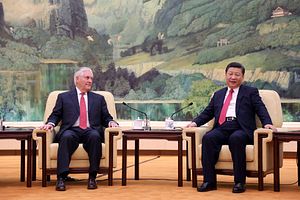

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s first visit to China came to a conclusion this weekend, having visited South Korea and Japan earlier in the week as part of his East Asia tour. As expected, policy options regarding North Korea were a top focus.

Pyongyang’s recent set of missile launches, including a more advanced ballistic missile which landed in the Sea of Japan, tested not only Washington’s patience but also that of Beijing. Indeed, just hours prior to Tillerson’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Sunday, North Korea’s state media reported the testing of a new high-thrust rocket engine, overseen by Kim Jong-un himself who declared it “a new birth” for the isolated country’s rocket industry. So what is the likelihood of China supporting changes in U.S. policy toward North Korea?

Soon after visiting the demilitarized zone during his recent trip to South Korea, Tillerson declared that the U.S. policy of “strategic patience” with North Korea has ended. The remark came after Tillerson’s meeting with Japanese Foreign Minister Kishida, when Tillerson pointed out that “diplomatic and other efforts of the past 20 years to bring North Korea to a point of denuclearization have failed” and that “it is clear that a different approach is required.” This is in line with Deputy National Security Adviser K. T. McFarland’s request, according to a Wall Street Journal report earlier this month, for an overhaul of U.S. policy toward North Korea, including the option of regime change and the possibility of “direct military conflict.”

There is little question whether Japan or South Korea would back a “different” U.S. policy response toward North Korea. However, China’s reception of a new U.S. policy toward North Korea is as of yet unclear, particularly from the perspective of some Washington policymakers who are still trying to determine whether China is a “strategic partner” or a “strategic competitor.”

This is not a new question for Washington. The Obama administration was ultimately unable to formulate an overarching and cohesive policy on Asia, despite its much-heralded attempt at a “pivot to Asia.” George W. Bush, before taking office, criticized the Clinton administration’s so-called “strategic partnership” with Beijing, and instead promised to treat China as a “competitor.”

In a strikingly differing tone over the weekend, Tillerson stated that the relationship between China and the United States was guided by “nonconflict, nonconfrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperation” echoing rhetoric similarly expressed by his Chinese counterpart. Furthermore, both Tillerson and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi indicated a willingness to work together on the North Korean issue.

But if the U.S. is counting on China’s support for a military approach to the North Korea issue, there are some prohibitive factors.

First, there’s the issue of the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) anti-ballistic missile placement in South Korea, which commenced deployment earlier this month. China views the THAAD placement as a threat to its national security and has voiced its concerns accordingly. If the Trump administration were to seek partnership with China on countering the threat from North Korea, the THAAD issue would likely lead to an impasse.

Another factor is the instability that a military option in North Korea would generate. As witnessed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, military conflicts are unpredictable, including in their aftermath. Regime change or military conflict on Beijing’s doorstep would be dangerously destabilizing, notwithstanding the nuclear aspect. Beijing would almost certainly prefer an alternate, more cautious approach. Indeed, China has repeatedly requested a return to the stalled six-party talks which included North Korea, China, Russia, Japan, South Korea and the United States — an offer declined by Obama and looking increasingly unlikely under Trump.

By putting the military option on the table, the Trump administration could be trying to push China into further action on North Korea by its own impetus. After all, North Korea’s recent provocations pressed Beijing to halt its imports of North Korean coal until the end of 2017. This was a bold step by Beijing, considering exports of high-quality coking coal to China account for a large percentage of North Korea’s trade and GDP. With these steps in mind, the Trump administration likely assumes there is more Beijing could do to tame the unpredictable North Korean regime.

The risk in taking this approach is that Trump or his administration — a few of whom have already made intransigent remarks toward Beijing during and prior to Trump’s presidency — could become too adversarial and miscalculate how far they can push China. As a result, Washington could antagonize China further when China could instead be a helpful partner on North Korea.

While considering what “different approach” towards North Korea the United States will take, economic sanctions against Pyongyang are still being implemented. Recently, South Korea and the United States agreed to strengthen cooperation on sanctions and promised to follow through with United Nations sanctions. Combined with China’s embargo on North Korean coal imports, the overall impact on Pyongyang’s economy could be palpable, but is yet to be fully determined.

What it could come down to is how much weight the United States places on military options and on diplomatic solutions. For the United States to count China as a partner, it’ll take leveraging resources and relationships wisely, rather than relying on force.

Christine Guluzian is a post-doctoral visiting research fellow in Defense and Foreign Policy Studies at the Cato Institute.