Russian President Vladimir Putin traveled to Central Asia this week, making stops in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan over the course of two days. The usual topics came up: friendly bilateral relations, the annoying impact of “circumstances” on economic relations, and security.

In Kazakhstan, Putin met with his counterpart Nursultan Nazarbayev in the old capital, Almaty. The leaders traded compliments, as usual, but seemed to have differing perspectives on whether there were any problems in the bilateral relationship.

Nazarbayev began his remarks, per a Kremlin transcript, by noting that “[i]t is our tradition to meet at the start of the year to set our watches and outline our plans and our work together.” He emphasized that through 25 years of relations the two states have built up “the kind of model relations that countries that are good friends and neighbors should have.”

After a shout out to the Eurasian Economic Union and a vague lament that “[t]here is no getting away from the fact that circumstances have had an impact, of course,” Nazarbayev highlighted Russian businesses in Kazakhstan and their shared approach on the international stage.

Then Nazarbayev got to this interesting aside: “Let me say that our delegation has no issues to raise with the Russian delegation… All current matters are settled in friendly spirit and I see no problems.”

Putin, when it was his turn to speak, thanked Nazarbayev and Kazakhstan for hosting talks on Syria recently. He went on to recast fallen trade turnover numbers as essentially a math problem, the result of fluctuations in global markets — fallen in value terms but not physical terms.

Putin ended his statement, however, on a different note than Nazarbayev: “Of course, as in any undertaking, there are difficulties and problems that require attention from our countries’ leaders, and I hope that we will discuss all of these matters during our meeting today.”

Nazarbayev had no problems to discuss, but Putin, apparently, did.

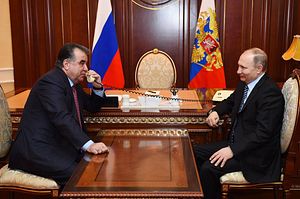

After meeting with Nazarbayev, Putin flew to Dushanbe, Tajikistan to meet with President Emomali Rahmon. The Tajik leg of his regional tour focused more heavily on security issues and bilateral, rather than multilateral, economic issues. Despite rumors, no mention was made publicly about Tajikistan considering membership in the Eurasian Economic Union. While TASS reported that “a number of documents” were to be signed and RFE/RL highlighted talk about strengthening security on the Afghan border, EurasiaNet summed the visit as a “damp squib,” noting the most movement possibly stemming from comments about Tajik labor migrants facing bans in Russia.

On Tuesday, Putin traveled to the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek. There he met with President Almazbek Atambayev. Kyrgyzstan, in some ways, is the most interesting of the three stops due to recent and ongoing events that either directly relate to Russia or do so in a significant, but tangential, way.

One recent event that shines a sour light on Russia is the issue of the flight of a Russian diplomat involved in a fatal car accident. On February 16, the first secretary of the Russian Embassy in Bishkek, Viktor Pukhov, ran a red light. The embassy’s car, a Toyota Land Cruiser Prado, smashed into a van driven by a Bishkek resident. The man, Alesei Leksin, died en route to the hospital and Pukhov has returned to Russia.

The accident prompted an outcry on social media and by the man’s relatives but has been overshadowed by protests relating to the recent detention of Omurbek Tekebayev, the head of the Ata-Meken party. While Russia is unrelated to Tekebayev’s detention, both the arrest and Putin’s visit have stirred up a regional tradition: speculating how much (notably, not whether) Russia is involved in Kyrgyzstan’s politics.

In Kyrgyzstan, Atambayev and Putin held a joint press conference and therefore had to address — or at least dodge — questions.

One journalist asked first about a rumored expansion of the Kant Air Base — Russia’s base outside Bishkek — and then about whether Russia got “assurances that the transfer of power this fall in Kyrgyzstan will go smoothly?”

Atambayev backed away from the Kant question and said that Putin didn’t even raise the issue of Kyrgyzstan’s looming power transfer. Atambayev, never one to pass on grandstanding, went further:

…I can say that should anyone think about staging a revolution in Kyrgyzstan, just remember that it was Atambayev who was the leader of the past two revolutions. In 2005, I headed the procession that occupied the White House. In 2010, you may recall where people assembled to voice their protest. It was near my office. So, if a third revolution takes place, I will not be the one to stage it.

Let me put it this way, there will be no more revolutions in Kyrgyzstan. We cannot afford to have a situation described in a song: ‘Revolutions have a beginning with no end in sight.’ Mr Putin used to tease me with this song. We have to get down to work…

Putin gave a brief history lesson regarding Kant — the base was established in 1999-2000 at the request, he said, of the Kyrgyz and targeted at dealing with terrorists from Afghanistan — and placed its fate in Bishkek’s hands: “When Kyrgyzstan decides that it has strengthened its armed forces so that it no longer needs this base, we will pull out immediately.”

He then went on to address the implied interest Moscow has in the Kyrgyz presidential elections with a comment some — especially in Ukraine, perhaps — may find reason to quibble with:

As for internal political processes, they are not our business and we never interfere in internal processes of other countries, let alone our allies.

In total, Putin’s Central Asia tour was a walking of familiar paths, repeating familiar platitudes and shaking the same hands over the same assurances. Russia remains the region’s oldest friend, even if it has not always been the best of partners.