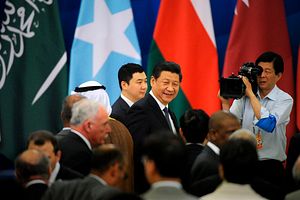

On Wednesday, one week before Chinese President Xi Jinping is reportedly scheduled to arrive in Egypt for his first visit to the Middle East, China issued a lengthy explanation of its approach to the region in a document titled “China’s Arab Policy Paper.” The paper briefly traces the history of China-Arab relations, from exchanges via the ancient Silk Road to the founding of the China-Arab State Cooperation Forum in 2004, before outlining China’s plan for expanding cooperation in the future.

Some caveats, first: like China’s 2015 policy paper on Africa, the “Arab Policy Paper” does not lay out specific policies for specific countries (in fact, there’s not a single country named in the paper, besides China). The paper presents a blanket vision for regional relations, without getting in to the complexities of how that vision will be realized in bilateral relationships with individual states. This is a paper about China’s approach to “Arab countries,” not China’s approach to say, Egypt or Saudi Arabia. For China’s purposes, the “Arab countries” are those with membership in the League of Arab States, which serves as the basis of the China-Arab State Cooperation Forum.

Right now, China’s relationship with the Arab world is largely defined by its energy imports — meaning, of course, oil. As the policy paper notes, “Arab countries as a whole have become China’s biggest supplier of crude oil.” The full truth is even more striking: Saudi Arabia alone is China’s largest supplier of oil, and when you factor in Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, the Arab world accounts for over 40 percent of China’s total oil imports.

Right now, China’s relationship with the Arab world is largely defined by its energy imports — meaning, of course, oil. As the policy paper notes, “Arab countries as a whole have become China’s biggest supplier of crude oil.” The full truth is even more striking: Saudi Arabia alone is China’s largest supplier of oil, and when you factor in Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, the Arab world accounts for over 40 percent of China’s total oil imports.

Small wonder, then, that China sees energy cooperation as the major factor in its approach to the region, and that remains unchanged in the policy paper. According to China’s “1+2+3” formula for China-Arab cooperation, energy cooperation will be the “core” of the relationship, with constructing infrastructure and facilitating trade and investment as the “wings” supporting that core. The “3” refers “three breakthroughs” – a wishlist for future cooperation in nuclear energy, new and clean energy, and aerospace (particularly satellites, but including “cooperation on manned spaceflight”). China’s “Belt and Road” initiative will serve as the framework for all of the “1+2+3” cooperation.

Moving on to more general trade issues, China promises to complete negotiations on a free trade agreement with the Gulf Cooperation Council, comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The policy paper also notes that China supports “the entry of more non-oil products from Arab states into the Chinese market,” addressing a common complaint from China’s natural-resource rich trading partners.

China’s interactions with the Middle East in general are largely limited to the economic sphere right now. The policy paper doesn’t exactly turn that paradigm on its head; the section on “Investment and Trade Cooperation” is over twice as long as the section on “Cooperation in the Field of Peace and Security.” However, there is attention paid to the security realm, an area where China has been noticeably absent in the Middle East.

China’s baseline for security cooperation in the region is so low that promising to “deepen China-Arab military cooperation and exchange” won’t necessarily amount to much, but it is still worth taking note of as part of a larger trend in Chinese military and security outreaches to distant regions. Specifically, China promises to “strengthen exchange of visits of military officials, expand military personnel exchange, deepen cooperation on weapons, equipment and various specialized technologies, and carry out joint military exercises.”

Unsurprisingly, much of China’s proposed security cooperation is set in the context of anti-terrorism, which has become a serious concern for Beijing. “China is ready to strengthen anti-terrorism exchanges and cooperation with Arab countries,” the paper says, with some goals being to “establish a long-term security cooperation mechanism, strengthen policy dialogue and intelligence information exchange, and carry out technical cooperation and personnel training.” However, China also notes, as it usually does when the subject of terrorism is brought up, that “counter-terrorism needs comprehensive measures to address both the symptoms and root causes” – meaning economic development along with military measures. Based on China’s existing strategy for fighting global terror, expect more in the way of financial aid and capacity building support for regional militaries than an increased Chinese military presence to fight terror in the Arab world.

Finally, whether purposefully or not, parts of the paper serve to help distinguish China from the United States, which functions as the major security partner for many of the Arab countries. Unlike the United States, which has strong ties to Israel, China declares its full support for “the establishment of an independent state of Palestine with full sovereignty, based on the pre-1967 borders, with East Jerusalem as its capital.” The policy paper also implies that China’s principles of non-interference will keep it from making pesky human rights criticisms, because “China respects choices made by the Arab people, and supports Arab states in exploring their own development paths suited to their national conditions.”

Overall, the paper doesn’t really add much to already noticed trends in China-Middle Easts relations. Perhaps the most striking thing about “China’s Arab Policy Paper” is that it exists in the first place. China has never before issued a paper outlining its approach to the Arab world; doing so now indicates that Beijing sees a growing strategic importance to the region.