Accounts about the disease started sporadically. Somewhere in China people were getting sick in unusual numbers. Then press reports started appearing. Large numbers of people were getting seriously ill along main transport axes. News of deaths soon followed. In a few months 60,000 people would die before the disease came under control. This was not Wuhan in December 2019 and January 2020; it was northeastern China from late 1910 to early 1911. The Manchurian Plague, as the incident came to be known, was the first instance of modern techniques being applied to a public health crisis in China. Lessons of transparency and transnational cooperation from that event more than a century ago are still relevant to China and the world today.

In 1910 and 1911, Manchuria was nominally under Chinese control, but years of foreign incursion saw Japan, Russia, Britain, France, Germany, the United States, and others jostling for power in the region. These foreign actors blamed the Qing government, then running China, for not doing enough to stem the spread of plague. The disease was allegedly transmitted from marmots to humans and later evolved to rapid human-to-human transmission. In response, the Qing court-appointed Wu Lien-teh (伍連德), an ethnically Chinese, Cambridge-trained doctor and public health expert who was born and raised in the British colony of Penang, to fight the plague.

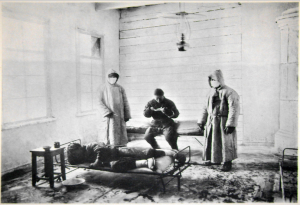

Wu, together with his colleagues in China and abroad, implemented several familiar measures. They came to an early consensus that quarantine and isolation were the best ways to solve the problems and developed a variety of methods, some highly authoritarian, to stem the plague. They insisted on mask-wearing among medical personnel, demanded the cremation of infected bodies, imposed travel restrictions on affected reasons, built up quarantine facilities, and imposed strict home-quarantine. Officials rounded up locals using wagons, holding them until they were no longer symptomatic, disinfected houses that held suspected patients (against their owner’s wills), and forcibly quarantined people in hospitals.

The steps Wu and his colleagues took anticipate action by today’s Chinese government, notably the construction of a special care hospital in 10 days and the use of drones to ensure that residents not leave their homes unnecessarily and without a face mask. Such measures to control the 2019 novel coronavirus (officially known as COVID-19) outbreak suggest an unpleasant level of encroachment on personal rights, with which Wu and his colleagues would likely agree.

Yet draconian quarantine and isolation methods may not have been the only factors in Wu’s success in bringing the Manchurian Plague under control. Wu and his colleagues were remarkably open, transparent, and international in their approach to the health crisis, to the extent of stepping on the sovereignty of the Qing state at a moment of terminal weakness and intense great power pressure.

Wu made epidemiological and other medical information regarding the Manchurian Plague public and convened an International Plague Prevention Conference in April 1911. In doing so, Wu invited scientific members of the international community to openly and robustly debate issues relating to the etiology, epidemiology, treatment, prevention strategies, and public health consequences associated with the plague. Wu included in these activities the main rising power at the time, the United States, and Qing China’s rival, Japan. Official openness to international cooperation under Wu, despite the underlying tensions related to imperialism, facilitated greater collaboration and built international trust. These policies laid the groundwork for international cooperation during later epidemics in China during the 1920s, where foreign governments came generously to Wu’s assistance to keep these diseases under control.

Wu’s confidence and openness in dealing with major health crises are characteristics Chinese authorities today can and should emulate. Transnational challenges such as diseases require transnational solutions. Viruses, bacteria, and vectors know no political boundaries, national or otherwise. Chinese health authorities made the right call in sharing the genetic information regarding COVID-19 from Wuhan. This enabled scientists and doctors worldwide to work concurrently on detection, treatment, and vaccines. However, addressing public health concerns involves more than science alone. They require effective human and organizational responses as well. Here is where Beijing can take another leaf from Wu’s book.

Much has been made public about the initial suppression of information surrounding the initial outbreak of the coronavirus, which delayed official responses and public awareness that could have helped contain the disease. The widespread Chinese mourning of the death of Dr. Li Wenliang — a whistleblower who was investigated by local authorities early on for sharing news of the outbreak of the coronavirus — suggests that the government could do better in addressing potential long-term public health concerns. Just as important is learning about how human interaction with a changing natural environment and complex social contexts affects the spread of disease. How state, societal, and individual responses to crises and complicated information affect disease demands more study to develop mitigation efforts. Precise knowledge about how public health crises shape public trust, governance, and the economy is lacking as well. To meet these concerns effectively, information on public health — and not just medicine and science — is key.

For all the ambitious talk about the “China Dream,” authorities in Beijing may find higher standards of transparency and inclusiveness difficult to attain. The Chinese government currently excludes Taiwan from the World Health Organization (WHO) and allegedly pressured the WHO to limit negative reporting on the coronavirus — all this during an ongoing emergency. Such action creates risky lacunae in state and societal responses to public health crises, which may be increasingly common globally due to climate change and increased human-animal contact. Before COVID-19, China experienced a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2002-3. It left about 800 people dead worldwide and thousands ill. Chinese health authorities have been battling African Swine Flu nation-wide since 2018 and a new Avian Flu outbreak in Hunan province, next door to the coronavirus-hit Hubei.

Under such circumstances, more access by and cooperation among health authorities globally are beneficial to the overall public good. Domestic as well as foreign donations of medical supplies and the sharing of scientific data cannot supplant information on public health responses, social systems, and cooperative on-the-ground investigation alongside international experts. Allowing non-partisan Chinese health experts to freely participate in discussion about the virus in and outside of China can allow the Chinese government to demonstrate its anti-epidemic measures more organically to a wider audience. Such efforts at increasing knowledge and common understanding could potentially mitigate levels of racism, xenophobia, and other forms of discrimination, which the world is unfortunately witnessing at present. Managing these broader issues goes beyond the accumulation and distribution of masks, suits, and other physical resources.

Looking again at the best practices Wu Lien-teh laid down all those years ago means that Beijing should consider embracing outside expertise and assistance as well as the sharing of its extensive public health and social data. They can tap local, regional, and global experts who managed epidemics such as SARS and Ebola — after all, it was only when Chinese authorities permitted doctors with SARS experience to speak on COVID-19 that there was some soothing of public worries. Allowing Taiwan to become an World Health Assembly observer, as China once did, can demonstrate China’s openness to set aside political differences to fight a global threat. Allowing more CDC scientists from the United States to visit China will demonstrate much needed global cooperation to combat the spread of the virus. When the current health crisis abates somewhat, the Chinese government can facilitate universal access and study of the disease and its spread — including the convening of international conferences as with the Manchurian Plague. Such steps can improve trust in the Chinese healthcare system and enhance the handling of serious challenges that will likely recur.

Wayne Soon is Assistant Professor of History at Vassar College and author of Global Medicine in China: A Diasporic History (Stanford University Press, Forthcoming).

Ja Ian Chong is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore and a 2019-2020 Harvard-Yenching Institute Visiting Scholar. He is author of External Intervention and the Politics of State Formation: China, Indonesia, Thailand—1893-1952 (Cambridge, 2012).

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of their institutions.