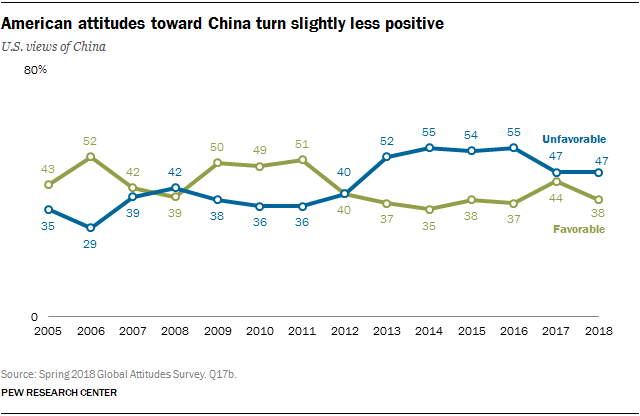

U.S. public opinion toward China has soured over the last year, amid tough talk on trade from President Donald Trump – but remains largely in line with China’s favorability rating from 2013-2016. That’s according to a new survey of U.S. public opinion toward China by the Pew Research Center published on August 28.

The survey finds that “Overall, 38% of Americans have a favorable opinion of China, down slightly from 44% in 2017.” However, last year’s 44 percent favorability rating for China was something of an outlier; from 2012 to 2016, that figure stayed between 40 and 25 percent. Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans with an unfavorable view toward China stayed constant this year at 47 percent, after ranging from 52 to 55 percent from 2013-2016.

As has long been the case, there is a noticeable generation gap in U.S. perceptions of China. Younger Americans (aged 18 to 29) are the most likely to have a favorable view of China; in fact, a plurality (49 percent) of respondents in this age group view China favorably. Among the 50+ age group, that figure drops to 34 percent. This may be an indication that China’s long-term soft power push – including Confucius Institutes designed to teach young Americans Chinese language and culture – is paying off. But it could also simply reflect lingering Cold War-era animosities from older generations that are not impacting the views of the under-30 crowd.

Despite headlines about China as a military and strategic threat, most Americans are far more worried about China’s economic growth than its military prowess. “Nearly six-in-ten Americans (58%) believe China’s economic power is the greater threat,” the Pew Center finds, compared to only 29 percent who believe “China’s military strength” is more of a concern.

That focus on economic issues is borne out in questions about specific issues in the U.S.-China relationship. Chinese holdings of U.S. debt and cyberattacks from China were the two issues most commonly rated a “very serious” threat – at 62 percent and 58 percent, respectively. “The loss of U.S. jobs to China” was third, tied with concerns over “China’s impact on the global environment” (both issues had 51 percent of respondents saying these are “very serious” problems).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, self-identified Republicans were more concerned about the economic issues than Democrats. After all, it is a Republican president and administration that has set off the current trade war, backed by fiery rhetoric about Chinese “cheating” on trade.

However, the Pew Center noted that “[w]orries about job losses, debt and the trade deficit are actually less common today than in 2012, when the economic mood in the U.S. was generally more negative.” That suggests general economic conditions in the country have more impact on U.S. attitudes toward China than top-level rhetoric and policymaking.

Meanwhile, two of the most high-profile strategic concerns for U.S. policymakers – China’s territorial disputes with neighbors and cross-strait tensions between China and Taiwan – did not register the same level of concern. Only 34 percent of respondents said China’s territorial disputes were “very serious problem,” and only 22 percent thought the same about “tensions between China and Taiwan.”

The survey data hints at the impact of U.S. government rhetoric and policy on public opinion toward China – but also reveals the limitations of that impact. Despite the brewing trade war, concerns about China generally and its economic and trade practices specifically registered only marginal increases from 2017, and are in fact down from previous highs during the Obama administration’s second term. Meanwhile, a new public focus by policymakers and elites on China as a military and strategic rival is barely registering for the average American.