The remote Himalayan region of Ladakh, a union territory of India, has recently been in the news due to fighting between Indian and Chinese forces along disputed border with China’s Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR).

The immediate cause of the dispute is the lack of a clear border in the area. Before the colonial period, clear linear borders did not exist in the Himalayas because states conceptualized sovereignty differently, and because it was difficult and pointless to clearly delineate borders in sparsely populated high altitude areas. Even in colonial times, the difficulty of establishing a border between British India and the Qing Empire is demonstrated by the existence of several different British lines, none of which provided a final answer as to where the border between Ladakh and Tibet lay. Strategic, not historical, considerations were used to propose several lines: the Ardagh-Johnson line of 1865, which pushed the border up the most to the north and east, the more conservative Macartney–MacDonald Line of 1899, and a third line that was never seriously considered because it would have drawn the boundary along the Karakoram range to the south of the effective border, giving up parts of Ladakh.

Yet, regardless of where the existing boundary comes to lie, it would have kept Ladakh and Tibet apart: It would have merely formalized the fact that while Tibet lay in the Chinese sphere-of-influence, Ladakh would be associated with the political world of the Indian subcontinent. Despite their common history, religious heritage, and culture, how and why did Tibet and Ladakh come to be politically distinct? In fact, some of the western areas of the Tibetan plateau — Baltistan, part of the Pakistani region of Gilgit-Baltistan, the Indian union territory of Ladakh, as well as the Indian districts of Kinnaur and Lahaul and Spiti in Himachal Pradesh and the Nelong Valley of Uttarakhand— — were never truly ruled by the central Tibetan government, or a Chinese suzerin of Tibet.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

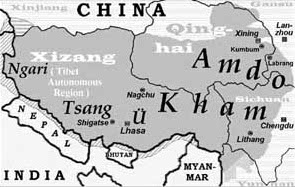

The Tibetan plateau — the geographic and cultural region associated with Tibet — has traditionally been divided into four historical regions. Three are almost entirely in China: Amdo in the north, now associated mostly with Qinghai and Gansu provinces in China, Kham in the east, split between Sichuan province and TAR, and Ü-Tsang, or central Tibet, the region is generally identified with the idea of Tibet, both culturally and administratively, although parts of Ü-Tsang extend to northern Nepal and the Indian states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. The fourth region, Ngari, is partially in China, where there is a Ngari prefecture in western Tibet, but much of the historical Ngari region is now in India. The most remote from the rest of Tibet, Ngari’s average elevation is 15,000 feet (4,500 meters). Its proximity to the Indo-Ganges plains has always opened it to Indian influences to a greater extent than the rest of Tibet: several prominent Hindu and Buddhist sites, such as Mount Kailash, where the Hindu god Shiva is said to reside, are located in Ngari.

