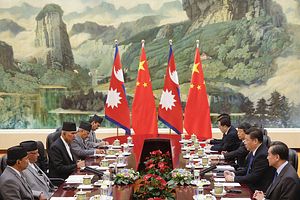

In a surprise move last week, Nepal was granted access to Chinese land and sea ports, ending Kathmandu’s dependence on Indian ports. While the move is just one of several within the bilateral relationship, it nonetheless deserves attention for its potential wider significance.

In March 2016, Kathmandu and Beijing signed a Transit and Transport Agreement (TTA) that promised to provide Nepal access for third party trade through Chinese sea and land ports. The decision to implement the TTA was taken after the two sides signed a TTA protocol in a bilateral meeting in Kathmandu last week. Until now, Nepal had to engage in third party trade through the Indian port in Kolkata in West Bengal (Nepal has a similar access pact with Bangladesh as well).

The TTA protocol allows Nepal access and use of four Chinese sea ports – Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang, and Zhanjiang – and three dry ports – Lanzhou, Lhasa, and Xigatse. With the signing of the protocol, Rabi Shankar Sainju, Joint-Secretary at Nepal’s Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies (MoICS) said, “Now we have access to additional ports as an alternative. They can be used in trading with the countries in east and north-east Asia.”

There are considerable infrastructure development issues to be resolved before these can be totally operational, but ending the dependency on India is seen as particularly a “joyful” moment in Kathmandu. India’s “unofficial” blockade in 2015 had a lot to do with Nepal’s open embrace of China since then. The blockade that led to serious hardships for ordinary Nepalese citizens has created large pockets of anti-Indian and correspondingly pro-China sentiments within Nepal.

Though this is a considerable setback for New Delhi, India has been attempting to play harder for Nepalese affections especially in terms of building up infrastructure for Nepal. India is currently in the process of constructing two railway lines and there are three additional lines being planned to beef up Nepal’s options. India is also refurbishing and upgrading four major custom checkpoints at Birgunj-Raxaul, Biratnagar-Jogbani, Bhairahawa-Sunauli and Nepalgunj-Rupediya in addition to expanding and renovating the road network in the Terai region of Nepal. In addition to Kolkata, India has also opened the port of Visakhapatinam to Nepal and there is a small amount of trade taking place through it. Between India and Nepal, there are reportedly 25 crossing points, two integrated checkpoints, and there are two additional checkpoints being developed now.

The latest TTP is one more iteration of the growing Nepal-China multifaceted relationship. And there are clearly strategic consequences to this growing relationship. One important impact of the Nepal-China TTA is that Nepal’s access to Chinese ports will be through six checkpoints at Rasuwa, Tatopani (Sindhupalchok), Korala (Mustang), Kimathanka (Sankhuwasabha), Yari (Humla), and Olangchung Gola (Taplejung). These and other road and railway projects between China and Nepal will allow China to potentially project power against India on a different section of the Sino-Indian boundary, and possibly even outflank Indian military forces at the border.

As a follow-up to an earlier assurance by China to support mega infrastructure projects in Nepal, Nepal’s Minister for Physical Infrastructure and Transport Ramesh Lekhak suggested to his Chinese counterpart that the connectivity projects should be speeded up since Nepal’s endorsement of the Belt and Road Initiative. A projected route includes connectivity from Kerung in China all the way to Kathmandu, Pokhara, and Lumbini. Lumbini is just about 100 kilometers from the Indian border state of Uttar Pradesh, making it uncomfortably close to the Indian capital.

The expanded and deepened Nepal-China relationship also restricts India’s own strategic space in its own backyard. The growing profile and role of China in South Asia is becoming more prominent, with Beijing making unprecedented penetration in other countries in the region such as Sri Lanka and Maldives. Despite caught up in a debt-trap diplomacy with China to the point of being forced to lease the Hambantota Port to China for 99 years, Sri Lanka does not appear to have learned any lessons: Colombo has gone back to China for more funds to address its next debt repayment cycle in 2019.

China’s successes leave other major powers in a bit of a quandary. While the United States, Japan, and India are all stepping up their efforts to warn poorer states of the dangers involved in seeking Chinese infrastructure funding, their incapacity or unwillingness to provide any credible alternative means China’s is the only real game in town.