By any measure, RIMPAC 2018 is huge.

This year’s Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise in Hawaii and southern California includes the military forces of 25 nations and 25,000 personnel. For 37 days this summer, 200 aircraft, 46 ships, and five submarines are training to cooperate in conflict, with an array of joint exercises in the air, on land, and at sea.

The biennial exercise includes infantry integration, urban combat training, amphibious operations, sniper reconnaissance training, ship sinking exercises, missile, rocket, and torpedo launches, navigation exercises, shore to ship maneuvers, explosive ordnance disposal, and more.

RIMPAC 2018 has also added Vietnam and Sri Lanka. Brazil, too, was invited but dropped out due to a scheduling conflict.

According to a RIMPAC media officer, the exercise offers “realistic, relevant training” and “improves the U.S. Navy’s readiness… to operate globally.” RIMPAC’s cost to the United States has been allocated in training budgets, with an additional $2.09 million required for staffing and execution. All other nations cover the cost of their own participation, the officer said.

Organizers are quick to frame RIMPAC in terms of fostering international cooperation and trust building while emphasizing the HADR (humanitarian assistance disaster relief) component of RIMPAC, but critics contend RIMPAC’s ultimate purpose is to train for war and is a boon for the arms industry.

This year’s RIMPAC began with a four-day innovation fair that featured 22 exhibition booths and demonstrations of “innovative ideas and capabilties” for warfighters. On display were examples of the latest VR and simulation tools, robotics, drone systems, data and information exchange, port security, and other military-related technology.

An Australian Army sniper with 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, sights in on a target with a Blaser Tactical 2 sniper rifle during live-fire training as part of Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise at Pohakuloa Training Area, Hawaii, July 14, 2018. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Adam Montera)

A Feast of Firsts

RIMPAC planning coordinator Royal Australian Navy Lt. Cmdr. Dean Uren listed a number of firsts this year, which included:

- A non-founding RIMPAC member (Chilean Navy Commodore Pablo Niemann) serving as Combined Forces Maritime Component Commander

- Participation of naval ships from Malaysia and the Philippines

- Joint U.S and Japan ground forces firing rockets as part the first of two SINKEX (ship sinking exercises)

- Participation by Sri Lanka, which sent a platoon of marines to conduct amphibious operations and live fire training

- Participation by Vietnam, which sent four staff involved in an HADR exercise

- Participation by Israel, which sent one officer to assist in RIMPAC planning and execution (no aircraft or military equipment was sent)

Uren said the idea behind introducing countries from outside the Asia-Pacific is to build partnerships because open seas are critical to global commerce and trade. First-time participation tends to be small, Uren said, but “once they come to appreciate the scale and opportunities that RIMPAC provides to their nation, we tend to see expansion into other areas within the exercise.”

Too Militarized for the Military

One notable absence from RIMPAC 2018 was China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), which took part in RIMPAC 2014 and 2016 but was disinvited in reaction to its deployment of anti-ship and surface-to-air missile systems as well as electronic jammers in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

In a statement, U.S. Defense Department spokesman Christopher Logan called on China to “remove the military systems immediately and to reverse course on the militarization of disputed South China Sea features.”

Logan described China’s behavior as “inconsistent with the principles and purpose of the RIMPAC exercise,” adding that the “placement of these weapon systems is only for military use.”

The disinvitation didn’t stop China from observing from the sidelines, reportedly sending at least one spy ship to waters near Hawaii.

Sailors assigned to the “Grey Knights” of Patrol Squadron (VP) 46, the “Broad Arrows” of VP-62, and the “Totems” of VP-69 load an AGM-65 Maverick missile onto a P-3C Orion aircraft on Marine Corps Base Hawaii during Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, July 19. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Kevin A. Flinn/Released)

Preparing for the Next Fight

Meanwhile, RIMPAC continued in southern California where U.S. marines trained with their counterparts from Mexico (Fuerza de Infantería de Marina) and the Canadian army for a trilateral military urban ops and infantry training exercise.

In Hawaii, U.S. marines partnered with forces from Chile, South Korea, and the Philippines to practice clearing urban areas and tactical training methods employed around the world while an All-Weather Marine Attack Squadron conducted night ordnance missions from Kaneohe Bay, Oahu.

