Through the waiting area, past the main desk, and up the stairs, the SEFAM office (on Waris Road, in Lahore, Pakistan) is in full swing. It’s a huge floor with endless rows of desks. Amidst rolls of fabric in various patterns and hues, young designers are hard at work on their computers. The atmosphere at Pakistan’s leading design house is jovial; there’s loud pop music on and the air is frequently punctuated with bursts of laughter and lots of noisy banter.

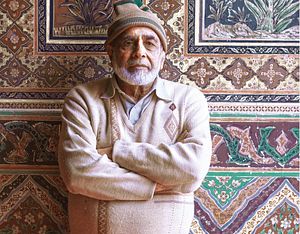

I soon meet him. He’s a sweet, soft-spoken man, dressed in a shalwar kameez and a prayer cap perched on his head. Ustaad Saif-ur-Rehman smiles and greets me. Here he is, standing before me, one of the most eminent master craftsmen of the endangered art of fresco in Pakistan. Yet not many know of him, nor are they aware of Rehman’s extensive work and service to the city of Lahore. Still, that doesn’t bother him. Fame and recognition are not his life’s purpose – art is. It always was.

Currently teaching fresco art at the well-known National College of Arts (NCA) in the city, Rehman has been working with SEFAM for two years. This year, the design house launched a line of clothing under its own brand – Kayseria – titled, “Ustaad Saif-ur-Rehman, Fresco Masters Collection.” The designs for the line were made by the master himself. Through the campaign, SEFAM not only aspires to pay tribute to Pakistani artists such as Rehman, but also to revive and restore local art forms.

From working on the restoration of historical monuments in the city of Lahore for most of his life, the master craftsman now spends his time teaching and focusing on designs for apparel for women.

For an established Pakistani design house to honor a living, breathing, national treasure such as Rehman – and to do so by putting the artist in the forefront of their campaign – is not only laudable, but also moving. In Pakistan, fashion designers and design houses seldom give credit to the creative geniuses behind the finished products; those individuals, far away from the media spotlight, working tirelessly day in and day out.

But wait, we’re not here to discuss fashion, we’re here to talk about Rehman and the art of fresco, an art form that Rehman has loved ever since he was 12-years-old.

“I was in 5th grade when I came to Lahore during my school vacations. I stayed in the city for two months,” Rehman tells me. “It was at that time that I began developing an appreciation for fresco art. I’d sit at the Badshahi Mosque, and while studying, I’d watch artists restore the mosque. I was fascinated. That’s when I realized I wanted to learn the art.”

Born in a small village in the district of Attock in 1942, Rehman moved to Lahore when he was in 8th grade. At the time, there were numerous restoration projects taking place in the city and Ustaad Ghulam Mohiyuddin and Ustaad Ahmad Buksh – Rehman’s teachers – were well-known for their art. “I began working with them,” he states, “I’d mix the colors while they’d do the main work. Slowly I started learning the art – I found it so interesting.”

Rehman’s body of work is vast – he has worked extensively on heritage sites such as the Wazir Khan Mosque, the Mariyam Zamani Mosque, the Lahore Fort, the Badshahi Mosque, Jahangir’s Tomb, Shalimar Gardens, the Governor House, contemporary buildings such as the Serena Hotel (in the capital), and more.

The master craftsman recalls the restoration of the Wazir Khan Mosque in the 1970s, noting that the project wasn’t very successful, initially. “We worked on the mosque from 1970 to 1975, but it didn’t work out the way we’d wanted it to,” he said. This resulted in the government of Punjab putting an advertisement in a local newspaper, calling for children who were interested in learning the art of fresco. “That’s when Ustaad Mohiyuddin and myself began teaching and training children at the Wazir Khan Mosque. You can say the mosque was our head office of sorts; we operated from there, giving workshops and training. When the children were trained, we’d send them off to different sites to be a part of the restoration teams. It was around this time that General Zia-ul-Haq had given orders to fully restore the city’s heritage sites and to bring them back to their original splendor.”

After the restoration of the Wazir Khan Mosque finally culminated, Rehman began focusing on private projects as the bigger restoration projects for the city’s heritage sites came to a close with the passing of a well-known architect, Muhammad Wali Ullah Khan; a man who, in Rehman’s eyes, was the main driving force behind the city’s restoration projects. “After him there was no one else who cared so much about the restoration of these heritage sites,” he said.

However in 2004, a committee (part of a UNESCO-funded restoration initiative) approached Rehman to restore the beautiful Sheesh Mahal (translated as the “Palace of Mirrors”) in Lahore. Interestingly, the Principal of NCA (at the time), Sajida Vandal, who was part of the committee, suggested that Rehman ought to teach at her college. She was insistent.

The craftsman smiles, remembering the incident quite fondly. “I remember telling her: I’m an uneducated man, I don’t know English, what will I do there? Won’t those kids want someone who speaks English? So she said; we don’t need someone who speaks English! We need someone who knows the art and who can teach it! That’s when I started teaching at NCA – I’ve been there since 2006.” Rehman grins.

While the art of fresco remains an endangered art form in the country, does the artist have any hope for its future? “The art only stays alive when there’s someone needing it to be done. Look, if I just sit here and no one asks me to use my art, what do I do? Eventually I’ll give up on it, won’t I? That’s why it’s important to not only have the artists, but also the consumers of art.”

But for Rehman, the intention behind one’s work is also as important, if not, more so. “Those who work with clean intentions, good intentions, those who work hard, God always gives them success,” he says, “No matter what work you’re in; from an officer to a clerk, if you work hard, God will take care of you.”

That said, Rehman mentions that to keep the art of fresco alive in the country, the government has a vital role to play in its survival.

“To keep this art alive, a fund should be created, a committee formed, so that it can be sustained. Now look, we’ve taught our children, but one year of education in fresco art is not enough…how much can a child learn about the art in a year? The government has to do something. This is part of our culture, it’s our own art form, we cannot just let it die out.”

Sonya Rehman is a journalist based in Lahore, Pakistan. She can be reached at: sonjarehman [at] gmail.com