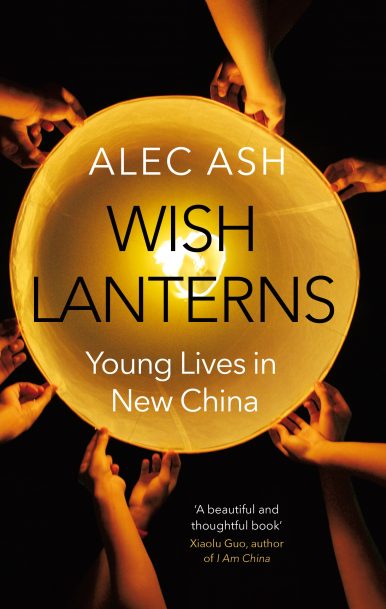

Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China tells the stories of six people from the 1985 to 1990 generation getting by and growing up in the Middle Kingdom. The well-received BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week explores how Chinese millennials have adapted to an ascendant China. As the launch of the U.S. edition on March 7 nears, Alec Ash, journalist and founder of the Anthill blog, sits down with The Diplomat to tell us what this generation has to offer and how individual tales can add to the social narrative.

What’s so special about the 1985 to 1990s generation?

What’s so special about the 1985 to 1990s generation?

I think given the pace of change in China over the last hundred years every generation has a very particular story behind it. This generation interested me primarily because I belong to it. I was born in 1986. When I first came to China in 2008 to learn Mandarin, I became interested in the stories of the people in my age group around me who were born into an already more competent China, a resurgent China, which views itself with more confidence on the world stage, and this is the generation that is going to define the future direction of China over the next decades. I think one of the things that makes them special and which makes it difficult to generalize about them is the sheer diversity. People in their teens and twenties — according to the 2011 census, today there are about 320 million of them [in China], which is nearly the population of the United States — which encompasses a whole gamut of backgrounds and opinions.

Those in Wish Lanterns seem quite optimistic, for the most part. The narrative, it seems, is that Chinese millennials are apathetic, and that’s not something you found with those you spoke to?

I was keen in my approach to simply learn and try to understand the stories of six people of this generation and put it on the page for the reader to interpret how they will. I think one interpretation could be that they are apathetic; at least three of the six characters don’t give a fig about politics and for good reason, as it’s not seen as affecting their own lives. I also wanted to present facts that push back against that stereotype that people just don’t care. I think there’s a difference between apathy and disengagement, and if you view politics as something you have no control over in China, which is the case, that doesn’t mean that you don’t care about the future of your country. And I found a lot of people and wrote about a couple of them that I felt were quite engaged in wider affairs and current affairs in China. One of those, Fred, is quite pro-Party, quite pro-nation; the other, Dahai, is vary anti-authoritarian, but one interesting feature of their narrative is that both have stepped back from that engagement and compromised on it somewhat, and almost given up, which perhaps speaks also to that truth of not being able to influence China as a Chinese.

Speaking of Fred, her hard left turn was quite interesting; you mentioned Tiananmen Square and how she was quite interested in the 1989 event, but then she changed her mind to reflect that it was blown out of proportion by the Western media. Is that the sort of “growing up” mentality?

Exactly. For this generation, they were coming of age in the mid 2000s to present day, and at the same time, China was going through the same growing pains, coming out onto the world stage just as someone in their 20s tries to find their way. I was in China for the same period, and was sort of interested in connecting the individual stories to the wider narrative of the changes the country has been going through.

As it pertains to the post-95 generations, do you see the same attitudes of someone like Lucifer, Dahai, or Xiaoxiao?

Ha, yeah, I don’t get that generation. I’m too old. The generation I write about I regard as a wedge generation, a transitional generation, as China itself was transitioning. If you think about the period of a generation gap in the West, it might be 15 or 20 years but in China there’s a generation gap every three years of five years, so for someone born in 1985, they would still remember China as a much poorer country than it is now. Those born in 1990 or 1995, they would have grown up with China already in the World Trade Organization, as a geopolitical force, and I think that has a roll-on impact into their lives and their world view. That trend, I think, is only continuing. Younger Chinese born in cities, I think, tend to look beyond the traditional and quite constrictive models of success which were foisted on the post-80s generation by their parents: a good gaokao score, good university, stable job in a state owned enterprise or bank.

The nationalism of this generation, these nationalist urges, do you think it harkens back to this generation aching for a past they truly don’t understand? Perhaps a sort of Make China Great Again situation?

Sure, a lot of young Chinese have signed up to the Make China Great Again mission. Nationalism is very powerful and that has always been present in Chinese youth. I recently became interested in young Chinese through a historical lens while reading about the May 4th Movement and of course later the Red Guard and the protests of ’76, ’78, and throughout the ’80s, asking the question: what is the legacy of that today? I think the legacy is in these nationalistic protests, when you go chuck a rock at the Japanese embassy or picket KFC over a ruling in the South China Sea. In that respect, they are temporarily aligned with the direction of the national leadership, but I understand those two forces at the top and at the bottom are two totally separate entities.

Do you expect this new optimism and aspiration to spread from these Chinese millennials to the post-95 generation?

I think one of the reasons why we’ve seen the boom in entrepreneurship and going it alone is because the economic situation isn’t particularly stable, and you’re not guaranteed stability in a regular nine-to-five state-owned job. I’m no economist, but I certainly haven’t noticed, on the social level, any impact on economic decisions; I think there’s still a great sense of confidence on a political level, more confident than ever that China is ascendant.