The U.S.-China relationship under the leadership of presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping has been volatile. Though differences over trade practices remain the most salient form of discord, both Washington and Beijing have steadily ramped up their tough rhetoric to describe the bilateral relationship. While many may want to cast aside rhetoric as “just talk” or “empty words,” the framing of interstate dynamics can have profound effects that trickle down from the top echelons of political power to everyday citizens.

Earlier this month China-focused scholars, foreign policy, and business leaders penned an open letter to the Trump administration condemning the current U.S. policy toward China and warning against painting Beijing as an enemy. Others have argued that no such “engagement” policy toward China was ever fully in place. Others still have instead noted that Trump’s approach, having abandoned Washington’s previously more cooperative policy, is an overt signal to China that the international status quo that assisted China’s rise is now broken. In other words, some read Trump’s position as communicating that the United States should not and will not quietly acquiesce to China’s emboldened pursuit of status and influence.

Examples of more adversarial rhetoric are manifold. An early indication came in the form of the 2018 U.S. National Security Strategy, which described the current international climate as the scene of “fundamental political contests” between repressive and free societies. In October of the same year, in a speech critical of China, Vice President Mike Pence said, “Beijing is pursuing a comprehensive and coordinated campaign to undermine support for the President, our agenda, and our nation’s most cherished ideals.” More recently, the U.S. State Department’s director of policy planning, Kiron Skinner, made headlines after suggesting that the U.S.-China clash would be a “a fight with a really different civilization and a different ideology.”

However, such escalatory rhetoric is not only a product of the Trump administration; instead, the use of extreme rhetoric and pronounced mistrust or suspicion of China has grown to be a more pervasive facet of American political discourse. Members of the U.S. Congress and Democratic presidential hopefuls alike have opted for more hawkish China positions.

Wisconsin Congressman Mike Gallagher wrote in July that to win in the great power competition, “[The United States] will have to relearn the lost art of ideological warfare.” Other bodies that recommend policy options to the U.S. legislature, including the Congressional Executive Commission on China (CECC) and the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), have furthered a more stringent approach to China. The CECC’s latest annual reports said that “China’s authoritarianism at home directly threatens our freedoms as well as our most deeply held values and national interests”; the USCC found that “In word and deed, the CCP has abandoned any inclination for economic and political liberalization.”

For its part, China has not shied away from using strong language, either. This is especially true when it comes to sensitive political issues such as China’s territorial integrity, namely Taiwan, or China’s domestic policies.

Cui Tiankai, the Chinese ambassador to the United States, and a recent addition to the Twitter-sphere, has already used the platform to decry any attempts to formally sever Taiwan from China, warning such acts would be met with swift and harsh retaliation. That’s no doubt a message for multiple audiences as Taiwan prepares for a 2020 election and as the U.S. moves forward with an arms sale package to the island.

#Taiwan is part of #China. No attempts to split China will ever succeed. Those who play with fire will only get themselves burned. Period.

— Cui Tiankai (@AmbCuiTiankai) July 12, 2019

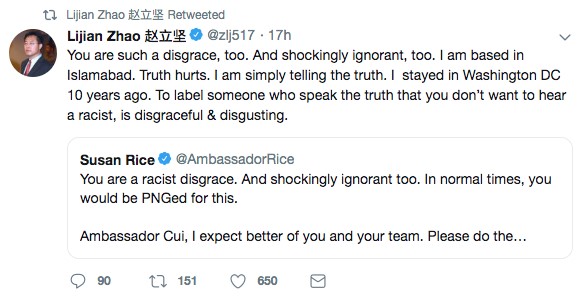

While the tone from Cui was more typical rhetoric, China’s deputy chief of mission in Pakistan, Zhao Lijian, had a more unusual recent Tweet storm. What started as a defense of China’s policy in Xinjiang earlier this week escalated rapidly. Zhao criticized the United States for its human rights record broadly, citing issues related to foreign policy in the Middle East, Islamophobia, racism, immigration, income inequality, gun violence, gender inequality, and sexual assault. A few tweets contained stereotypes about a D.C. neighborhood that led Zhao and former U.S. Ambassador Susan Rice to condemn each other as racist.

Some of the tweets have since been deleted, signaling that Zhao’s tirade may have been the result of an emboldened diplomat acting on his own. However, the increased use of English language-dominant social media platforms (not to mention platforms blocked by the Great Firewall of China) suggests that diplomats and Chinese journalists from state-run outlets may be increasingly willing to voice counternarratives meant for the rest of the world. A Global Times editorial even went so far as to say, “Chinese media and diplomats will act more actively to make the truth known to all and unmask Western pride and prejudice.”

The increased frequency of extreme rhetoric can engender a series of repercussions. First, antagonistic frames of an “other” or an “enemy” are often mutually reinforcing and entrench already present nationalistic sentiments. Regardless of a country’s political system, these dynamics force politicians and diplomats to operate within a smaller scope, with less flexibility, and subject to more public scrutiny. Ultimately, not only do high-level people-to-people exchanges suffer, but the volume of cross-cultural, business, or academic exchanges may contract and their value may be diluted within the larger understanding of bilateral relations.

Despite ongoing and reciprocal finger pointing, the reality is that there is agency and culpability in both Washington and Beijing for the current trajectory of U.S.-China ties. Policymakers in both capitals would be wise to revise their expectations and outlook toward managing arguably the world’s most consequential bilateral relationship. This would require outlining conditions under which the two countries are able to cooperate, compete, and mitigate confrontation. An even more important task will be untangling how these conditions change over time.