At Pohakuloa Training Area (PTA) on Hawaii Island, land forces from Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Japan, Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, New Zealand, Tonga, Chile, and the United States conducted a week of war games.

PTA, the largest U.S. military installation in the Pacific, has multiple ranges for small arms fire training, joint operations, static live fire exercises, and squad sized attacks and an impact area for artillery and mortar training.

U.S. Marine Major Vincent Thompson, operations officer for 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, praised RIMPAC as a rare opportunity to practice integrating ship-to-land connections, and coordinate with supporting aircraft. Exercises involve vehicles, equipment, and soldiers traveling in convoys from ship to shore, across Hawaii Island and up to the high altitude (6,300 feet) PTA between volcanoes Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea and just 30 miles from the ongoing eruption of Kilauea.

Thompson explained that PTA, with its rugged lava rock terrain and open space (PTA is as large as the entire island of Guam), allows soldiers to practice integrated training with partner nations that includes mortar, artillery, rocket, and ordnance live fire exercises, use of Raven and Puma surveillance drones, and other weapon systems.

Soldiers appreciate the exercises, too. During a joint U.S.-Australia sniper training, one U.S. Marine described his favorite part of being a sniper: “I love being able to sneak up on people and them not knowing I’m there and their life is in my hands.”

Thompson praised partner nations, saying, “We have a lot of countries coming in that have combat experience that is a higher level of depth than our own, especially recently.”

The joint training allows participants to apply real world experience and “hard lessons learned,” Thompson said, adding, “It’s been eye opening for the Marines to see that the next fight we go to, likely we’re not going to be alone. We’re going with some real capable people.”

The guided-missile destroyer USS O’Kane (DDG 77) launches a Standard Missile-2 during a Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) live-fire event July 16, 2018, in the Pacific Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Raymond Minami)

The Sound of Violence

But not everyone is excited about the war games. While little media attention has been given to critics, some Hawaii residents want to see the exercise scaled back or ended all together. RIMPAC opponents cite a litany of concerns including environmental damage, the impact of sonar on marine mammals, opposition to Hawaii serving as training grounds for war, negative social impacts like prostitution and sex trafficking, and an affront to Hawaiian sovereignty.

As with past RIMPACs, opponents have staged demonstrations and other events on Hawaii Island outside PTA’s front gate, on Kauai, and on Oahu.

At a protest outside the Headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, demonstrators chanted “Aole RIMPAC!” (No RIMPAC!) and carried signs denouncing military training and operations everywhere from Okinawa and West Papua to Gaza and Syria.

A Slap in the Face

Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp is a Hawaiian cultural historian who would like to see RIMPAC downsized or removed altogether. He said many Native Hawaiians see RIMPAC as a legacy of Hawaii’s colonization. He’s referring to the 1893 overthrow of what was the sovereign, independent Hawaiian Kingdom with the backing of U.S. Navy and Marines.

When considering the land, water, and airspace controlled by the military in Hawaii, Manalo-Camp asked, “How did [the military] acquire so many resources?” He answered his own question, “What the military didn’t acquire through dispossessing the Hawaiian government, they acquired by disposing private land owners.”

Manalo-Camp acknowledged speaking critically can be difficult in Hawaii, where many depend on the military for their income, but added, “for many younger Hawaiians, RIMPAC is seen as a slap in the face because of our history and because of the fact that so many local people have to move away from Hawaii in order to find economic opportunity.”

U.S. Marines assault a building with Australian Army soldiers from the 2nd Battalion (Amphibious), Royal Australian Regiment, during urban operations training at Marine Corps Base Hawaii during Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise 2018. (Photo by Royal Australian Army CPL Kyle Genner)

RIMPAC Impact

For its part, military personnel have said they’ve been warmly received. Lt. Cmdr. Uren commented, “The participants of RIMPAC look forward to coming to Hawaii… because of the beauty of the island, the friendliness of the people, and the world class facilities that we get to leverage as part of this exercise.”

He continued: “We appreciate Hawaii for allowing this critical training to take place.” In response to environmental concerns, Uren said there are procedures in place to minimize any potential impact to the environment whether on land, in the air, or at sea. The importance of being “good stewards of the environment,” Uren said, is a focus of the exercise.

