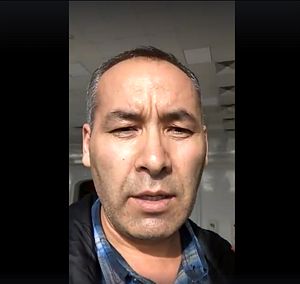

Central Asia is yet again embroiled in China’s ongoing crackdown on Muslim minority groups in its farwestern region. In a series of videos posted online, Halemubieke Xiaheman, a Chinese-born Kazakh businessman, said he was fighting attempts by Beijing to return him to China from neighboring Uzbekistan. His current whereabouts are unknown.

China has clamped down severely on its Muslim minority groups, especially Uyghurs, who are native to the Xinjiang region, but also Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and others. Chinese authorities have detaining an estimated 1 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and others in re-education camps where they are forced to renounce their native culture and the Islamic religion and pledge loyalty to Communist Party leader Xi Jinping.

China claims that its re-education camps are actually “vocational centers” meant to “de-extremify” Muslims and train them for gainful employment. China says such steps are necessary to counter terrorism and separatism in the region. Beijing has tightened its control over the Uyghur homeland since a deadly riot in 2009 between Uyghurs and the majority Han Chinese population in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, and sporadic ensuing violence blamed on Islamic separatists in the years after.

In this particular incident, Xiaheman had filmed a video from inside the transit zone at the airport in Uzbekistan’s capital, pleading for help, saying the Chinese Embassy there wanted him sent back to China. That video was distributed Thursday; over the next two days he released several more videos pleading his case.

According to RFE/RL, Xiaheman’s first video contained a personal appeal to Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev as “a brotherly Turkic-speaking Muslim man” not to give in to Chinese pressure to deport him. “In another video,” RFE/FL added, “Xiaheman… urged the U.S., German, Japanese, British, and Canadian authorities to prevent him from being extradited.”

He apparently succeeded in catching Washington’s attention. A spokesman for the U.S. Embassy in Beijing said Monday that the embassy was aware of Xiaheman’s situation and was in close touch with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees and “relevant governments” on his case.

“We urge third countries to allow UNHCR and other UN organizations and nongovernmental organizations access to these asylum seekers to assess their protection claims and provide assistance,” the spokesman said in an emailed response to a question from The Associated Press.

The Uzbek foreign ministry issued a statement saying he flew to Bangkok on Saturday.

“We inform that he did not enter the territory of Uzbekistan and on February 9, 2019 flew out to Bangkok,” it said.

It wasn’t immediately clear whether Xiaheman had arrived in Bangkok. The UNHCR office in Thailand said it was unable to comment due to confidentiality rules.

Thailand has a mixed history on deporting Uyghurs back to China. Bangkok has deported groups at times, but occasionally refused to do so — particularly when faced with international pressure.

The Uzbek foreign minister statement said Xiaheman had earlier flown from Thailand to Almaty, Kazakhstan after transiting in Tashkent, but gave no details. RFE/RL cited a Kazakh newspaper as reporting that Xiaheman had been sent back to Tashkent’s airport after being refused entry to Kazakhstan “for unknown reasons.”

This isn’t the first time Kazakhstan has found itself pulled into China’s crackdown on Muslim ethnic minority groups. As Catherine Putz reported for The Diplomat, Astana faced a difficult choice last year when an ethnic Kazakh Chinese citizen, Sayragul Sauytbay, sought asylum in Kazakhstan. Sauytbay, whose husband and children are Kazakh citizens, had fled from the re-education camps, were she was forced to be a teacher.

As Putz noted:

The case put Kazakhstan in a bind, caught between international political and economic concerns — China is one of Kazakhstan’s largest trading partners — and domestic pressure. Existing anti-Chinese sentiments have been inflamed by news of “re-education” camps in Xinjiang imprisoning ethnic Kazakhs and the release of a handful of Kazakh citizens detained in China.

Kazakhstan tried to thread the needle by refusing to deport Sauytbay back to China (she had entered Kazakhstan illegally, hardly surprisingly given the nature of her arrival) but also rejecting her asylum claim. If it’s true that Xiaheman was refused entry to Kazakhstan, it’s possible that the Kazakh government was trying to avoid another high-profile headache like the Sauytbay case.

Though their governments would prefer not to get involved, civil society groups in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have been organizing to call attention to the plight of Muslims held in China. Even Kazakh and Kyrgyz citizens have sometimes been detained – or simply disappeared – when crossing the border to visit relatives in China. Governments in both Astana and Bishkek – more so in Kazakhstan – have put pressure on the groups to stop their work, but so far to no avail. In fact, it was a group of Kazakh activists that first helped distribute Xiaheman’s videos pleading for help.

Numerous Western nations have called previously on Beijing to close the camps and end persecution of its Muslim minority groups. To date, Central Asian governments have tried their best to avoid taking a strong stance. However, nationalism at home is a potent force and cannot be ignored entirely. As Putz pointed out, Kazakhstan has had to issue statements reassuring the public that it brings up the issue of ethnic Kazakhs in discussions with China. Beijing gave Astana a boost on that front by announcing in January that 2,000 ethnic Kazakhs in China would be ‘allowed’ to leave the country.

Meanwhile, on Saturday Turkey broke its own longstanding silence on the Uyghur issue. Turkey’s foreign ministry issued a statement calling China’s treatment of Uyghurs “a great cause of shame for humanity,” in a rare show of public criticism by a majority Muslim nation.

Christopher Bodeen for Associated Press contributed reporting.