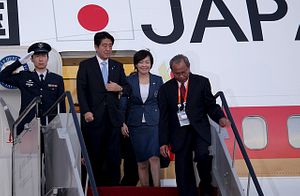

With his recent trip to South Asia, Shinzo Abe has officially upped the tally of the countries he has visited as Japan’s prime minister to 49. All this in the 20-some months he has been in power. That amounts to just over a quarter of all U.N. member states, with an average of over two foreign trips a month. It also, by far, makes him the most well-traveled Japanese prime minister. For comparison, his two Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) predecessors, Yoshihiko Noda and Naoto Kan, visited 18 countries between them in over two years. The enthusiasm with which Abe has been engaging world leaders speaks to his plans for Japan. When he returned to power in late 2012 with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in tow, Abe’s pitch was that he would return Japan to its rightful place as a highly visible economic powerhouse on the world stage. This was after Japan ceded its position as the world’s second largest economy to China in 2011 and was reeling from the seemingly cataclysmic fallout of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and the accompanying nuclear disaster.

In an piece from early August, when Abe’s total stood at 47 countries visited, the Washington Post speculated that Abe may personally just like to be overseas, engaging with various foreign leaders — esepcially amid lower approval ratings at home following April’s sales tax hike and his administration’s reinterpretation of the constitution allowing for collective self-defense. This theory makes sense to a certain extent. Japan’s effusive affair with Abe and “Abenomics” proved to short-lived. While Abe’s domestic situation is far from decrepit, he grows concerned about his political future (as the recent cabinet reshuffle demonstrates).

However, despite slumping approval ratings at home, Abe’s diplomacy has a clear purpose and is driven by three motivating factors: seeking out partners to hedge against a rising China that wants little to do diplomatically with Japan, bolstering Japan’s economy through defense, energy, and commercial deals, and gaining the support of foreign leaders for Japan’s new defense posture.

The first of these is rather obvious, especially under Shinzo Abe, a well-known right-wing nationalist who is particularly poorly received in China. With his overtures to India, Australia, and ASEAN states, Abe has pitched Japan as a relevant counterweight to an increasingly assertive Beijing. While none of these states will leave China in the cold for Japan, Abe has nonetheless managed to forge closer relations with several states across Asia. Back in first term as prime minister, Abe demonstrated his interest in forging a quadrilateral initiative with Japan, India, Australia, and the United States as the four pegs of an Asian security order designed to uphold the status quo. While that initiative failed, his current diplomatic dynamism attempts to essentially achieve the same outcomes through fast and furious bilateralism.

The second factor driving Abe’s trips abroad is pure and simple economics, which long used to be Japan’s foreign policy bread-and-butter. Some scholars had described Japan’s post-1945 foreign policy as an example of mercantile realism. With no real hard power at its disposal, Japan used overseas development assistance, trade and investment deals, and general commercial linkages to forge partnerships across the world. While that remains true in 2014 (see Abe’s recent trips to Bangladesh and Sri Lanka as cases in point), Abe has also expanded Japan’s economic portfolio to include defense deals after the country effectively reversed its self-imposed ban on weapons exports. Since Abe has come to power, Japan has signed defense deals and cooperation agreements with France, the U.K., and Vietnam, with deals with India and Australia in the works. Additionally, Abe has welcomed the involvement of Japan’s private sector when it comes to his travels. On his trips this summer to Latin America and South Asia, Abe brought with him a small army of Japanese executives.

The third factor — gaining support for Japan across the world — has perhaps been the least appreciated among most analysts. Abe makes no secret of his desire to have Japan behave as a “proactively pacifist”Asian state. With an expanded defense budget, a new national security strategy, and a reinterpretation of the collective self-defense clause in the constitution, Abe has put actions behind his words. In an effort to stave off Chinese criticism that Japanese militarism is resurgent and destabilizing, Abe has made a special effort to have almost each and every foreign leader he meets with issue a statement to the effect of welcoming a more active Japanese security role in Asia. Receiving this sort of verbal approval helps tip the scales in favor of Japan. Against all of Beijing’s concerns, Abe is able to point to a long line of leaders both inside and outside Asia that welcome a more active Japanese role in Asian security.

Overall, Abe’s jet-setting will pay important economic and political dividends for Japan. In the face of a China that is rapidly “going global,” Japan can do worse than to have a prime minister affected by a deep sense of diplomatic wanderlust. For Abe, it appears that merely declaring “Japan is back” was unsatisfactory — he wants to deliver that message in person to as many world leaders as he can.