While critics see RIMPAC in terms of bombs and bullets, many in Hawaii’s local government and business community view RIMPAC as an economic windfall. In an emailed statement, Sherry Menor-McNamara, president and CEO of the Chamber of Commerce Hawaii, said hosting RIMPAC was “an honor as well as a benefit to many businesses in Hawaii.”

According to Navy Region Hawaii spokesman Bill Doughty, RIMPAC in 2016 and 2014 both achieved more than $50 million in “direct benefits to Hawaii” and the same is expected for 2018.

“The biggest economic benefit to the state comes from the security and stability RIMPAC builds in the Pacific,” Doughty said. “That security and stability lead to prosperity and the free flow of commerce, which is especially important here in Hawaii.”

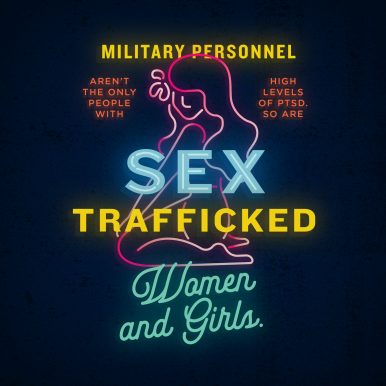

Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women launched its first anti-trafficking campaign to coincide with RIMPAC and aims to bring attention to the outsized demand for prostitution in Hawaii. Photo provided by the Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women.

Taking Liberties

A RIMPAC media spokesperson noted that visiting RIMPAC soldiers enjoy “liberty options” like hiking, surfing, and watching turtles on the north shore of Oahu and going downtown to enjoy off-base dining options and different liberty spots.

In the military, “liberty” suggests freedom and enjoyment, but Khara Jabola-Carolus, executive director of the Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women, sees a problem with the influx of an additional 25,000 military personnel to Hawaii.

This year, the commission launched the first-ever anti-sex trafficking and prostitution campaign during RIMPAC, when concerns about coerced sex trade rise even as activity grows increasingly invisible, moving from public spaces to social media and “sugar daddy” websites, which list specific pages for Hawaii’s military bases where solicitors openly identify as military personnel.

While trying to raise awareness of the campaign in drinking establishments that cater to RIMPAC soldiers, Jabola-Carolus said she faced open hostility from business owners and was warned to stay away.

Jabola-Carolus said the military breeds a culture of violence and domination. “There’s a serious problem of male violence within the military… So the bigger the presence, the bigger that culture, the more it’s going to seep out, and how can you contain that, even if you have some people really committed to that end,” Jabola-Carolus asked.

She recognizes the military is a pillar of Hawaii’s economy but said, “it’s a pillar that has got women pinned underneath it.”

Jabola-Carolus added, “The bottom line is that traffickers will go to where money can be made. This is not a new phenomenon or one limited to RIMPAC, although RIMPAC is how we chose to open the campaign. This year Hawaii will host over 9.3 million tourists and nearly 90,000 soldiers. It’s an everyday problem given how we have structured our local economy.”

Out of Step With Our Values

Outside of Hawaii, there’s almost no public awareness of RIMPAC. Even in Hawaii, many residents have scant knowledge of the exercise. University of Hawaii associate professor of political science and indigenous politics Noe Goodyear-Kaopua said RIMPAC is “out of step with our core Hawaiian values of aloha aina (love for the land).” She called the war games a “demonstration of violent power.”

For her, RIMPAC is one outcome of the overthrow, occupation, and decades of the U.S. using Hawaii as a military platform from which to project power and influence across the Asia-Pacific.

She pointed to the ballistic missile false alarm that terrified Hawaii residents last January as a “potent reminder” that Hawaii has been and remains a potential target because of the military presence. “RIMPAC for me is one huge reminder of that. I don’t feel proud that we are somehow involved.”

Despite the tone of international cooperation of 25 nations coming together for war games, Goodyear-Kaopua isn’t convinced. “Maybe there’s collaboration among militaries, but in terms of what that does for civilians and ordinary people, I don’t see that as fostering a spirit of international collaboration and unity,” Goodyear-Kaopua said. “At the end of the day, militaries are for war.”

Jon Letman is a Hawaii-based independent journalist covering politics, people, and the environment in the Asia-Pacific region. He has written for Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy in Focus, Inter Press Service and others.