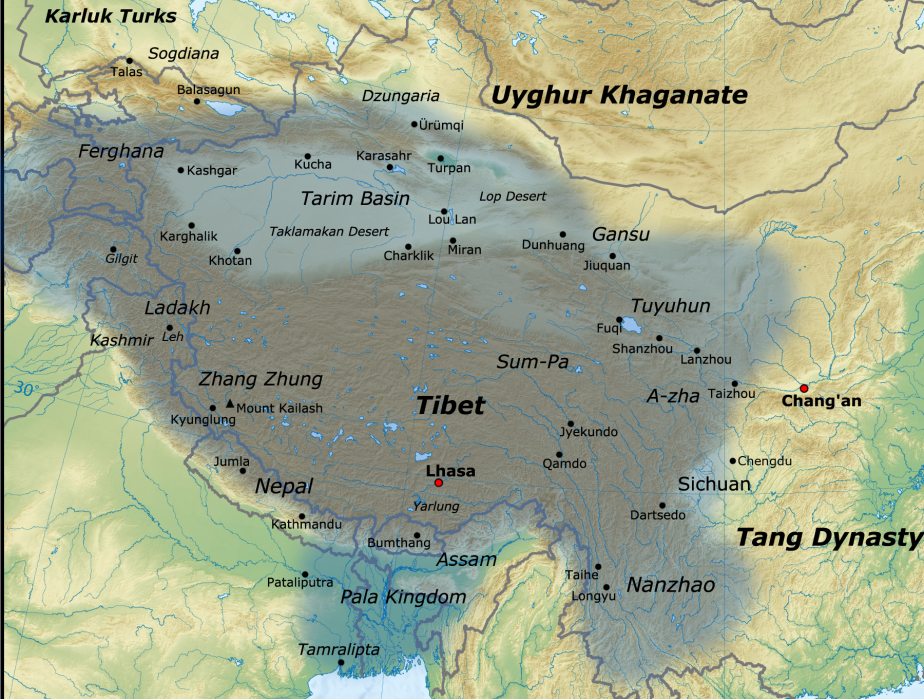

The Tibetans and Tibetan language form a part of the larger Sino-Tibetan language family which includes the Chinese languages and Burmese. The Tibetans are thought to have entered the Tibetan plateau around 3,000 years ago from the east. But ancient Tibetan records indicate that there were already people living in the western part of the plateau, called the Zhang Zhung, who practiced a pre-Buddhist religion, Bon. The Zhang Zhung capital Kyunglung was located on the Sutlej River near Mount Kailash, near the current border between China and India.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

It is unclear what language or culture the Zhangzhung spoke, or were part of, although some scholars believe the Kinnauri of Himachal Pradesh may be their descendants. The Zhang Zhung were incorporated into the Tibetan Empire, which lasted from the 7th to 9th centuries CE, and the area became culturally similar to the rest of Tibet, but the political unity of Tibet was short-lived. However, during this time, Tibetan Buddhism spread throughout the region, becoming a uniting factor for the various Tibetan successor states.

Much of what used to be the core of the Zhang Zhung culture broke away from the collapsing Tibetan Empire in the 10th century, led by a prince of the old state, Kyide Nyimagon, who subsequently divided his kingdom into three parts, Zanskar, Maryul, and Guge, the territories of which are partially now in India.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

While the culture of Zhang Zhung was displaced by Tibetan culture in these successor kingdoms, they remained distinct from the rest of Tibet in many ways. During the next few centuries, the rest of Tibet was caught up in the politics of East and Central Asia, with various Chinese and Mongolian dynasties attempting to exercise overlordship. Central Tibet eventually came to be ruled from Lhasa by the spiritual leaders of the Gelug (Yellow Hat) school of Tibetan Buddhism; the title of the ruler of Tibet, Dalai Lama, was bestowed by a Mongol leader, Atlan Khan, in 1578. However, the history of the western part of the Tibetan plateau, the Ngari region, especially those of the Guge and Maryul kingdoms, took a different route.

Maryul, which evolved into today’s Ladakh, was the strongest of the three western kingdoms. It brought Zanskar — today located in Ladakh Union Territory, and famously the home of Kargil, site of the Indo-Pakistani war of 1999 — under its control, eventually annexing it in the 17th century, giving it a border with Kashmir. However, even before this, there was a powerful Kashmiri influence on Ladakh — for example, Hindu tantric deities began to be worshiped throughout the Tibetan plateau by way of Ladakh — and there were several Kashmiri invasions of Ladakh in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Under a ruler named Lhachen Utpala (ruled 1080-1110 CE), Ladakh also became the overlord of neighboring Guge, which in turn controlled territory throughout today’s northern Himachal Pradesh and Nepal. Therefore, by the 12th century, Ladakh controlled directly or indirectly most of the territory along what is today the northwestern border between India and China.

The Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (1679-1684)

In 1460, a new, energetic dynasty, the Namgyal dynasty, began to rule Ladakh from Leh, and soon most of the rest of Tibet came to be ruled by the Dalai Lamas with Mongol backing. This Tibetan state — a theocracy — expanded southward, and propagated the Gelug sect.

