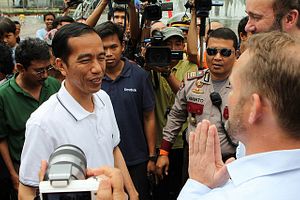

Despite the fact that he still faces a stiff challenge to his victory from rival candidate Prabowo Subianto, Indonesian president-elect Joko Widodo has begun to make sweeping foreign policy statements, suggesting the direction his government is likely to take in seeking investments and alliances. Two interviews he gave with Japanese news outlets this week show an eagerness to partner with Japan in investment, but also shows Indonesia’s neighbors in Southeast Asia which direction Joko could take on territorial issues and regional security in general. He was careful to portray Indonesia as an international arbiter, and thus seemingly above the fray of regional disputes. Should Joko become president in October, following such a narrow diplomatic path in the South China Sea will be difficult. However, choosing a significant ally from outside the region to help balance against China would help to give Indonesia’s position additional weight.

A large portion of the interviews Joko gave to the Asahi Shimbun and Kyodo News were focused on his interest in attracting new Japanese investment to Indonesia. Speaking in Jakarta, he told Kyodo News that Japan was his country’s oldest partner, with bilateral trade reaching $46 billion. Joko spoke with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shortly after Indonesia’s presidential election results were announced, saying he intended to visit Japan soon and that “Indonesia needs investments in the fields of infrastructure, energy and industrialization.” In his interview with the Asahi Shimbun, Joko also said “Japan has been an important partner for more than 50 years. I hope that the (bilateral) relations will become closer.”

Infrastructure is a main target for future investment according to Joko, who despite anti-foreign investment statements during his campaign has said that country’s investment climate now should be “more conducive for the private sector to channel more investment into infrastructure.” Specifically, he is looking for maritime investment to improve island connectivity and deep sea ports, as well as double-track railways. Partnering with Japan is in line with Indonesia’s investment strategy of moving away from extractive industries into sectors higher up the production chain, as Japan’s consumer-based companies have already begun shifting large portions of their production overseas to Southeast Asia. Likewise, Japan has a significant maritime and port facility industry, and its construction companies have a reputation for building resilient infrastructure projects able to withstand substantial earthquakes, which both countries are prone to.

Joko did not mention seeking any larger security or strategic alliance with Japan. When asked, he said “It is important to make bilateral cooperation to build peace and prosperity,” and that “from now on, we will examine concrete measures for cooperation.” When asked about the Japanese Cabinet’s new interpretation of collective self-defense, he responded by saying “I don’t know, but for me soft diplomacy is more important.”

Indeed, Indonesia’s new role as a diplomatic force in Southeast Asia was also a primary topic during the interviews. In reference to Vietnam and the Philippines’ ongoing territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea, “Solutions through diplomacy are desirable. If necessary, Indonesia (which is not part of the disputes) is prepared to serve as an intermediary… [and that] we reject solutions through military power.” Joko also said he would take part in speedily helping ASEAN and China draft a code of conduct in order to help parties settle territorial disputes. Joko’s foreign policy statements reflect the geographical position that Indonesia enjoys, which allows it more strategic depth. Additionally, seeking an outside partner to balance against China could give its policy greater influence.

It is easy to speculate why Joko took this opportunity, before he is even legally assured the presidency by the Constitutional Court, to begin laying out his economic and foreign policy strategy. There does appear to be a message of sorts to Indonesia’s Southeast Asian neighbors. Joko’s emphasis on diplomatic above military solutions shows that Indonesia intends to give itself space to maneuver, and even step back if need be, should the territorial disputes deteriorate significantly.

However, choosing Japan as a primary economic ally does not happen in a bubble. Japan has put itself on a much more antagonistic trajectory with China over the past two years in regard to their dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Additionally, Japan’s reinterpretation of its right to self-defense and its new ability to export military hardware means it is becoming a more active participant in regional security. Indeed, Tokyo has been seeking stronger security ties and military deals in the region with countries like Australia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Mentioning stronger ties with Japan while at the same time asserting a more proactive role in regional affairs could be a sign of solidarity with Indonesia’s neighbors in the South China Sea. It is also a way to underscore Jakarta’s attempt to become a regional leader. Without a robust naval capability of its own, Indonesia requires a significant partner in the region to augment its latent economic and demographic potential. Japan has shown recently that it is also looking to make similar partnerships in the region, as the majority of its energy imports travel through these disputed areas. Even though Joko did not mention a possible security tie-up, China has also likely received the message.