is perceived as a threat across the region.

While normative influence isn’t explicitly or necessarily a consequence of soft power, it certainly cannot be won through coercion. American hegemony came about after victory but only because the United States was able to align itself with the values of those powers across the Atlantic that came to become major partners in the aftermath of the Second World War. Granted, the existence of the Soviet Union did offer a formidable alternative to America’s normative vision. In the end, the contemporary liberal international order was forged with significant American influence. If China wants to lead the way towards an “Asia for Asians,” with limited U.S. influence, it must invest in cordial multilateralism. The ease with which Chinese delegates at the Shangri-La Dialogue, for instance, openly accused Vietnam and the Philippines of mendacity reflects a lack of interest in pursuing the Chinese interest with reason and restraint. It is possible for China to pursue her interests without the sort of brazen provocations that have now become the norm.

If current trends continue in East Asia’s inner seas, China will find itself a victor but only trivially so. It may succeed in bringing about a state of affairs in the next decade where it has successfully enforced its nine-dash line claim to the South China Sea through years of slow-but-sure “salami slicing” only to find itself encircled by some sort of informal or formal Asian entente determined to safeguard what remains of the millennial international order. China’s current behavior is slowly turning its claims of encirclement into a self-fulfilling prophecy. I should add that I fully suspect that China’s leaders are aware of this. They have likely conducted a cost-benefit analysis, weighing the benefits of assertive policing of disputed waters as greater than the normative costs of this policy.

China has more control over security outcomes in the Asia-Pacific than its current behavior would suggest. The sooner China’s leaders recognize this and pursue their national interest in a less acerbic manner, the more likely they will be to enjoy the sort of Asia that Xi Jinping outlined at CICA. This imperative will only grow with time as China’s relative economic clout shrinks relative to the rest of Asia. It isn’t too late for Beijing to win with honor in Asia.