Meanwhile, in Ladakh, Jamyang Namgyal (ruled 1595-1616) brought Baltistan (in today’s Pakistan) under his control, and Sengge Namgyal (lived 1570–1642) conquered Zanskar in 1638 and asserted overlordship over Guge; more importantly, he patronized a rival school of Tibetan Buddhism, the Drukpa (Red Hat) sect, which had been founded by an Indian sage from Bihar or Bengal, Naropa, in the 10th century.

The Drukpa school became a rallying point for resistance by various Tibetan statelets against Lhasa’s expanding control. In 1679, Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal consecrated a Drukpa state in the southern Himalayas that eventually became known as Bhutan. The neighboring kingdom of Sikkim also began to be ruled by a Namgyal from a different branch of the family. Tibet, having failed to subdue Bhutan, invaded Ladakh as punishment for its support of Bhutan in 1679 under the leadership of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

By this time, Ladakh had acknowledged the overlordship of the Mughal Empire, which had annexed neighboring Kashmir in 1586. Deldan Namgyal, and his son, Delek Namgyal (whose rule began in 1666) paid tribute to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and built a mosque in Leh, and parts of Ladakh became Muslim. While the Tibetans attempted to overrun all of Ladakh, they could not do so due to the support of the Mughal Empire, which saved the existence of an independent Ladakh, although the Tibetans prevailed in many ways. The key Treaty of Tingmosgang of 1684 between Tibet and Ladakh — which predates any agreement made by the British or Qing empires — acknowledged Ladakh’s independence from Tibet, but ceded much of the erstwhile Guge to Tibet, and allowed monks from the Gelug sect to practice and preach in Ladakh.

Nonetheless, the treaty and related agreements left most of what had been Maryul and Zanskar in Ladakh, and established a boundary that bisected the Pangong Tso (Lake), which is currently being disputed by Chinese and Indian forces. Further south, the treaty fixed the border of the two states at the Lhari stream (Demchok River). The treaty furthermore provided for a Ladakhi enclave near Mount Kailash, known as Minsar; there were also several Bhutanese enclaves in this part of western Tibet. While no treaty deprived Ladakh and Bhutan of these enclaves, they were essentially disposed of them in the 1950s after Tibet’s incorporation into the People’s Republic of China. Until the successor state of Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, was incorporated into India in 1948, the people of Minsar paid taxes to the Maharaja of Kashmir. India still theoretically claims Minsar.

Thus, the contours of the border between modern Tibet and Ladakh were established from this time onward, although a Chinese reading of the treaty suggests that the word used to describe a boundary at Demchok also means “meeting place” in Tibetan.

In 1834, a declining Ladakhi state was annexed by the Sikh Empire, which had arisen to control Punjab and Kashmir following the decline of the Mughal Empire,by General Zorawar Singh in 1834. A subsequent Sikh invasion of Tibet was halted in 1842, and the old borders and obligations between Ladakh and Tibet were reaffirmed by the Treaty of Chushul, of which the Qing Empire, Tibet’s suzerain, was also a party to. Ladakh was administratively attached to Kashmir, and subsequently to the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir upon its inception in 1846. The Hindu Dogra Dynasty ruled Jammu and Kashmir under the aegis of the British Raj for the next century, during which, despite various tinkering, it maintained similar borders to those established in 1684.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

While Ladakh is clearly rooted in Tibetan culture, its heritage is also distinctly non-Tibetan, particularly because its political history is different, its language has become mutually unintelligible with Standard Tibetan, and because, like Bhutan, it is religiously distinct from the rest of Tibet, as the Dalai Lama is not revered as much as he among Tibetans. Ladakh and its people are a thing of their own and Ladakh’s distinct and unique identity is preserved, to a large extent, from its political disassociation from the rest of Tibet, and its union with India. Due to its orientation toward South Asia, and its clear history of demarcation from Tibet, it is not surprising that its people continue to wish to be distinct from Tibet and China.